Oldcastle, Sir John (Chamberlain's): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (16 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==Historical Records== | ==Historical Records== | ||

=== | ===Correspondence=== | ||

'''8 March 1599/1600: Letter from Rowland Whyte to Sir Robert Sidney''' <br> | '''8 March 1599/1600: Letter from Rowland Whyte to Sir Robert Sidney''' <br> | ||

Whyte provides details of a dinner given on 6 March 1600 by the Lord Chamberlain (George Carey) during the visit by Louis Verreyken, a diplomat in the service of Archduke Albert (Collins, II. 174-6; esp. 175-6): | Whyte provides details of a dinner given on 6 March 1600 by the Lord Chamberlain (George Carey) during the visit by Louis Verreyken, a diplomat in the service of Archduke Albert (Collins, II. 174-6; esp. 175-6): | ||

:"All this Weeke the Lords haue bene in ''London'', and past away the Tyme in Feasting and Plaies; for ''Vereiken'' dined on ''Wednesday'', with my Lord ''Treasurer'', who made hym a Roiall Dinner; vpon ''Thursday'' my Lord Chamberlain feasted hym, and made hym very great, and a delicate Dinner, and there in the After Noone his Plaiers acted, before ''Vereiken'', Sir ''John Old Castell'', to his great Contentment. This Day the Lords are going to Court. My Lord ''Harbert'' wil be here vpon ''Wednesday'', he must be the honorable Instrument of much good to your Lordship, and I find your Lordship wilbe thoroughly delt withall vpon your Return, by 600 [i.e., the Earl of Nottingham] in the Matter I soe often mentioned vnto you; if yt bring you Honor, and Contentment to all Parties, I shall thinke my self happy to haue bene the first Motioner of yt." (signed "''Baynards'' Castell, this ''Saturday'', 8 of ''March'' 1599") | |||

Collins's edition, characteristically, omits some of the original letter. After "This Day the Lords are going to Court" and before "My Lord ''Harbert''..." Whyte wrote some more sentences of news for Sidney, but nothing relevant to the performance (Brennan, Kinnamon, and Hannay, 439). | Collins's edition, characteristically, omits some of the original letter. After "This Day the Lords are going to Court" and before "My Lord ''Harbert''...," Whyte wrote some more sentences of news for Sidney, but nothing relevant to the performance (Brennan, Kinnamon, and Hannay, p. 439). | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

=== | ===Government Documents === | ||

'''Warrant for payment from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office to Sir William Uvedale, Treasurer of the Chamber, with a list of plays performed before the King and Queen [manuscript], 1630/1 March 12:'''<br> | '''Warrant for payment from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office to Sir William Uvedale, Treasurer of the Chamber, with a list of plays performed before the King and Queen [manuscript], 1630/1 March 12:'''<br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br>[[category:Folger]] | <br>[[category:Folger]] | ||

====Dramatic Records of Sir Henry Herbert==== | |||

'''Henry Herbert, Court Plays acted by the King's Men, 1638-9''' | '''Henry Herbert, Court Plays acted by the King's Men, 1638-9''' | ||

| Line 46: | Line 48: | ||

==Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues== | ==Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues== | ||

John Foxe describes the execution of Sir John Oldcastle in Lincoln's Inn Fields in 1419 ([http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/johnfoxe/main/2_1563_0277.jsp ''Actes and Monuments ...'' or ''Booke of Martyrs'']).<br> | :John Foxe describes the execution of Sir John Oldcastle in Lincoln's Inn Fields in 1419 ([http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/johnfoxe/main/2_1563_0277.jsp ''Actes and Monuments ...'' or ''Booke of Martyrs'']). | ||

<br> | |||

:The [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/20674 Oxford DNB] includes the life of Oldcastle. | |||

<br> | |||

:In October 1599, the Admiral's Men purchased part one of a play on the life of Sir John Oldcastle from Anthony Munday, Michael Drayton, Robert Wilson, and Richard Hathway; they paid additional moneys in earnest on "[[Sir John Oldcastle, Part 2 |the second part]]". In early November Munday and his collaborators were given 10s. on the performance of the play for the first time. The first part of the Admiral's play was printed in 1600, advertising itself as a first part on the title page. Sometime between 19 and 28 December, Michael Drayton was paid 80s. for the rest of the second half. The company laid out 30s. "to macke thinges" for the second part, which presumably was then staged. It is now lost. | |||

<br> | |||

In October 1599, the Admiral's Men purchased | |||

:In August 1602 Worcester's Men paid Thomas Dekker 40s. plus another 10s. in September for "new a dicyons" to "Oldcastle" ([[WorksCited|Greg, I.179, 181)]]. In addition the company bought apparel for the production including "a sewt for owld castell" ([[WorksCited|Greg, I.179]]). <br>[[category:Costumes]] | |||

<br> | |||

The relationship of these plays for the Admiral's Men and Worcester's Men to the play given by the Chamberlain's Men in March 1600 at the London residence of their patron is unclear, but the general biographical matter of the title character must have been shared. | :The relationship of these plays for the Admiral's Men and Worcester's Men to the play given by the Chamberlain's Men in March 1600 at the London residence of their patron is unclear, but the general biographical matter of the title character must have been shared. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 66: | ||

