Isle of Dogs, The

Ben Jonson and Thomas Nashe (1597)

Historical Records

Memoranda

Bond, William Bird (Borne) with the Admiral's men in Philip Henslowe's diary

Fol. 232 (Greg, I.203)

The following entry does major work in providing a context for the lost "Isle of Dogs." It gives a date which, in conjunction with the Privy Council letters and warrants, adds to the timeline of the events. It names William Bird ("borne"), who is here contracting with Philip Henslowe to join the Admiral's men (as witnessed by Edward Alleyn and a man named Robsone). It sets the terms of the contract. And it reveals why: the restraint against playing imposed by the Privy Council "by the means of playing the Jeylle of dooges." Not every detail is equally relevant to the lost play, but the entry is repeated here in its entirety in order to document fully the one legitimate entry in the diary in terms of which the forgeries had for a time some credibility.

- Mrdom that the 10 of aguste 1597 wm borne came & ofered

- hime sealfe to come and playe wth my lord admeralles mean

- at my howsse called by the name of the Rosse setewate one the back

- after this order folowinge he hathe Receued of me iijd vpon & a

- sumsette to forfette vnto me a hundrethe marckes of lafull

- money of Ingland yf he do not performe thes thinges folowinge

- that is presentley after libertie being granted for playinge to

- come & playe wth my lordes admeralles men at my howsse

- aforesayd & not in any other howsse publicke a bowt london

- for the space of iij yeares beginynge Jmediatly after this Re

- straynt is Recaled by the lordes of the cownsell wch Restraynt

- is by the meanes of playinge the Jeylle of dooges yf he do not

- then he forfettes this asumset afore or ells not wittnes to this

- E Alleyn & Robsone

Forgeries in Philip Henslowe's diary

John Payne Collier gained access to Henslowe's manuscript (familiarly known now as Henslowe's "diary") in 1830. Edmond Malone was the first theater historian with such access, and the manuscript was returned to Dulwich College Library at Malone's death in 1812. Collier was the next scholar to have it in his hands. As the Freemans definitively argue (I.206), Collier inserted in Henslowe's manuscript three forgeries concerning "The Isle of Dogs." He first incorporated these into a narrative of 1597 in his History of English Dramatic Poetry ... and Annals of the Stage (1831), then published the forgeries themselves in his edition of the diary (1845). For further details, see Forgeries, below.

Government Documents

Remembrancia

A letter from the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of London to the Privy Council dated 28 July 1597, which calls for the suppression of playing not only in the City but also in Middlesex and Surrey, is often considered relevant to the "Isle of Dogs" affair. Omitted below is the template complaint against plays and the people who attend them; cited is the plea for playhouse closures.

- ... wee are now againe most humble & earnest sutors to yor hor: to dirrect yor lettres aswell to or selves as to the Iustices of peace of Surrey & Midlesex for the prsent staie & fynall suppressinge of the saide Stage playes, aswell at the Theatre Curten and banckside as in all other places in and abowt the Citie …. (Malone Society Collections, Vol.I, Part 1.78-79) (Chambers, 4.321)

Acts of the Privy Council

Three actions by the Privy Council have been widely perceived by scholars as relevant to the performance of "The Isle of Dogs" by Pembroke's players at the Swan in late summer, 1597. The first, dated 28 July 1597, orders the justices of Middlesex and Surrey to make certain that playhouses in their jurisdiction be "plucked down" because of the performance of lewd plays and consequent disorders. The second, dated 15 August 1597, is a letter addressed to Richard Topcliffe, a governmental inquisitor, and others (Topcliffe was "a veteran hunter of heretics and traitors, a master of the arts of torture" [Ingram, 178]). Topcliffe is instructed to learn what he can from the prisoners at hand about a play recently performed, including details of play copies and their distribution; he is further charged with a careful evaluation of papers taken from the lodgings of Thomas Nashe. The third action is the issue of warrants for the release of Gabriel Spencer, Robert Shaa (Shaw), and Ben Jonson from the Marshalsea; dated 8 October 1597 in Privy Council records, the warrants themselves are dated 3 October.

