Tamar Cham, Parts 1 and 2

Historical Records

Performance Records

Playlists in Philip Henslowe's diary

| Fol. 7 (Greg 1.13): | |||||

| ne . . . | Res at the second pte of tamber came the 28 of aprell . . . | iijll iiijs | |||

| Res at the 2 pte of tambercam ye 10 of maye 1592 . . . . . . . | xxxvijs | ||||

| Res at tambercam the [18] 26 of maye 1592 . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxvjs vjd | ||||

| Fol. 8r (Greg 1.15): | |||||

| Res at <the> tambercame the 8 of June 1592 . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxxs | ||||

| Res at tambercame the 21 of June 1592 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxijs | ||||

| Res at tambercam the 19 of Jenewarye 1593 . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxvjs | ||||

| Fol. 15v (Greg 1.30): | |||||

| ye 6 of maye 1596 | ne . . | Res at tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxxvijs | ||

| ye 12 of maye 159[5]6 | Res at tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxxvs | |||

| ye 17 of maye 1596 | Res at tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxxvjs | |||

| ye 25 of maye 1596 | Res at tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxs | |||

| Fol. 21v (Greg 1.42): | |||||

| ye 5 of June 1596 | Res at tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxviijs | |||

| ye 10 of June 1596 | Res at tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxviijs | |||

| ye 11 of June 1596 | ne . . | Res at the 2 pte of tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | iijll | ||

| ye 19 of June 1596 | mr pd | Res at 1 pte of tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxvjs | ||

| ye 20 of June 1596 | Res at 2 pte of tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxvs | |||

| ye 26 of June 1596 | Res at 1 pte of tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxxs | |||

| ye 27 of June 1596 | Res at 2 pte of tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxs | |||

| ye 8 of July 1596 | Res at 2 p of tamber came . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xxiijs | |||

| ye 8 of July 1596 | Res at j p of tamber came . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xiiijs | |||

| Fol. 25 (Greg 1.49): | |||||

| ye 13 of novmbƺ 1596 | Res at tambercame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | xvijs |

Payments

Purchase of the play from Edward Alleyn in Philip Henslowe's diary

Fol. 108 (Greg 1.171)

pd vnto my sonne E. Alleyn at the a poynt } ment of the company [of the] for his Boocke } xxxxs of tambercam the 2 of octobƺ 1602 the some of }

Fol. 116v (Greg 1.182)

pd vnto my sonne E Alleyn at the a } poyntment of the company for his } xxxxs Boocke of tambercam the 2 of octobƺ } 1602 the some of }

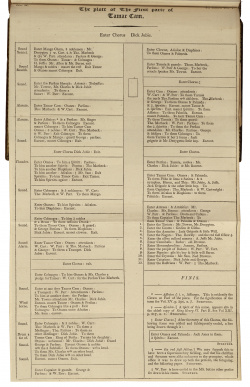

Plot for "1 Tamar Cam" (Admiral's, 1602)

This plot, for a revival of Part 1 by the Admiral's Men in 1602, was transcribed by Steevens and printed by Isaac Reed in the "Variorum" Shakespeare of 1803; the original has since disappeared. Only the published transcription survives. Steevens' version of the plot does not appear to have been digitised currently, and most scholars rely on Greg's reprinting (from Henslowe Papers 145-48 (Internet Archive)), which does not preserve the layout. Here is Steevens' edition, courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library:

“The Plotte of the First Parte of the Tamar Cam”, The plays of William Shakspeare : in twenty-one volumes : with the corrections and illustrations of various commentators, to which are added notes / by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. 1803. Foldout after leaf 2D8 verso (page 414). Folger PR2752 1803a v.3 copy 1 Sh.Col. Reproduced by permission.

Theatrical Provenance

Initially produced by Strange's, with Part 2 being performed on 28 April 1592 (marked "ne" by Henslowe). The plays were acquired by the Admiral's by 1596, when Part 1 was revived on 06 May and Part 2 on 11 June. The Admiral's bought the book of the plays from Alleyn in 1602. Greg (Dramatic Documents, p. 161) notes the absence of Jones and Shaa (indicating performance after January 1602) and the presence of Singer (indicating a date of before 1603, when he left the company).

Probable Genre(s)

Tragedy; Eastern conqueror.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

See Critical Commentary below for scholars' opinions on possible story lines.

References to the Play

In Dekker's The Shoemaker's Holiday (1600), Simon Eyre refers to Tamar Cham's beard:

- Eyre. My liege, a very boy, a stripling, a younker. You see not a white hair on my head, not a grey in this beard. Every hair, I assure thy Majesty, that sticks in this beard Sim Eyre values at the King of Babylon's ransom. Tamar Cham's beard was a rubbing-brush to't. Yet I'll shave it off and stuff tennis balls with it to please my bully King. (XXI.20-25)

In their gloss to this line, the Revels editors suggest that "[p]erhaps something special was made of the hero's beard" in the lost "Tamar Cham" plays, and further note the recurrence of beard imagery in Much Ado, when Benedick offers to fetch "a hair off the great Cham's beard" (II.i.237-8).

In Timber: or, Discoveries, Jonson complained of "the Tamerlanes, and Tamer-Chams of the late Age, which had nothing in them but the scenicall strutting, and furious vociferation, to warrant them to the ignorant gapers" (H&S 8.587).