==References to the Play== | ==References to the Play== | ||

References to a discrete play called "Oldcastle" in the repertory of the Chamberlain's Men are complicated | References to a discrete play called "Oldcastle" in the repertory of the Chamberlain's Men are complicated. Historically, scholars have identified lost plays with extant ones; they have also identified lost plays with items in the Shakespeare canon. Consequently, the "Oldcastle" play discussed in Whyte's letter to Sidney has been identified with Shakespeare's ''1 Henry IV'' on evidence that Shakespeare initially named Prince Hal's tavern companion in that play "Oldcastle" but changed the name to "Falstaff" when the Cobham family allegedly objected (Lord Cobham was Lord Chamberlain, but not also the Chamberlain's company patron, for less than a year in 1596-7). Traces of the name change are in the printed texts of ''1 Henry IV'' (e.g., "my old lad of the castle" 1.2.41). In a Shakespeare-centric scholarly tradition, references to "Oldcastle" were interpreted as references to "Falstaff" and therefore to the extant Shakespearean first part of the Henriad. A feature of that Shakespeare-centric scholarly tradition was the belief that the Chamberlain's men would not have acquired a play on the same subject (and not have given it the same title) as a play in the repertory of another adult commercial company. | ||

The evidence most often cited that the Falstaff-Oldcastle name switch persisted in the company's collective memory is in ''Amends for Ladies'' (Q1618) by Nathan Field, a player and dramatist who joined the King's Men c. 1615. Field appears to link Falstaff and Oldcastle in the following line: "The Play where the fat Knight, hight Old-castle/ Did tell you truly what his honour was?" (iv.3) (as quoted by Chambers, I.382). | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

==Critical Commentary== | ==Critical Commentary== | ||

Chambers typifies the scholars of his time by reading Rowland Whyte's naming of a play called "John Old Castell" as a reference to Shakespeare's ''Henry IV, part 1'': "''Henry IV'' must have been the ''Sir John Old Castell'' with which the Lord Chamberlain entertained an ambassador on 8 March 1600, since the players were his men and not the Admiral's" (1.382). Chambers also reads the 1638 performance at the Cockpit as a performance of Shakespeare's ''Henry IV, part 1'' (i.382). | '''Chambers''' typifies the scholars of his time by reading Rowland Whyte's naming of a play called "John Old Castell" as a reference to Shakespeare's ''Henry IV, part 1'': "''Henry IV'' must have been the ''Sir John Old Castell'' with which the Lord Chamberlain entertained an ambassador on 8 March 1600, since the players were his men and not the Admiral's" (1.382). Chambers also reads the 1638 performance at the Cockpit as a performance of Shakespeare's ''Henry IV, part 1'' (i.382). | ||

'''McManaway''' continues that opinion in an essay for ''Shakespeare Quarterly'' in which he revisits a pair of documents held by the Folger Shakespeare Library. One is a warrant authorizing the playing companies to be paid (formerly Folger MS 2068.7, now X.d.110 (1)); the other is a schedule of four performances at Hampton Court and sixteen at the Cockpit playhouse (formerly Folger MS. 2068.8, now X.d.110 (2)). The schedule lists the plays given before Charles I from 30 September 1630 through 21 February 1631. Addressing the entry on 6 January of "Olde Castle," McManaway observes that the title "is surely not" the Admiral's play written by Drayton, Munday, Wilson and Hathway (121). Reciting the Whyte and Field references plus the 29 May 1638 performance as evidence of how hard it was "to efface the memory of the surname originally borne" by Shakespeare's Falstaff, he concludes that "even in Shakespeare's own company in the fourth decade after ''1'' and ''2 Henry IV'' were first performed his fellows thought of the play as ''Oldcastle''" (122). [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2866215 JSTOR] | '''McManaway''' continues that opinion in an essay for ''Shakespeare Quarterly'' in which he revisits a pair of documents held by the Folger Shakespeare Library. One is a warrant authorizing the playing companies to be paid (formerly Folger MS 2068.7, now X.d.110 (1)); the other is a schedule of four performances at Hampton Court and sixteen at the Cockpit playhouse (formerly Folger MS. 2068.8, now X.d.110 (2)). The schedule lists the plays given before Charles I from 30 September 1630 through 21 February 1631. Addressing the entry on 6 January of "Olde Castle," McManaway observes that the title "is surely not" the Admiral's play written by Drayton, Munday, Wilson and Hathway (p. 121). Reciting the Whyte and Field references plus the 29 May 1638 performance as evidence of how hard it was "to efface the memory of the surname originally borne" by Shakespeare's Falstaff, he concludes that "even in Shakespeare's own company in the fourth decade after ''1'' and ''2 Henry IV'' were first performed his fellows thought of the play as ''Oldcastle''" (p. 122). [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2866215 JSTOR] | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