- 28 July 1597 (Dasent, 27.313-14)

... Her Majestie being informed that there are verie greate disorders committed in the common playhouses both by lewd matters that are handled on the stages and by resorte and confluence of bad people, hathe given direction that not onlie no plaies shalbe used within London or about the citty or in any publique place during this time of sommer, but that also those play houses that are erected and built only for suche purposes shalbe plucked down, namelie the Curtayne and the Theatre nere to Shorditch or any other within that county. Theis are therfore in her Majesty's name to chardge and commaund you that you take present order there be no more plaies used in any publique place within three myles of the citty until Alhalloutide next, and likewyse that you do send for the owners of the Curtayne Theatre or anie other common playhouse and injoyne them by vertue hereof forthwith to plucke downe quite the stages, gallories and roomes that are made for people to stand in, and so to deface the same as they maie not be ymploied agayne to suche use, which yf they shall not speedely perform you shall advertyse us, that order maie be taken to see the same don according to her Majesty's pleasure and commaundment. ... The like to ... the Justices of Surrey, requiring them to take the like order for the playhouses in the Banckside, in Southwarke or elswhere in the said county within iije miles of London.

- 15 August 1597 (Dasent, 27.338)

... Uppon informacion given us of a lewd plaie that was plaied in one of the plaiehowses on the Bancke Side, contanyinge very seditious and sclanderous matter, wee caused some of the players to be apprehended and comytted to pryson, whereof one of them was not only an actor but a maker of parte of the said plaie. For as moche as yt ys thought meete that the rest of the players or actors in that matter shalbe apprehended to receave soche punyshment as theire leude and mutynous behavior doth deserve, these shalbe therefore to require you to examine those of the plaiers that are comytted, whose names are knowne to you, Mr. Topelyfe, what ys become of the rest of theire fellowes that either had theire partes in the devysinge of that sedytious matter or that were actors or plaiers in the same, what copies they have given forth of the said playe and to whome, and soch other pointes as you shall thincke meete to be demaunded of them, wherein you shall require them to deale trulie as they will looke to receave anie favour. We praie you also to peruse soch papers as were fownde in Nash his lodgings, which Ferrys, a Messenger of the Chamber, shall delyver unto you, and to certyfie us th'examynacions you take. ...

- 8 October 1597 (Dasent, 28.33)

A warrant to the Keeper of the Marshalsea to release Gabriell Spencer and Robert Shaa, stage-players, out of prison, who were of lat committed to his custody. The like warrant for the releasing of Benjamin Johnson.

Correspondence of Richard Topcliffe

A letter from Richard Topcliffe to Sir Robert Cecil dated 10 August 1597 sheds light on how government officials came to be aware of "The Isle of Dogs." Topcliffe writes that the (unnamed) bearer of the letter, a man lately fallen into Cecil's disfavor, deserved better treatment, especially after his recent display of loyalty by bringing the seditious play to Topcliffe's attention:

Richard Topcliffe's 1597 letter to Robert Cecil (Cecil Papers 54/20). Reproduced courtesy of Hatfield House.

- And I have lifted vpp his hart agein wth lettinge hym knowe That her maty is so well pleassed wth hym, & yor honor also, for the prooffe He laytly mayd to mee of his loyall harte, To bee ye first man That discoverred to mee that sedyceoos play Cawlled The Ile of doggs, in his opynyon As a venemoous intent & a preparatyve to summe farrefetched myschieffe, & I cannot over often Saye was good prooffe of his Loyaltee

- (Hatfield House, Cecil Papers 54/20)

Topcliffe recommends the letter-bearer for future service ("I do not dovbt But yor honor shall finde hym Cayrefull to performe any service yow will prescrybe hym") and, in light of his dire financial straits, hopes that he might receive "summe Extraordenary favor." (As Ingram comments: "All of this may lead us to suspect that the informer's motives were less lofty than a distressed concern for the well-being of the commonwealth" [182].) While Topcliffe does not identify the letter-bearer by name, biographical clues elsewhere in the letter suggest that he may have been the informant William Udall (Teramura 47-55).

