Friar Rush and the Proud Woman of Antwerp

Henry Chettle, John Day, William Haughton (1602)

Historical Records

Payments to Playwrights (Henslowe’s Diary)

Henslowe's records of the play's composition between July 1601 and January 1602 indicate a gradual emphasis on the "Proud Woman" at the possible expense of "Friar Rush":

- Lent vnto John daye and wm hawghton at the

- a poyntmente of Robert shawe in earnest of a

- Boocke called fryer Rushe & the prowde womon

- the some of the 4 day of July ..... xxs

- (F.91, Greg I.143)

- Lent vnto Robert shawe the 14 of July

- 1601 to geue vnto wm hawghton & John daye

- in earneste of a Boocke called the prowde

- womon of anwarpe ^ frier Rushe the some of ..... xxxs

- (F.91v, Greg I.144)

- dd vnto wm hawghton at the apoyntment

- of Samwell Rowlley the 31 of septmbr 1601

- pt of payment of a Boocke called the prowde

- woman of anwarpe the some of ..... xs

- (F.94, Greg I.149)

- Lent vnto Samwell Rowley by the apoyntment

- of the companye the 9of novmbr 1601 to paye vnto

- wm hawghton for his boocke of the prowd

- womon of anwarppe the some of ..... xxs

- (F.94v, Greg I.150)

- Lent vnto Samwell Rowlley the 29 of nvmbr

- 1601 to paye wm hawghton in full paye for his

- playe called the prowd womon of anwarp the

- some of ..... xxs

- (F.95, Greg I.151)

- Lent vnto Robert shawe the 21 of

- Janewary [1602] to geue vnto harey

- cheattell for mendinge of the Boocke

- called the prowde womon the some of ..... xs

- (F.104, Greg I.164)

Theatrical Provenance

Henslowe commissioned the play for the Admiral's Men at the recently built Fortune playhouse.

Probable Genre(s)

Comedy (?)

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

Friar Rush

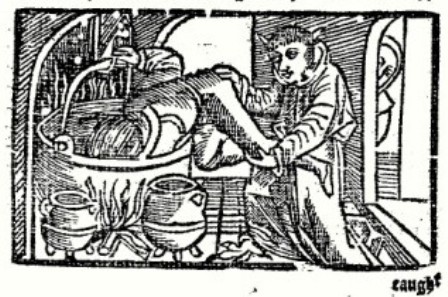

- Detail from The Historie of Frier Rush (1626 ed, A4v)

“Bruder Rausch” was a popular late medieval trickster of Low German folklore (Herford 293-322).

A “boke intituled ffreere Russhe” was entered into the Stationers’ Register in 1568-69 (Arber 1. 389) but does not survive.

The most complete extant treatment of the character in English is the prose jest-book The Historie of Frier Rush (1620), which collects several episodes possibly adapted to the stage.

In this account, an infernal council led by Belphegor, Asmodeus, and Beelzebub enlists an eager devil to put on “rayment like an earthly creature” and sow “debate and strife among the Friers” of a continental monastery (Historie A2v-A3r). Disguised as a young acolyte named Rush, the devil is appointed to serve as a scullion and proceeds to wreak havoc. He entices a local gentlewoman to make “good cheere” in the Prior’s bedchamber (A3v-A4v). He throws the master cook into the kitchen’s “great kettell … full of water seething vpon the fire,” deeming it a suicide (A4v-Br). He becomes the new master cook and feeds the Friars bacon on Lent (Bv). When the brethren invite him to wear the habit, Rush introduces oak truncheons to the house, ostensibly to ward off thieves. The friars quickly descend to bludgeoning each other in the choir, giving him the opportunity to blow out all the candles and bring an “old Deske” crashing down on the them “in so much that some had an arm broken, and some a legge, and other some had their noses clean pared from their faces” (Bv-B3v). Other antics follow: the seat of the Prior’s wagon is greased with tar and the horses treated to wine (B3v-B4v); a set of stairs are removed and the light extinguished so that the friars fall down on top of each other in the dark (Cr-C2v); a cow is neatly divided in two to produce an instant feast (C2v-C3r). When the owner of the bisected cow has a vision in a hollow tree that reveals Rush’s true identity and reports the news to the Prior, the contrite brethren compel Rush to depart in the shape of a horse (C3v-D2v). Wandering the countryside in search of mischief, Rush participates in a fabliau involving a a poor farmer, his brawling wife, and a lascivious priest (D3r-E2v). Finally, he enters the service of a gentleman disturbed by the demonic possession of his daughter. Rush invites the gentleman to summon his old master, the Prior, who arrives, blesses the woman, and releases a great devil out of her mouth. In return for his assistance, the gentleman grants the Prior an enormous load of lead for the roof of a new church. The narrative concludes with the Prior calling upon Rush “to take on his neck so much lead as would couer his Church,and bear it home” and then to take the Prior on his neck and convey him home as well (E3r-E3v).