'''Taylor''', who is defending the restoration of the name, "Oldcastle," for Falstaff in the Oxford edition of ''1 Henry IV'', characterizes the references to the Oldcastle play (above) as "considerable evidence" that ''1 Henry IV'' "was, even after 1597, sometimes privately performed with the original designation intact [of Falstaff as Oldcastle]" (90). Observing that "''Part 1'' was sometimes referred to as 'Falstaff', ... it should not surprise us if the uncensored version were identified as 'Oldcastle'" (90-1). Documenting the alternate title of "Falstaff" for ''1 Henry IV'', Taylor cites three instances in court records in 1613, 1635, and ''c''. 1619-20 (90n). [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2866215 JSTOR] | '''Taylor''', who is defending the restoration of the name, "Oldcastle," for Falstaff in the Oxford edition of ''1 Henry IV'', characterizes the references to the Oldcastle play (above) as "considerable evidence" that ''1 Henry IV'' "was, even after 1597, sometimes privately performed with the original designation intact [of Falstaff as Oldcastle]" (p. 90). Observing that "''Part 1'' was sometimes referred to as 'Falstaff', ... it should not surprise us if the uncensored version were identified as 'Oldcastle'" (pp. 90-1). Documenting the alternate title of "Falstaff" for ''1 Henry IV'', Taylor cites three instances in court records in 1613, 1635, and ''c''. 1619-20 (p. 90n). [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2866215 JSTOR] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''Dutton''' asks, "Was it Whyte or the players themselves, who kept alive the association between Oldcastle and Falstaff?" (106) In answer, he explores two contexts beyond the flap about the character's name: Edmond Tilney's allowing ''1 Henry IV'' to be licensed, even though it carried the Oldcastle name; and the possibility that, after the elder Lord Cobham died in 1597, his heir carried on the family's sense of injury (102-7). | '''Dutton''' asks, "Was it Whyte or the players themselves, who kept alive the association between Oldcastle and Falstaff?" (p. 106) In answer, he explores two contexts beyond the flap about the character's name: Edmond Tilney's allowing ''1 Henry IV'' to be licensed, even though it carried the Oldcastle name; and the possibility that, after the elder Lord Cobham died in 1597, his heir carried on the family's sense of injury (pp. 102-7). | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''Gurr''', in ''The Shakespearian Playing Companies'', marks ''Oldcastle'' "(lost?)" in a list of the Chamberlain's Men's plays (303); in ''The Shakespeare Company'', he appears to have changed his mind and links the Oldcastle performance at the Lord Chamberlain's house with Shakespeare's ''I Henry IV'' (170, 283). | '''Gurr''', in ''The Shakespearian Playing Companies'', marks ''Oldcastle'' "(lost?)" in a list of the Chamberlain's Men's plays (p. 303); in ''The Shakespeare Company'', he appears to have changed his mind and links the Oldcastle performance at the Lord Chamberlain's house with Shakespeare's ''I Henry IV'' (pp. 170, 283). | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''Kastan''' disputes the identity of the play given at Hunsdon House as the Admiral's ''Sir John Oldcastle'' but does not consider independently the possibility that the play was the one here represented as lost. In fact, he asserts that the Chamberlain's ''Oldcastle'' was "almost certainly Shakespeare's ''1 Henry IV''" (95). Beyond that, his argument is with Taylor's restoration of the Oldcastle name in the Oxford text of ''1H4'': "The restoration of 'Oldcastle' enacts a fantasy of unmediated authorship paradoxically mediated by the Oxford edition itself" (102). For the lost play, perhaps the most relevant piece of Kastan's argument is his exploration of the survival of the name "Falstaff" in seventeenth-century allusions (105). His crowning point is that Heminges and Condell could have restored the "Oldcastle" name under their claim to repair defective earlier quartos, but they did not (106). | '''Kastan''' disputes the identity of the play given at Hunsdon House as the Admiral's ''Sir John Oldcastle'' but does not consider independently the possibility that the play was the one here represented as lost. In fact, he asserts that the Chamberlain's ''Oldcastle'' was "almost certainly Shakespeare's ''1 Henry IV''" (p. 95). Beyond that, his argument is with Taylor's restoration of the Oldcastle name in the Oxford text of ''1H4'': "The restoration of 'Oldcastle' enacts a fantasy of unmediated authorship paradoxically mediated by the Oxford edition itself" (p. 102). For the lost play, perhaps the most relevant piece of Kastan's argument is his exploration of the survival of the name "Falstaff" in seventeenth-century allusions (p. 105). His crowning point is that Heminges and Condell could have restored the "Oldcastle" name under their claim to repair defective earlier quartos, but they did not (p. 106). | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''Marino''' is primarily concerned with how William Jaggard [[category:William Jaggard]] came to attribute the Admiral's play, ''Sir John Oldcastle'', to Shakespeare in the so-called ''Pavier Quartos''. He discusses the moment in 1599-1600 when the Admiral's play was new and the Chamberlain's men entertained their patron with ''Sir John Old Castell'' (as reported by Rowland White (see [[#Historical Records|Historical Records]], above). Reviewing positions by Gurr and Knutson, he offers yet another alternative, asking whether "the play performed for Carey had been lifted from their competitors' repertory" (122). Acknowledging that such "transgressions were rare," he seems more comfortable with the position that identifies the Chamberlain's play as "one of their Falstaff plays" (122). | '''Marino''' is primarily concerned with how William Jaggard [[category:William Jaggard]] came to attribute the Admiral's play, ''Sir John Oldcastle'', to Shakespeare in the so-called ''Pavier Quartos''. He discusses the moment in 1599-1600 when the Admiral's play was new and the Chamberlain's men entertained their patron with ''Sir John Old Castell'' (as reported by Rowland White (see [[#Historical Records|Historical Records]], above). Reviewing positions by Gurr and Knutson, he offers yet another alternative, asking whether "the play performed for Carey had been lifted from their competitors' repertory" (p. 122). Acknowledging that such "transgressions were rare," he seems more comfortable with the position that identifies the Chamberlain's play as "one of their Falstaff plays" (p. 122). | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''Knutson''' argues for taking Whyte's naming of the play literally (95-7). She questions whether Whyte would have known enough playhouse gossip to know also that the Falstaff character had originally been named Oldcastle. She observes further that Verreyken, as ''audiencier'' to the Austrian Archduke, might have seen in the "Oldcastle" play a reminder that his and his patron's Protestant religious positions were more in line with England than Spain. If the Chamberlain's Men did in fact acquire their own celebration of the Cobham ancestor, they had a more robust commercial and political answer to the Admiral's Men's two-part ''Oldcastle'' than killing off Falstaff in ''Henry V''. | '''Knutson''' argues for taking Whyte's naming of the play literally (pp. 95-7). She questions whether Whyte would have known enough playhouse gossip to know also that the Falstaff character had originally been named Oldcastle. She observes further that Verreyken, as ''audiencier'' to the Austrian Archduke, might have seen in the "Oldcastle" play a reminder that his and his patron's Protestant religious positions were more in line with England than Spain. If the Chamberlain's Men did in fact acquire their own celebration of the Cobham ancestor, they had a more robust commercial and political answer to the Admiral's Men's two-part ''Oldcastle'' than killing off Falstaff in ''Henry V''. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| Line 99: | Line 100: | ||