View the full letter here:

|

|

- (Cecil Papers 54/20, reproduced courtesy of Hatfield House)

Jonson, Informations to William Drummond

In conversation with William Drummond in December 1618, Jonson alluded to having suffered "close imprisonment" and being spied upon:

- In the time of his close imprisonment under Queen Elizabeth, his judges could get nothing of him to all their demands but 'ay' and 'no'. They placed two damned villains to catch advantage of him, with him, but he was advertised by his keeper. Of the spies he hath an epigram.

- (Informations, CWBJ 5.373).

It is now generally agreed that the imprisonment in question is the one for "The Isle of Dogs." The epigram Jonson refers to is apparently Epigram 59, and the spies have been tentatively identified (on the basis of Epigram 101) as two well-known former agents of Walsingham, Robert Poley and Henry Parrot (Donaldson, Life 114).

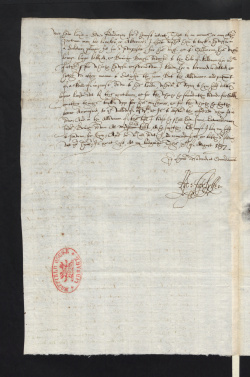

Alnwick manuscript

"A manuscript in the possession of the Duke of Northumberland at Alnwick Castle contains a number of minor works by Francis Bacon, and seems once to have been associated with Bacon himself, who served as Essex's secretary in the 1590s. A surviving outer sheet ... lists a number of writings which the manuscript once contained, and includes the entry: 'Isle of doges frmnt | by Thomas Nashe inferior plaiers'. While the 'fragment' itself has long since disappeared, the inscription appears to suggest that the piece had once been of interest to Essex and his circle" (Donaldson, Life 120; see Critical Commentary below).

|

|

| Alnwick Castle MS | Cropped image of the Alnwick Castle MS |

(Out of copyright photograph of the Alnwick Castle MS from Frank J. Burgoyne, Collotype Facsimile & Type Transcript of an Elizabethan Manuscript preserved at Alnwick Castle, Northumberland (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1904). Internet Archive.)

Theatrical Provenance

All indications are that "The Isle of Dogs" belonged to Pembroke's players at least by the summer of 1597. The company had arrived in London by February, where they leased the Swan playhouse on the Bankside. Francis Langley had had the playhouse built in the fall of 1594, and it was probably open for business by summer 1595. No documents reveal unequivocally the identity of Langley's lessees until Pembroke's players arrive in February 1597. The company's run was abbreviated in late summer.

Probable Genre(s)

Satirical comedy (Harbage)

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

None known.

References to the Play

Richard Lichfield, The Trimming of Thomas Nashe, 1597

And now you, hauing a care of your credite, scorning to lie wrapt vp in obliuion the moth of fame, haue augmented the stretcht-out line of your deedes, by that most infamous, most dunsicall and thrice opprobrious worke The Ile of Dogs: for which you are greatly in request; that, as when a stone is cast into the water, manie circles arise from it, and one succeedeth another, that if one goeth not round, the other following might be adioyned to it, and so make the full circle: so, if such infinite store of your deedes are not sufficient to purchase to you eternall shame and sorrow, there arise from you more vnder then to helpe forward: and last of all commeth this your last worke, which maketh all sure, and leaueth a signe behinde it. [marg.: Cropt ear.]. ...what all the whole yeere could not bring to passe, and all the Country long haue expected, that is, thy confusion, these dog-dayes by thine owne wordes haue effected: therfore happy hadst thou beene if thou hadst remained still in London, that thou mightest haue bin knockt on the head with many of thy fellowes these dog-daies, for nowe the further thou fleest, the further thou runst into thy calamitie: there is watch layd for you, you cannot escape; th'art in as ill a taking as the Hare, which being all the day hunted, at last concludes to dye, for (said she) whether should I flye to escape these dogs... (E4v-F1r; F3v-F4r. Lichfield offers quite a lot more in the same vein, describing Nashe's flight and anticipating his punishment).