Wiggins, Catalogue (#906) cites allusions in Blurt, Master Constable and Wily Beguiled, also possibly in Jonson's Poetaster and Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida. Based on these allusions, Wiggins deduces that the character of Mango was fat and the character of Assinico/Asinico was stupid.

Critical Commentary

Malone annotates the title as "Tamburlane" (p. 292). Collier, rarely shy about calling out Malone's perceived errors, notes the misspelling of Tamburlaine; significantly, however, he rejects the identification with Marlowe's play in large part because he trusts Henslowe's apparently marking of this second part as new. He reads the entry as an offering "on the same story" as Marlowe's, but he hedges his bet by noting that the two-part Tamburlaine had belonged to the Admiral's men "with whom Henslowe was certainly connected" (p. 25, n.3). Fleay, BCED (2.298 #115) grants the "Tamar Cham" plays an independent identity.

Greg II also considers the pair a rival to Marlowe's Tamburlaine, and he emphasizes its commercial value by discussing the revival of one or both parts when it migrated to the Admiral's men. In 1931 he suggests a possible story line: "[i]f the play was written as a rival to Tamburlaine, what more effective counterblast could there be than one celebrating the exploits of the far greater conqueror Jenghis Khan? The suggestion tallies well with the prominence given to the Persian Shah, who would in that case be Mahommed of Khwarizm, and the procession of subject races at the end of Part I would be entirely appropriate; while the Second Part might be supposed to have celebrated the Mongol successes in Russia and China. It is possible that the unknown author boldly altered the name of his hero to one more familiar to his audience, but it is also conceivable that he knew that Jenghis Khan is properly an honorific and that his real name was Temuchin, and made this an excuse for giving his play a title closely similar to that of the piece he sought to rival" (Dramatic Documents, pp. 161-2).

McInnis suggests on the basis of the plot that "1 Tamar Cham" "had as much in common with the fantastical and magical elements of Faustus as it had an affinity with the Tamburlaine phenomenon", judging by the procession of distinctly exotic characters at the end of the play: "The participants in this procession belong more to Mandevillian fantasy than chronicle history; their prominence in the denouement of the play suggesting that the allure of the exotic was (for the audiences of ‘1 Tamar Cham’) as much of a draw as the adoption of subject matter overtly reminiscent of Marlowe’s hugely successful conqueror plays" (pp. 71-72).

Manley and Maclean conjecture at length about the likely content of the second part in particular:

- Perhaps appropriately described as a 'spin-off of the elder Tamburlaine plays,' 'tambercame' appears to have been about an exotic, anti- Muslim scourge, and like The Battle of Alcazar, which featured 'a Portingale' as a choric narrator to relate to the audience the 'strange but true' history of the battle of the three kings at El- Ksar Kbir, 'The plot of The first parte of Tamar Cam' featured Dick Jubie as a 'Chorus' and probable narrator of the play’s unfamiliar story. Because there is no surviving plot for 'the second parte of tamber came,' it is more difficult to say where the sequel might have ended, but there was ample material for a follow-up in Tamar Cam’s (i.e., Hülegü’s) subsequent conquests of Baghdad and Aleppo, his wife’s mercy on the Christians of Baghdad, the death of the fourth emperor 'Mango Cam,' Tamar Cam’s return to the East, and the reversal of Tamar Cam’s victories when his successor became the victim of Christian treachery.133 These events would yield a sequel not unlike the second part of Tamburlaine, where the entropic forces of death and a failed succession overtake earlier triumphs. (pp. 142-43; see also n.131, n.132, and n.133)

Wiggins, Catalogue (#906 and #925) guesses that part one existed some time in 1591, possibly after Edward Alleyn joined Lord Strange's men in May. He offers the further possibility that "The Tamar Cham plays could have been an attempt to create a comparable vehicle [to the Tamburlaine plays] for Lord Strange's Men's new star turn" (#906).

For What It's Worth

How reliable is the transcription? Noting that Reed also printed the plots of "The Dead Man's Fortune" and of "Frederick and Basilea" (the originals of both of which survive, facilitating comparison with the transcriptions), Greg, in Dramatic Documents, observes that in Steevens’ work habits, although "small differences of spelling are numerous, more serious lapses are comparatively rare": for example, Steevens transcribes "sir" for "hir", "goliors" for "soliors", "enters" for "Enter", and "servants" for "seruant", apparently (Greg notes) "to suit what he erroneously supposed to be the sense required". More alarmingly, however, Steevens also "transferred marginal additions to the text, and printed deletions as though they stood". This accumulation of minor but not insignificant variation between primary document and transcription led Greg to suppose that in the case of "Tamar Cham", Steevens "may be generally trusted as regards the main features of the Plot, [but] considerable caution is needed in making inferences from points of detail" (p. 160).

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated 08 August 2018.

- Folger

- Edmond Malone

- F. G. Fleay

- All

- David McInnis

- Strange's

- Admiral's

- Henslowe's records

- Edward Alleyn

- Eastern

- Travel

- Plots and arguments

- Serial/Sequel plays

- Plays

- Richard Juby (Dick)

- Thomas Downton

- William Parr

- Thomas Towne

- Robert Shaw (Shaa)

- Thomas Marbeck

- Thomas Parsons

- John Singer

- Jack Gregory

- Will Barne

- Samuel Rowley

- Charles Massey