==For What It's Worth== | ==For What It's Worth== | ||

In the centrifuge that is Falstaff/Oldcastle scholarship, it is worth noting that the character called "Jockey" in ''The Famous Victories of Henry V'' (the character on whom Shakespeare supposedly based Falstaff) was called "Sir John Old-castle."<br> | In the centrifuge that is Falstaff/Oldcastle scholarship, it is worth noting that the character called "Jockey" in ''The Famous Victories of Henry V'' (the character on whom Shakespeare supposedly based Falstaff) was called "Sir John Old-castle." There is thus a non-political explanation for Shakespeare's thinking initially of his clown-figure as "Oldcastle." <br> | ||

To some degree, the association of "Oldcastle" with ''1 Henry IV'' is also an association with William Kempe, who putatively originated the character of Falstaff. But whatever play the Chamberlain's men performed on 6 March 1600, Kempe would not have been in the cast. The month before (Feb 1600) he was dancing his famous morris dance from London to Norwich. Scholars agree that he did not return to his old company but moved to Worcester's Men. In March 1602 he was "Lent ... in Redy monye ... twentyeshellinge''es'' for his necessarye vsses" by Philip Henslowe (Greg I, 163); and in August and September he was named in payments on behalf of Worcester's Men for apparel for a play unnamed (Greg I, 179-80).<br> | To some degree, the association of "Oldcastle" with ''1 Henry IV'' is also an association with William Kempe, who putatively originated the character of Falstaff. But whatever play the Chamberlain's men performed on 6 March 1600, Kempe would not have been in the cast. The month before (Feb 1600) he was dancing his famous morris dance from London to Norwich. Scholars agree that he did not return to his old company but moved to Worcester's Men. In March 1602 he was "Lent ... in Redy monye ... twentyeshellinge''es'' for his necessarye vsses" by Philip Henslowe ([[WorksCited|Greg I]], Fol. 102<sup>v</sup>, p. 163); and in August and September he was named in payments on behalf of Worcester's Men for apparel for a play unnamed ([[WorksCited|Greg I]], Fols. 115-115<sup>v</sup>, pp. 179-80).<br> | ||

There is not a guarantee that the play title, "S<sup>r</sup> Iohn Falstafe," given in the Chamber Accounts for 1612-3 refers to ''1 Henry IV''; it is as likely to refer to ''The Merry Wives of Windsor'', the title of which in quarto advertises Falstaff in advance of the merry wives ("A Most pleasaunt and excellent conceited Comedie, of Syr ''Iohn Falstaffe'', and the merrie Wiues of ''Windsor''"). Subsequent references in court documents to "Falstaff" may also be to the spin-off in which he was the star character. For court documents as late as 1620 and 1638 to make the leap from ''1 Henry IV'' to "Falstaff" to "Oldcastle" puts considerable pressure on a collective memory of the Cobhams' objections. Even if the players were the ones who drew up the schedule of plays in 1620 and 1638, they were themselves a generation away from the original offense, and it bears asking if they would keep that old wound open by substituting the Oldcastle name for Falstaff's. <br> | There is not a guarantee that the play title, "S<sup>r</sup> Iohn Falstafe," given in the Chamber Accounts for 1612-3 refers to ''1 Henry IV''; it is as likely to refer to ''The Merry Wives of Windsor'', the title of which in quarto advertises Falstaff in advance of the merry wives ("A Most pleasaunt and excellent conceited Comedie, of Syr ''Iohn Falstaffe'', and the merrie Wiues of ''Windsor''"). Subsequent references in court documents to "Falstaff" may also be to the spin-off in which he was the star character. For court documents as late as 1620 and 1638 to make the leap from ''1 Henry IV'' to "Falstaff" to "Oldcastle" puts considerable pressure on a collective memory of the Cobhams' objections. Even if the players were the ones who drew up the schedule of plays in 1620 and 1638, they were themselves a generation away from the original offense, and it bears asking if they would keep that old wound open by substituting the Oldcastle name for Falstaff's. <br> | ||