Francis Meres, Palladis Tamia, 1598 As Actæon was worried of his owne hounds: so is Tom Nash of his Isle of Dogs. Dogges were the death of Euripedes; but bee not disconsolate, gallant young Iuuenall, Linus, the sonne of Apollo died the same death. Yet God forbid that so braue a witte should so basely perish! Thine are but paper doggies, neither is thy banishment like Ouids, eternally to conuerse with the barbarous Getæ. Therefore comfort thyselfe sweete Tom, with Cicero's glorious return to Rome, and with the counsel Æneas gives to his seabeaten soldiers. Lib. I, Æneid (Smith, II.324).

Thomas Nashe, Nashes Lenten Stuffe, 1599 In the opening section ("The Praise of the red herring"), Nashe comments explicitly on the Isle of Dogs event: "The straunge turning of the Ile of Dogs from a commedie to a tragedie two summers past, with the troublesome stir which hapned aboute it, is a general rumour laid upon me, as had well neere confounded mee ...". He speaks of the exile enforced upon him and resultant melancholy caused by "the silliest millers thombe or contemptible stickle-banck of my enemies [who are] as busie nibbling about [his] fame as if [he] were a deade man thrown amongst them to feede upon." But he promises a revenge "hot a brooding" in the form of a pamphlet that will quiet the rumors. Circling back to fallout from the play, Nashe speaks of the "unfortunate imperfect Embrion of my idle hours, the Ile of Dogs before mentioned," the conception of which was so violent that it "was no sooner borne but [he] was glad to run from it [i.e., to Yarmouth]" (McKerrow 3.153) In a marginal note, Nashe adds: "An imperfect Embrion I may well call it, for I hauing begun but the induction and first act of it, the other four acts without my consent, or the least guess of my drift or scope, by the players were supplied, which bred both their trouble and mine to" (McKerrow 3.153-4)

Thomas Dekker, Satiromastix, 1601 (S. R. 11 November 1601; Q1602) In an abrasive confrontation, Tucca, a blowhard captain, rails at Horace (Ben Jonson) that he has called Demetrius (Thomas Dekker) a "Iorneyman Poet"; Tucca then turns the insult on Horace: " but thou putst vp a Supplication to be a poore Iorneyman Player, and hadst beene still so, but that thou couldst not set a good face vpon't: thou hast forgot how thou amblest (in leather pilch) by a play-wagon, in the highway, and took'st mad Ieronimoes part, to get seruice among the Mimickes: and when the Stagerites banisht thee into the Ile of Dogs, thou turn'dst Ban-dog (villanous Guy) and euer since bitest, therefore I aske if th'ast been at Parris-garden, because thou hast such a good mouth, thou baitst well ..." (IV.i.127-35).

- In addition to the above reference to The Isle of Dogs itself and the site of the Swan ("Parris-garden"), Tucca refers to the location of the playhouse a few lines earlier: "... thou hast been at Parris garden hast not?" (4.i.122).

Anon., The returne from Pernassus (before 1603)

At the end of the satirical comedy The [second part of the] Return from Parnassus, printed in 1606 but acted in Cambridge before 1603, the satirist Ingenioso is in trouble: "To be briefe, Academico, writts are out for me, to apprehend mee for my playes, and now I am bound for the Ile of doggs"(H3r). In the following scene, he leaves London for the Isle of Dogs.

- Faith we are fully bent to be Lords of misrule in the worids wide heath : our voyage is to the ile of Dogges, there where the blattant beast doth rule and raigne Renting the credit of whom it please.

- Where serpents tongs the pen men are to write.

- Where cats do waule by day, dogges by night:

- There shall engoared venom be my inke,

- My pen a sharper quill of porcupine,

- My stayned paper, this sin loaden earth :

- There will I write in lines shall neuer die,

- Our feared Lordings crying villany. (H4r)

Ingenioso is in some respects a fictional version of Nashe, and this passage is widely taken as a reference to Nashe's play: see, for instance, Nicholl, 247.

