Fair Constance of Rome, Parts 1 and 2

Fair Constance, Part I

Fair Constance, Part II

Historical Records

Payments

To playwrights in Philip Henslowe's diary

Fol. 69v (Greg I.122)

Receaued of Mr Henshlowe thys 3th of June 1600 } in behalfe of the Company to An : Munday & } the rest in pte of payment for a booke Called } iijll vs the fayre Constance of Roome the some of }

lent to wm pd vnto drayton hathway Monday } hawton . . Ijs & deckers at the a poyntment of } lent mor ijs Robart shawe in full payment of a } xxxxiiijs Boocke called the fayre constance of } Rome the 14 of June 1600 some of }

l s d 12- 09- 00 Lent vnto Robart shawe the 20 of } June 1600 to lend them Hathway in } earneste of ther second pte of constance } xxs of Rome the some of . . . . . . . . . . }

Correspondence

Philip Henslowe's papers in the Dulwich College Library

Greg, Papers (MS I. 31, Article 31, pp. 55-56)

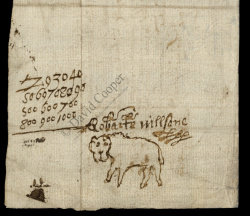

Autograph note from Robert Shaa to Henslowe, undated (Greg uses the payments above to date the letter 14 June 1600):

- J pray you mr Henshlowe deliuer vnto the bringer hereof the some of fyue & fifty shillinges to make the 3ll--fyue shillinges wch they receaued before, full six poundes in full payment of their booke Called the fayre Constance of Roome. whereof J pray you reserue for me mr willsons whole share wch is xjs. wch J to supply his neede deliuered him yesternight.

- yor lovinge ffreind Robt Shaa.

On the back is Wilson's name and a drawing of a dog:

MS I f45v (detail), ©David Cooper and reproduced with kind permission of the Governors of Dulwich College. No further reproduction permitted.

Theatrical Provenance

The Admiral's men acquired both parts of "Fair Constance of Rome" in the summer of 1600, the year the company moved from the Rose to the Fortune in autumn.

Probable Genre(s)

Classical History (?) (Harbage); Romance (Wiggins, Catalogue #1254, #1256); Secular Saint's Life? (see below)

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

Greg II (#208, #209, p. 214) proposed Chaucer's Man of Law as the clear source for these plays. Wiggins, Catalogue agrees, suggesting that the first play dramatised the material up to and including Constance's marriage to King Alla (#1254). The Riverside editors of Chaucer note that the Man of Law's Tale is in turn based on Nicholas Trivet's Anglo-Norman Chronicle and on Gower's redaction of Trivet; they compare it to the story of Patient Griselda as a type of secular saint's life (9).

Chaucer's Canterbury Tales had been published numerous times; most recently by Speght in 1598:

The Fair Constance story had also appeared independently, much earlier in the 16th century:

In Chaucer's Man of Law's Tale (citations from the Riverside edn), rich Syrian merchants plan to travel to Rome; during their stay, they learn of the existence of the Emperor’s daughter, Lady Custance [i.e. Constance], who is reportedly without peer in goodness and beauty. She is beautiful without being proud, youthful without being immature, and above all is virtuous: “To alle hire werkes vertu is hir gyde” (163). The Sultan of Syria receives the merchants upon their return, and they tell him about Lady Constance’s noble qualities; he instantly falls in love with her. His privy council advise him that the only way to attain the lady is to convert to Christianity:

- They trowe that no “Cristen prince wolde fayne

- Wedden his child under oure lawe sweete

- That us was taught by Mahoun, oure prophete.” (222-24)

The necessary arrangements are made to bring Constance to the Sultan, and she prepares herself to go, pale and unable to see any alternative. The Sultan’s mother, however, has grown concerned about her son’s imminent apostasy and what it might mean for Muslims more generally. She plans with her council to pretend to undergo baptism (“Coold water shal nat greve us but a lite!”, 352) and during the feasting that follows, have her son and his fellow Christians killed. Like Daniel in the lion’s den, Lady Constance survives the massacre by the grace of God, and she is set adrift on a rudderless ship, foundering on coast of pagan Northumberland after a lengthy period at sea.