| Line 107: | Line 108: | ||

Lord Cobham might not have been among those at the post-prandial performance of “Sir John Oldcastle” at the Lord Chamblain’s London house on 6 March 1600. Perhaps the “wrencht” foot Whyte mentions (Collins, II; Letter, 25 February) was still keeping him at home. However Cobham was invested in the Verreyken visit. According to Whyte, Cobham was a candidate for appointment to commissioner for the peace treaty Verreyken was in London to facilitate (Letter, 14 February), and Cobham sent one of his coaches to Dover to transport Verreyken on the final leg of his journey to London (Letter, 16 February). In light of Cobham’s involvement in activities associated with the Verreyken mission, the choice by the Chamberlain's Men to play “Sir John Oldcastle” seems additionally diplomatic, but additionally subversive if that play was in actuality one starring Falstaff.<br> | Lord Cobham might not have been among those at the post-prandial performance of “Sir John Oldcastle” at the Lord Chamblain’s London house on 6 March 1600. Perhaps the “wrencht” foot Whyte mentions (Collins, II; Letter, 25 February) was still keeping him at home. However Cobham was invested in the Verreyken visit. According to Whyte, Cobham was a candidate for appointment to commissioner for the peace treaty Verreyken was in London to facilitate (Letter, 14 February), and Cobham sent one of his coaches to Dover to transport Verreyken on the final leg of his journey to London (Letter, 16 February). In light of Cobham’s involvement in activities associated with the Verreyken mission, the choice by the Chamberlain's Men to play “Sir John Oldcastle” seems additionally diplomatic, but additionally subversive if that play was in actuality one starring Falstaff.<br> | ||

If the Chamberlain's Men did have their own "Oldcastle" play, they doubled their participation in the "Elect Nation" brand of history play in 1600, at which time (approximately) they acquired ''Thomas Lord Cromwell'' (Q1602). | If the Chamberlain's Men did have their own "Oldcastle" play, they doubled their participation in the "Elect Nation" brand of history play in 1600, at which time (approximately) they acquired ''Thomas Lord Cromwell'' (Q1602). Recent scholarly arguments on the dates of composition and company ownership of ''Sir Thomas More'' make it a likely companion piece to the ''Cromwell'' play and thus to the Chamberlain's repertory in the early 1600s (Jowett, pp. 430-33). | ||

'''Update, 2016''': in an article in ''DSH'', Hartmut Ilsemann reports statistical testing which appears to show that linguistic features of ''Sir John Oldcastle'' are more similar to texts by Shakespeare than to texts by Munday, Wilson, or Dekker. He therefore proposes that Shakespeare wrote ''Sir John Oldcastle'' for the Chamberlain's Men, who performed it for Hunsdon; that they then, for some reason, passed it to Henslowe; and that Henslowe abandoned the Munday/Drayton/Hathwaye/Wilson play of the same title that he had paid for, instead making use of Shakespeare's. Thus, argues Ilsemann, the Chamberlain's Men's Oldcastle play was written by Shakespeare and is not in fact lost, surviving as ''Sir John Oldcastle''. | '''Update, 2016''': in an article in ''DSH'', Hartmut Ilsemann reports statistical testing which appears to show that linguistic features of ''Sir John Oldcastle'' are more similar to texts by Shakespeare than to texts by Munday, Wilson, or Dekker. He therefore proposes that Shakespeare wrote ''Sir John Oldcastle'' for the Chamberlain's Men, who performed it for Hunsdon; that they then, for some reason, passed it to Henslowe; and that Henslowe abandoned the Munday/Drayton/Hathwaye/Wilson play of the same title that he had paid for, instead making use of Shakespeare's. Thus, argues Ilsemann, the Chamberlain's Men's Oldcastle play was written by Shakespeare and is not in fact lost, surviving as ''Sir John Oldcastle''. | ||

| Line 122: | Line 123: | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — —. ''The Shakespeare Company, 1594-1642''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — —. ''The Shakespeare Company, 1594-1642''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Ilsemann, Hartmut. "The Two Oldcastles of London". ''Digital Scholarship in the Humanities'' (forthcoming: published online Sep 2016). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqw039.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Ilsemann, Hartmut. "The Two Oldcastles of London". ''Digital Scholarship in the Humanities'' (forthcoming: published online Sep 2016). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqw039.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em;">Jowett, John, ed. ''Sir Thomas More.'' The Arden Shakespeare. London: Bloomsbury, 2011.</div> | |||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Kastan, David Scott. ''Shakespeare After Theory''. New York and London: Routledge, 1999.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Kastan, David Scott. ''Shakespeare After Theory''. New York and London: Routledge, 1999.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em;">— — —. Kastan, David Scott. "Killed with Hard Opinions: Oldcastle, Falstaff, and the Reformed Text of ''1 Henry IV''in ''Textual Formations and Reformations'', eds. Laurie E. Maguire and Thomas L. Berger | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em;">— — —. Kastan, David Scott. "Killed with Hard Opinions: Oldcastle, Falstaff, and the Reformed Text of ''1 Henry IV,'' in ''Textual Formations and Reformations'', eds. Laurie E. Maguire and Thomas L. Berger (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1998), 211-27.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Knutson, Roslyn Lander. ''The Repertory of Shakespeare's Company, 1594-1613''. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Knutson, Roslyn Lander. ''The Repertory of Shakespeare's Company, 1594-1613''. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">McManaway, James G. "A New Shakespeare Document." ''Shakespeare Quarterly'', 2.2 (1951): 119-22. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2866215 JSTOR]</div style> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">McManaway, James G. "A New Shakespeare Document." ''Shakespeare Quarterly'', 2.2 (1951): 119-22. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2866215 JSTOR]</div style> | ||

| Line 130: | Line 132: | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Thomson, John A. F. "Oldcastle, John, Baron Cobham (d. 1417)." ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, May 2008. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/20674 Oxford DNB]</div style> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Thomson, John A. F. "Oldcastle, John, Baron Cobham (d. 1417)." ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, May 2008. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/20674 Oxford DNB]</div style> | ||