Critical Commentary

Privy Council Orders

Wickham here stands for those theater historians who perceive the trouble at the Swan in the context of the two government missives dated 28 July 1597. He offers a timeline by which "a few days earlier" than 28 July 1597 "a play by Thomas Nashe, Ben Jonson (? and others), The Isle of Dogs, had been performed by Lord Pembroke's company at the Swan" (2:2.12). Then, the lord mayor and London aldermen, "taking advantage of the government's embarrassment, seized this chance to press their perennial claim for action against plays and players to a final conclusion by providing the Privy Council with a Memorandum" urging that playing in Middlesex, Surrey, and the City of London be suppressed (2:2.12). For its part the Privy Council, "a victim to its own action in ordering the arrest of Pembroke's men, … decided to risk meeting the City's suggestions in full by means of a public declaration of intent," i.e., by ordering that all playhouses be plucked down (2:2.12).

Ingram questions the degree of causation between the Privy Council orders to close the playhouses and the restraint issued due to concerns about the performance of "The Isle of Dogs." He points out that the lord mayor's letter is "the annual reiteration of the city's plea that plays and playhouses be suppressed" (168); he sees in it neither a significant wish by City officials "to encroach upon the jurisdictions of the Justices of Middlesex or Surrey" (170) nor any "particularly topical or immediate" offense (169). He sees the coincidence in governmental missives on 28 July as an argument against their reciprocity in that the Privy Council would not have had time to consider—much less act on—a letter written by the lord mayor that very day: "To presume that the council would respond swiftly, with a carefully worked-out order, at a time when it was otherwise occupied, to a request that it had just received, is to ask too much of the evidence" (172).

The Offense in the Play

Wickham claims that "The Isle of Dogs" criticized the government and imagines a "rowdy reception" in the playhouse that "embarrassed both the Queen and her Council" (2"2.12).

Ingram cites O. J. Campbell, who characterized the play as "explosive political satire" (176, and n.5). Arguing against scholars' and the government's position, Ingram observes that Nashe was a veteran in the business of playing and "understood the need for decorum and the limits of scurrility," as did Jonson. He takes Nashe's claim in Lenten Stuff to be "right" that the play was misunderstood (179). He also questions the motives of the informant that Topcliffe claimed to have had (179-82) and cites the players' release as evidence that "no harm seems to have been found in them" (184).

Chambers (3.455) suspects that there may have been some indiscreet reference in the play to the King of Poland, whose ambassador visited Elizabeth in July 1597.

Scoufos links the brouhaha more fully to the Cobham family through Jonson's character of Cob in Every Man In but even more extensively through Nashe's allegorical satire, Nashe's Lenten Stuff (246-62). Explicating the latter, she focuses on "the wordplay involved in cob and miller's thumb as fish," which points back to the martyred Sir John Oldcastle as well as his contemporary descendants—specifically, the young Lord Cobham (Henry Brooke), whom Nashe apparently blamed for the negative political attention paid to The Isle of Dogs.

Nicholl (like Scoufos) suggests "The Isle of Dogs" may have formed part of a group of late Elizabethan plays satirising the family of the Cobhams (see his chapter on "The Isle of Dogs," 242-56).

Donaldson (Life 118) notes that "in a letter written to Robert Cecil from another prison where he had been confined for his part in writing another play, Eastward Ho!, which had also given grave offence to those in authority, Jonson appeared to confess that The Isle of Dogs had indeed satirized the behaviour of particular individuals. ... Jonson attempts to assure Cecil that the present play is not like its predecessor:

- I protest to your honour, and call God to testimony---since my first error, which yet is punished in me more with my shame than it was with my bondage---I have so attempered my style that I have given no cause to any man of grief; and if to any ill, by touching at any general vice, it hath always been with a regard, and sparing of particular persons. I may be otherwise reported, but if all that be accused should be presently guilty, there are few men would stand in the state of innocence. (Letter 3)"