The Proud Woman of Antwerp

The 1584 edition of Philip Stubbes’s Anatomie of Abuses relates a “fearfull example against pride shewed vpon a gentlewoman in Antwarpe.” This “true” event reportedly occured on 27 May 1582 and is described as knowledge that has “blowne through all the worlde, and is yet in euery mans memory”:

This gentlewoman being a very rich Marchaunte mannes daughter vpon a time was inuited to a Bridall, or Wedding, whiche was solemnized in that Towne, agaynst which day shee made great preparation, for the pluming of her selfe in gorgeous arraie, that as her bodye was moste beautifull, fayre, and proper, so her attire in euery respecte might be correspondent to the same. For the accomplishment whereof shee curled her haire, she died her lockes, and layed them out after the best maner, she coloured her face with waters and Ointmentes: But in no case could she gette any (so curious and daintie she was) that could starche and set her Ruffes and Neckerchers to her mind: wherefore shee sent for a couple of Laundresses, who did the best they could to please her humors, but in any wise thei could not: Then fell shee to sweare and teare, to cursse and baune, casting the Ruffes vnder feete, & wishing that the Deuill might take her when she [might wear] any of those Neckerchers agayne. In the meane time (through the sufferaunce of God) the Deuill transforming himselfe, into the forme of [a] younge man, as braue, and proper as shee in euerie poincte in outward appeareaunce, came in, fayning himselfe to bee a woer or suter vnto her. And seeing her thus agonized, and in such a pelting chafe, he demaunded of her the cause thereof who straight-waye tolde him (as women can conceale nothing that lyeth vppon their stomackes) howe shee was abused in the setting of her Ruffes, which thing being hearde of him, hee promised to please her minde, and thereto tooke in hand the setting of her Ruffes, which he peformed to her great contentation, and liking, in so muche as shee looking herselfe in a glasse (as the Deuill bad her) became greatly inamoured with him. This done, the young man kissed her, in the doing wherof, he writhe[d] her necke in sonder, so she dyed miserably , her body being Metamorphosed, into blew and black colours, most vgglesome to behold, and her face (whiche before was so amorous) became moste deformed, and fearefull to looke vpon. This being known preparaunce was made for her burial, a rich Coffin was prouided, and her fearefull body was layed therin, and it couered very sumptuously. Foure men immediately assaied to lift vp the corpes, but could not moue it, then sixe attempted the lyke, but could not once stirre it from the place where it stoode. Whereat the standers by marueiling, caused the Coffin to be opened, to see the cause therof. Where they found the body to be taken away, and a blacke Catte very leane and deformed sitting in the Coffin, setting of great Ruffes, and frizling of haire, to the great feare, and wonder of all the beholders. This woefull spectacle haue I offered to their viewe, that by looking into it, in stead of their other looking Glasses they might see their owne filthinesse & auoyd the like offence, for feare of the same, or worser iudgment: whiche God graunt they may doe. (38)

References to the Play

Friar Rush

An allusion in Gammer Gurton’s Needle indicates Friar Rush had entered English popular culture by the mid-sixteenth century. In 3.2, Hodge likens the beggar Diccon to a devil:

- … saw ye neuer Fryer Rushe

- Painted on a cloth, with a side long cowes tayle:

- And crooked clouen feete and many a hoked nayle?

- For al the world (if I shuld iudg) chould recken him his brother

- Loke euen what face Frier Rush had, the deuil had such another (Ciiv)

Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) suggests the character was seen largely as a figure of fantasy, the fables of “Frier Rush, Adam Bell, or the golden Legend” being too “grosse and palpable” to merit refutation (498).

Dekker’s If This Be Not a Good Play the Devil is in It (1610) features a version of Friar Rush and expands upon his tale's premise by dramatizing the intrusion of three devils into religious, urban, and courtly environments.

The plot of Jonson’s The Devil is an Ass (1616) also echoes the basic scenario of the Rush legend.

The Proud Woman of Antwerp

There may be a passing allusion to the "Proud Woman" in Greene's Tu Quoque by Cooke (1614). When the character Longfield in that play declares his love for Will Rash's sister, Rash remarks: "for pride,the woman who had her Ruffe poak'd by the diuell is but a Puritan to her" (Cv).

Similarly, among the ballads Nightingale advertises in Jonson's Bartholomew Fair 2.4 (1614) is one called "Goose-greene-starch and the Deuill" (22)

Critical Commentary

A play entitled "The Godly Woman of Antwerp" was acted by John Greene and Robert Browne’s traveling English company in Graz in 1608. Given the ties of these players to the Admiral's Men, this may refer to a version of Day and Haughton’s play (Morris 18).

Morris includes a detailed transcription of the letter, which describes the play as "von einer frommen frauen von antorf". Earlier sources, such as Sibley (198), slightly mangle the title from the 1608 record, giving it as "Die fromme frau zu Antorf". The suggestion that it could be identified with Day and Haughton's play goes back beyond Sibley.

For What It's Worth

The backgrounds of these titular characters suggests a moral comedy with perhaps a festive or grotesque tone.

Twenty-two years later, the Admiral's Men (now the Palsgrave's Men) licensed another play about a woman from Antwerp, possibly dramatizing the same story again: see The Fair Star of Antwerp.

Another possible allusion to the play, or at least to the underlying story, in 1615:

- O Earth, thinke on the fearfull Iudgement shewed on a woman in Antwerpe (as it is related) to whome the diuell appeared to set her Ruffs, which when he had finished, he kissed her, & wroong her necke in twoo. Her bodie suddenly changed blacke and blewe, painted and coloured small to her profite. Laid in a toumbe, she was suddenly gone, and a blacke deformed Cat in the roome. If curious Ruff-mongers, be incredu|lous of this, I wish them beware, least to them come the like.

- B. H., The glasse of mans folly and meanes to amendment, for the health and wealth of soule and body (London: I.H[arrison], 1615), 28. This passage is among material added in the 1615 edition, and not present in an earlier edition of 1595.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Christopher Matusiak, Ithaca College; updated 5 July 2011. Additions by Matthew Steggle, Sheffield Hallam University, July 2016.