[[category:all]][[category:Falstaff]] [[category:Noble houses]][[category:Elect Nation plays]] [[category:Martyrs]][[category:Chamberlain's]] [[category:Globe]] [[category:Phoenix/Cockpit]][[category:Found lost plays]][[category:Shakespeare]][[category:Digital attribution methods]][[category:Medieval]][[category: duplicate plays]][[category:diplomats]][[category:Update]] | [[category:all]][[category:Falstaff]] [[category:Noble houses]][[category:Elect Nation plays]] [[category:Martyrs]][[category:Chamberlain's]] [[category:Globe]] [[category:Phoenix/Cockpit]][[category:Found lost plays]][[category:Shakespeare]][[category:Digital attribution methods]][[category:Medieval]][[category: duplicate plays]][[category:diplomats]][[category:Update]][[category:Rowland Whyte]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[[category:Roslyn L. Knutson]] | [[category:Roslyn L. Knutson]] | ||

Site created and maintained by [[Roslyn L. Knutson]], Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated 21 February 2012. | Site created and maintained by [[Roslyn L. Knutson]], Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated 21 February 2012. | ||

Latest revision as of 13:30, 25 December 2020

Historical Records

Correspondence

8 March 1599/1600: Letter from Rowland Whyte to Sir Robert Sidney

Whyte provides details of a dinner given on 6 March 1600 by the Lord Chamberlain (George Carey) during the visit by Louis Verreyken, a diplomat in the service of Archduke Albert (Collins, II. 174-6; esp. 175-6):

- "All this Weeke the Lords haue bene in London, and past away the Tyme in Feasting and Plaies; for Vereiken dined on Wednesday, with my Lord Treasurer, who made hym a Roiall Dinner; vpon Thursday my Lord Chamberlain feasted hym, and made hym very great, and a delicate Dinner, and there in the After Noone his Plaiers acted, before Vereiken, Sir John Old Castell, to his great Contentment. This Day the Lords are going to Court. My Lord Harbert wil be here vpon Wednesday, he must be the honorable Instrument of much good to your Lordship, and I find your Lordship wilbe thoroughly delt withall vpon your Return, by 600 [i.e., the Earl of Nottingham] in the Matter I soe often mentioned vnto you; if yt bring you Honor, and Contentment to all Parties, I shall thinke my self happy to haue bene the first Motioner of yt." (signed "Baynards Castell, this Saturday, 8 of March 1599")

Collins's edition, characteristically, omits some of the original letter. After "This Day the Lords are going to Court" and before "My Lord Harbert...," Whyte wrote some more sentences of news for Sidney, but nothing relevant to the performance (Brennan, Kinnamon, and Hannay, p. 439).

Government Documents

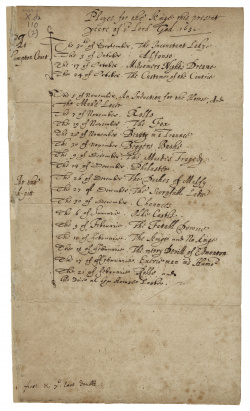

Warrant for payment from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office to Sir William Uvedale, Treasurer of the Chamber, with a list of plays performed before the King and Queen [manuscript], 1630/1 March 12:

- At the [Co]ck-pitt ... The 6 of Ianuarie ... Olde Castle.

- Folger X.d.110 (2), recto.

(CC BY-SA 4.0 licence; click image to view larger version).

Dramatic Records of Sir Henry Herbert

Henry Herbert, Court Plays acted by the King's Men, 1638-9

- At the Cocpit the 29th of may the princes berthnight ... ould Castel

Theatrical Provenance

The dinner party described by Rowland Whyte was given at Hunsdon House by George Carey, who succeeded to the title of Lord Hunsdon when his father, Henry Carey, died on 22 July 1596. He also acquired patronage of his father's company, known as the Chamberlain's Men, even though he did not himself become Lord Chamberlain until 17 March 1597 on the death of Lord Cobham. George Carey lived in Blackfriars in London, and presumably he entertained Louis Verreyken there on Thursday, 6 March. If the play performed was indeed a play about Sir John Oldcastle (and not the Falstaff character [see below]), it belonged to the repertory of the Chamberlain's Men in their first year at the Globe, 1599-1600.

Probable Genre(s)

History

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

- John Foxe describes the execution of Sir John Oldcastle in Lincoln's Inn Fields in 1419 (Actes and Monuments ... or Booke of Martyrs).

- The Oxford DNB includes the life of Oldcastle.

- In October 1599, the Admiral's Men purchased part one of a play on the life of Sir John Oldcastle from Anthony Munday, Michael Drayton, Robert Wilson, and Richard Hathway; they paid additional moneys in earnest on "the second part". In early November Munday and his collaborators were given 10s. on the performance of the play for the first time. The first part of the Admiral's play was printed in 1600, advertising itself as a first part on the title page. Sometime between 19 and 28 December, Michael Drayton was paid 80s. for the rest of the second half. The company laid out 30s. "to macke thinges" for the second part, which presumably was then staged. It is now lost.