Donaldson also observes that "[n]either England's relations with Poland nor the lingering sensitivities of the Cobham family were in themselves matters of the highest political concern in England during the summer of 1597," but notes that "[o]f far greater moment were the growing danger of a new assault upon England from a revived Spanish armada, and the potential instability at home caused by the mounting rivalry between Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex, and the Cecils" (Life 118; see Alnwick manuscript above for evidence of the Essex circle's interest in this play). He points out that the play was contemporary with Essex's voyage to the Azores, and that Terceira and the Canary Islands (Latin canaria insula, isle of dogs) were both associated with dogs. He suggests the possibility of reference to that voyage: "Could Terceira have possibly been the Isle of Dogs to which Jonson's and Nashe's play referred? Did the title invoke a location in the Azores as well as in the Thames?" ("Isle of Dogs" 1.107). Like Scoufos, Donaldson queries the "series of elaborate puns on brooks and cobs" in Nashe's Lenten Stuff and Jonson's Every Man In His Humour (1598 version) as political satire of the Cobhams (Life 118).

Wright (106–13), arguing that the place name "Isle of Dogs" was used to refer to the Stepney eyots, where English warships were fitted, develops Donaldson's suggestion that the play might have "criticised national defence" during the summer of 1597 when the country was unprecedentedly vulnerable to a Spanish attack. She proposes that what John Chamberlain describes on June 11 as "a new play of humors in very great request" (McClure 1:32) refers to "The Isle of Dogs." (Most scholars assume this is a reference to Chapman's A Humorous Day's Mirth.) In a response, Hadfield and Black argue that Nashe in his other works "appears to use the name to suggest the Stepney Marshes, rather than Stepney Eyot."

Teramura observes that the informant who first reported "The Isle of Dogs" to the authorities (William Udall) had a track record of poorly substantiated accusations and a reputation for fabricating leads for his own gain (56-58). Given the dependence of the government response on the information provided by Udall, Teramura suggests that "The Isle of Dogs" may not have been as seditious as the Privy Council records imply (58-59).

Consequences for the Swan, Francis Langley, and Pembroke's Players

Wickham claims that the Swan "lost its license as a result of the performance of The Isle of Dogs in 1597: it remained closed on account of plague for several months and was never again officially allowed to function as a regular theatre" (2:1.134). He sees particular animus toward Langley: "the Privy Council regarded his offense in July of 1597 as unpardonable and had no intention of admitting him to the select band of theatre proprietors whose interests it was preparing to equate with its own. [Langley] died in 1602 and the Swan was never again regarded as a negotiable playhouse" (2:2.14). He contends that the players "left for the provinces," excepting those whom Henslowe snapped up: "within a matter of days ... he is busily engaging players and entering into bonds with them to perform at the Rose as soon as the restraint on playing is lifted" (2:2.13). Even so, Wickham says, Henslowe "set about supplementing [the residue of Pembroke's former company] with newcomers, and by the end of the year, he had met with sufficient success to send a company in Pembroke's name on an extensive provincial tour" (2:2.14).

Ingram suggests that the stoppage in performance at the Rose after 28 July may be a result of a normal slowdown in late summer or possibly "word of the inhibition" by way of players formerly with the Admiral's (Richard Jones, Thomas Downton) but currently with Pembroke's who passed on the news to their fellows (175). Ingram discusses the law suits between Langley and his "decamped" players in which both parties agreed that Langley had had players at the Swan after Bird and the others left for the Admiral's men (189-90). He concludes that Langley "continued to have players in his playhouse, despite his failure to secure a license for such activity" (196).

Forgeries

Fol. 29v (Greg, I.57) (Collier, 94)

- Lent the 14 may 1597 to Jubie vppon a notte

- from Nashe twentie shellinges more for the Jylle

- of dogges wch he is wrytinge for the company

In his edition of the diary, Collier appended a note to this entry, reinforcing his fraudulent point that Nashe was writing the play for the Admiral's men; he references the second forgery (F. 33, below), and refers the reader to a woodcut in "The Trimming of Thomas Nashe" which shows Nashe in fetters. Collier believed that Gabriel Harvey had written "The Trimming" under the pseudonym of Lichfield, but that opinion has been challenged persuasively by Griffin (48).