The Constable of the nearby Northumbrian castle rescues her and, with his wife, welcomes her. The Constable’s wife, Dame Hermengild, converts to Christianity and after coming to the assistance of a blind man in Christ’s name, makes her husband believe in Christ too. Satan, however creates another challenge for Constance in the form of a local knight who, infatuated with her but unable to attain her (such is her virtue and resolve), frames her for the murder of the Constable’s wife. Whilst she and the wife lie asleep, the knight sneaks into their chamber, slits the wife’s throat, and plants the bloodied knife by Constance’s side; when the Constable returns, he assumes her guilt and reports the crime to King Alla of Northumberland. Although the knight testifies against Constance, the people cannot believe her capable of such wickedness; Alla is moved by her plight and Constance prays for a miracle to clear her of the deed. Alla calls for the knight to swear on a bible and describe the murder; he does so, and instantly meets with divine retribution:

- …on this book he swoor anoon

- She gilty was, and in the meene whiles

- An hand hym smoot upon the nekke-boon,

- That doun he fil atones as a stoon,

- And bothe his eyen broste out of his face… (667-71)

King Alla is converted to Christianity in direct response to Constance’s prayers being answered, and subsequently marries her, making her queen. Alla’s mother (Donegild), however, is insulted that her son should take a foreigner as his wife.

Alla sends Constance into the protection of a bishop and his constable whilst Alla wages war in Scotland. Constance gives birth to a boy (Mauricius), and the Constable arranges for a messenger to take a letter to Alla to relate the news. Before he leaves, the messenger tells Alla’s mother the news; she detains him for the night, encouraging him to drink heavily, then steals his letters and substitutes a counterfeit directed to the king. It advises him that Constance was delivered of “so horrible a feendly creature” (751) that she must herself be “an elf” who works “charmes” and “sorcerie” (754-55). Alla is saddened by the news but his Christian faith prompts him to reply and ask his mother to take care of Constance and the child no matter whether it is “foul or feir” (764); he prays Christ will send him a more agreeable heir in the future. The unreliable messenger is again duped into imbibing freely by Alla’s mother, who again substitutes a counterfeit letter for the genuine article; this time the letter (ostensibly from Alla) tells the Constable that Constance is to be banished from the realm and returned to sea upon the vessel that first brought her to Northumberland. The Constable reluctantly complies with the terms of the letter (he risks being hanged if he does not banish Constance), and Constance again turns to prayer and seeks protection from Christ and the Virgin Mary. When Alla returns home shortly after, he asks where his wife and son are, and the Constable shows him the falsified letter; the messenger is tortured until responsibility for the treachery can be established. Alla slays his own mother. Constance and her son survive many years at sea and are washed up on another coast near a heathen castle (904). A thief boards her ship and attempts to attack her but in the struggle falls overboard and drowns (it is understood that this is divine punishment: “Crist unwemmed [undefiled] kept Custance”, 924).

Meanwhile, Constance’s father, the Roman Emperor, has learned of the slaughter of Christians in Syria and the treachery of the Sultaness; he retaliates by attacking the Syrians, and when the offensive is completed, the Romans sail home, encountering Constance’s ship en route. A Roman Senator brings Constance home. Alla embarks on a pilgrimage to Rome to do penance; the same Senator greets him according to custom and extends him his hospitality. At a subsequent feast, Alla encounters his own son for the first time; his striking resemblance to Constance (whom Alla believes drowned at sea) forces Alla to retire early from the feast, convinced he is hallucinating. Alla later meets and recognises Constance; she faints twice, overcome with emotion at the recollection of his “unkyndenesse” (1057), but he explains to her what has happened and absolves himself of guilt. Constance is reunited with her husband, and the next day is reunited with her father, the Emperor, who has not seen her since she was sent to Syria. Constance returns to England with Alla, and when he dies a year later, she returns to Rome with their son, Maurice, who goes on to become the Christian Roman Emperor of that name (1121-23).

References to the Play

None known; information welcome.

Critical Commentary

On the basis of Henslowe's payment for part 2 just six days after paying for part 1, Wiggins, Catalogue suggests that this project appears to have been conceived from the outset as a two-part play, rather than the success of part 1 generating demand for an unplanned part 2. His assumption is "that they broke at the middle peak of Constance's fortunes, so that her marriage to King Alla provides a temporary happy ending pending the full resolution in the second part" (#1254).

For What It's Worth

Information welcome.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, 10 March 2015.

- Dulwich College

- All

- Serial/Sequel plays

- Henslowe's records

- Partial payment

- David McInnis

- Rose

- Admiral's

- Eastern

- Christianity

- Chaucer

- Exile

- Romance

- Religion

- Collaborations

- Plays

- Update

- Anthony Munday

- Michael Drayton

- Richard Hathway

- Thomas Dekker

- Robert Wilson

- Drayton, Michael

- Munday, Anthony

- Hathway, Richard

- Dekker, Thomas

- Wilson, Robert