- In August 1602 Worcester's Men paid Thomas Dekker 40s. plus another 10s. in September for "new a dicyons" to "Oldcastle" (Greg, I.179, 181). In addition the company bought apparel for the production including "a sewt for owld castell" (Greg, I.179).

- The relationship of these plays for the Admiral's Men and Worcester's Men to the play given by the Chamberlain's Men in March 1600 at the London residence of their patron is unclear, but the general biographical matter of the title character must have been shared.

References to the Play

References to a discrete play called "Oldcastle" in the repertory of the Chamberlain's Men are complicated. Historically, scholars have identified lost plays with extant ones; they have also identified lost plays with items in the Shakespeare canon. Consequently, the "Oldcastle" play discussed in Whyte's letter to Sidney has been identified with Shakespeare's 1 Henry IV on evidence that Shakespeare initially named Prince Hal's tavern companion in that play "Oldcastle" but changed the name to "Falstaff" when the Cobham family allegedly objected (Lord Cobham was Lord Chamberlain, but not also the Chamberlain's company patron, for less than a year in 1596-7). Traces of the name change are in the printed texts of 1 Henry IV (e.g., "my old lad of the castle" 1.2.41). In a Shakespeare-centric scholarly tradition, references to "Oldcastle" were interpreted as references to "Falstaff" and therefore to the extant Shakespearean first part of the Henriad. A feature of that Shakespeare-centric scholarly tradition was the belief that the Chamberlain's men would not have acquired a play on the same subject (and not have given it the same title) as a play in the repertory of another adult commercial company.

The evidence most often cited that the Falstaff-Oldcastle name switch persisted in the company's collective memory is in Amends for Ladies (Q1618) by Nathan Field, a player and dramatist who joined the King's Men c. 1615. Field appears to link Falstaff and Oldcastle in the following line: "The Play where the fat Knight, hight Old-castle/ Did tell you truly what his honour was?" (iv.3) (as quoted by Chambers, I.382).

Critical Commentary

Chambers typifies the scholars of his time by reading Rowland Whyte's naming of a play called "John Old Castell" as a reference to Shakespeare's Henry IV, part 1: "Henry IV must have been the Sir John Old Castell with which the Lord Chamberlain entertained an ambassador on 8 March 1600, since the players were his men and not the Admiral's" (1.382). Chambers also reads the 1638 performance at the Cockpit as a performance of Shakespeare's Henry IV, part 1 (i.382).

McManaway continues that opinion in an essay for Shakespeare Quarterly in which he revisits a pair of documents held by the Folger Shakespeare Library. One is a warrant authorizing the playing companies to be paid (formerly Folger MS 2068.7, now X.d.110 (1)); the other is a schedule of four performances at Hampton Court and sixteen at the Cockpit playhouse (formerly Folger MS. 2068.8, now X.d.110 (2)). The schedule lists the plays given before Charles I from 30 September 1630 through 21 February 1631. Addressing the entry on 6 January of "Olde Castle," McManaway observes that the title "is surely not" the Admiral's play written by Drayton, Munday, Wilson and Hathway (p. 121). Reciting the Whyte and Field references plus the 29 May 1638 performance as evidence of how hard it was "to efface the memory of the surname originally borne" by Shakespeare's Falstaff, he concludes that "even in Shakespeare's own company in the fourth decade after 1 and 2 Henry IV were first performed his fellows thought of the play as Oldcastle" (p. 122). JSTOR

Taylor, who is defending the restoration of the name, "Oldcastle," for Falstaff in the Oxford edition of 1 Henry IV, characterizes the references to the Oldcastle play (above) as "considerable evidence" that 1 Henry IV "was, even after 1597, sometimes privately performed with the original designation intact [of Falstaff as Oldcastle]" (p. 90). Observing that "Part 1 was sometimes referred to as 'Falstaff', ... it should not surprise us if the uncensored version were identified as 'Oldcastle'" (pp. 90-1). Documenting the alternate title of "Falstaff" for 1 Henry IV, Taylor cites three instances in court records in 1613, 1635, and c. 1619-20 (p. 90n). JSTOR

Dutton asks, "Was it Whyte or the players themselves, who kept alive the association between Oldcastle and Falstaff?" (p. 106) In answer, he explores two contexts beyond the flap about the character's name: Edmond Tilney's allowing 1 Henry IV to be licensed, even though it carried the Oldcastle name; and the possibility that, after the elder Lord Cobham died in 1597, his heir carried on the family's sense of injury (pp. 102-7).

Gurr, in The Shakespearian Playing Companies, marks Oldcastle "(lost?)" in a list of the Chamberlain's Men's plays (p. 303); in The Shakespeare Company, he appears to have changed his mind and links the Oldcastle performance at the Lord Chamberlain's house with Shakespeare's I Henry IV (pp. 170, 283).

Kastan disputes the identity of the play given at Hunsdon House as the Admiral's Sir John Oldcastle but does not consider independently the possibility that the play was the one here represented as lost. In fact, he asserts that the Chamberlain's Oldcastle was "almost certainly Shakespeare's 1 Henry IV" (p. 95). Beyond that, his argument is with Taylor's restoration of the Oldcastle name in the Oxford text of 1H4: "The restoration of 'Oldcastle' enacts a fantasy of unmediated authorship paradoxically mediated by the Oxford edition itself" (p. 102). For the lost play, perhaps the most relevant piece of Kastan's argument is his exploration of the survival of the name "Falstaff" in seventeenth-century allusions (p. 105). His crowning point is that Heminges and Condell could have restored the "Oldcastle" name under their claim to repair defective earlier quartos, but they did not (p. 106).