Fol. 33 (Greg, I.62) (Collier, 98)

- pd this 23 of aguste 1597 to harey porter

- to carye to T Nashe nowe at this tyme in the

- flete for wrytinge of the eylle of doggies ten

- shellings to be paid agen to me when he cane

- J saye ten shillings ............................. xs

In his diary edition, Collier also appended a note to this forgery, referring readers to his 1831 History of English Dramatic Poetry in which he had first announced the contents of his forged entries (he referenced his Shakespeare as well).

Fol. 33v (Greg, I.63) (Collier, 99)

- pd vnto Mr Blunsones the Mr of the Reveles

- man this 27 of aguste 1597 ten shillings for

- newes of the restraynt beinge recaled by the

- lordes of the Queenes counsel ............................. xs

Collier's note in the diary on this third forgery merely rephrases the entry.

Greg discusses the forgeries primarily in terms of the physical abuse of Henslowe's manuscript (I.xl-xli). He also observes, scornfully, that the entry concerning Blunson, the Revels man, is "the most clumsy forgery in the volume" (I.xli).

Freeman and Freeman are more candid about Collier's "fabrication-cum-forgery" (I.205). They point out that Collier tirelessly faulted Malone for omissions in his transcript, implying that it was thus easier for Collier to mix in his mischief with Malone's real and imagined omissions (I.206). They observe further than Collier's forgeries "provide the only evidence that Nashe was ever imprisoned over the affair" (I.206).

See also Wiggins, Catalogue #1081.

For What It's Worth

Touring: every scrap of documentation and commentary on "The Isle of Dogs" implies that it was newly written at the time of the brouhaha over its content in late July 1597. But if it was new then only to London audiences, the recent touring history of Pembroke's men could be relevant to venues and audiences of the play. According to the Patrons and Performances Web Site, Pembroke's men visited Bath sometime after 15 October 1596. where they performed at the Guildhall and were paid 20s. (REED PP). Since the company is known to have been at the Swan by February 1597, the travel that included Bath must have occurred between October 1596 and February 1597. At the present time, no additional stops on the way to and from Bath have been identified for the company.

S. P. Cerasano communicates via e-mail that the "Robsone" name for the man who with Alleyn witnessed Bird's bond with the Admiral's players was probably "Robinson." And, while this man cannot be identified with a certainty, Cerasano says that the person was most likely a member of the Henslowe-Alleyn circle of business friends.

Hillman draws attention to the numerous references to dogs in Nashe's Summer's Last Will and Testament (printed 1600), and to the use of the Isle of Dogs as a location in Marston, Jonson, and Chapman's Eastward Ho! (1605). He observes: "Nashe had died in 1601, but it is hard not to feel the spirit of his subversive page presiding over Eastward Ho’s re-imagined Isle of Dogs" (512).

Peachman argues that if Shakespeare's The Two Gentlemen of Verona were later in composition than is generally recognized, it might contain a series of topical references to the Isle of Dogs affair in its treatment of Crab the dog. He also draws attention to Puntarvolo's dog in Jonson's Every Man Out of His Humour as also perhaps giving clues to "The Isle of Dogs."

Curiosity: it is worth noting that there was an earlier play (also lost) about an isle of dogs, or more literally, dog-men. In the holiday season of 1576-7, Sussex's players performed a play at court on Candlemas called "The Cynocephali" (Chambers 4.93; Chambers 4.152). Feuillerat transcribes the entry in the Revels Accounts as follows: "The historye of the Cenofalles showen at Hampton Court on Candlemas day at night, enacted by the Lord Chamberleyn his men" (256). Knutson, paraphrasing Isodore of Seville, describes the Cynocephali as "creatures from India with the heads and barks of dogs" (101). Paraphrasing also Marco Polo, Knutson says that the Cynocephali, who had "faces like big mastiffs," were "a very cruel race who live on an island and devour strangers who come ashore" (101).

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Roslyn L. Knutson, Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; additions by Matthew Steggle, David McInnis and Misha Teramura. Updated 10 March 2021.