Marino is primarily concerned with how William Jaggard came to attribute the Admiral's play, Sir John Oldcastle, to Shakespeare in the so-called Pavier Quartos. He discusses the moment in 1599-1600 when the Admiral's play was new and the Chamberlain's men entertained their patron with Sir John Old Castell (as reported by Rowland White (see Historical Records, above). Reviewing positions by Gurr and Knutson, he offers yet another alternative, asking whether "the play performed for Carey had been lifted from their competitors' repertory" (p. 122). Acknowledging that such "transgressions were rare," he seems more comfortable with the position that identifies the Chamberlain's play as "one of their Falstaff plays" (p. 122).

Knutson argues for taking Whyte's naming of the play literally (pp. 95-7). She questions whether Whyte would have known enough playhouse gossip to know also that the Falstaff character had originally been named Oldcastle. She observes further that Verreyken, as audiencier to the Austrian Archduke, might have seen in the "Oldcastle" play a reminder that his and his patron's Protestant religious positions were more in line with England than Spain. If the Chamberlain's Men did in fact acquire their own celebration of the Cobham ancestor, they had a more robust commercial and political answer to the Admiral's Men's two-part Oldcastle than killing off Falstaff in Henry V.

For What It's Worth

In the centrifuge that is Falstaff/Oldcastle scholarship, it is worth noting that the character called "Jockey" in The Famous Victories of Henry V (the character on whom Shakespeare supposedly based Falstaff) was called "Sir John Old-castle." There is thus a non-political explanation for Shakespeare's thinking initially of his clown-figure as "Oldcastle."

To some degree, the association of "Oldcastle" with 1 Henry IV is also an association with William Kempe, who putatively originated the character of Falstaff. But whatever play the Chamberlain's men performed on 6 March 1600, Kempe would not have been in the cast. The month before (Feb 1600) he was dancing his famous morris dance from London to Norwich. Scholars agree that he did not return to his old company but moved to Worcester's Men. In March 1602 he was "Lent ... in Redy monye ... twentyeshellingees for his necessarye vsses" by Philip Henslowe (Greg I, Fol. 102v, p. 163); and in August and September he was named in payments on behalf of Worcester's Men for apparel for a play unnamed (Greg I, Fols. 115-115v, pp. 179-80).

There is not a guarantee that the play title, "Sr Iohn Falstafe," given in the Chamber Accounts for 1612-3 refers to 1 Henry IV; it is as likely to refer to The Merry Wives of Windsor, the title of which in quarto advertises Falstaff in advance of the merry wives ("A Most pleasaunt and excellent conceited Comedie, of Syr Iohn Falstaffe, and the merrie Wiues of Windsor"). Subsequent references in court documents to "Falstaff" may also be to the spin-off in which he was the star character. For court documents as late as 1620 and 1638 to make the leap from 1 Henry IV to "Falstaff" to "Oldcastle" puts considerable pressure on a collective memory of the Cobhams' objections. Even if the players were the ones who drew up the schedule of plays in 1620 and 1638, they were themselves a generation away from the original offense, and it bears asking if they would keep that old wound open by substituting the Oldcastle name for Falstaff's.

Lord Cobham might not have been among those at the post-prandial performance of “Sir John Oldcastle” at the Lord Chamblain’s London house on 6 March 1600. Perhaps the “wrencht” foot Whyte mentions (Collins, II; Letter, 25 February) was still keeping him at home. However Cobham was invested in the Verreyken visit. According to Whyte, Cobham was a candidate for appointment to commissioner for the peace treaty Verreyken was in London to facilitate (Letter, 14 February), and Cobham sent one of his coaches to Dover to transport Verreyken on the final leg of his journey to London (Letter, 16 February). In light of Cobham’s involvement in activities associated with the Verreyken mission, the choice by the Chamberlain's Men to play “Sir John Oldcastle” seems additionally diplomatic, but additionally subversive if that play was in actuality one starring Falstaff.

If the Chamberlain's Men did have their own "Oldcastle" play, they doubled their participation in the "Elect Nation" brand of history play in 1600, at which time (approximately) they acquired Thomas Lord Cromwell (Q1602). Recent scholarly arguments on the dates of composition and company ownership of Sir Thomas More make it a likely companion piece to the Cromwell play and thus to the Chamberlain's repertory in the early 1600s (Jowett, pp. 430-33).

Update, 2016: in an article in DSH, Hartmut Ilsemann reports statistical testing which appears to show that linguistic features of Sir John Oldcastle are more similar to texts by Shakespeare than to texts by Munday, Wilson, or Dekker. He therefore proposes that Shakespeare wrote Sir John Oldcastle for the Chamberlain's Men, who performed it for Hunsdon; that they then, for some reason, passed it to Henslowe; and that Henslowe abandoned the Munday/Drayton/Hathwaye/Wilson play of the same title that he had paid for, instead making use of Shakespeare's. Thus, argues Ilsemann, the Chamberlain's Men's Oldcastle play was written by Shakespeare and is not in fact lost, surviving as Sir John Oldcastle.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Roslyn L. Knutson, Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated 21 February 2012.