Cloth Breeches and Velvet Hose

Historical Records

Book Trade Records

Stationers' Register

S. R. I, 3.59/161 (CLIO)

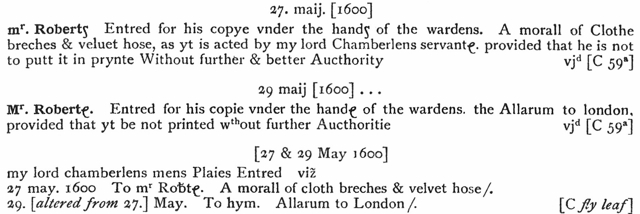

- On 27 May 1600, James Roberts paid 6d. to enter his copy of the following play into the Stationers' Register (Register C, 59a): "A morall of Clothe breches & veluet hose, As yt is Acted by my lord Chamberlens servantes." The clerk added a condition: "PROVIDED that he is not to putt it in prynte Without further and better Aucthority."

S. R. I, 3.37/fly leaf (CLIO)

- On 29 May 1600 the clerk turned to a fly leaf of Register C and began a list headed "my lord chamberlens menns plaies Entred." Following a "viz," he listed two titles: "A moral of 'clothe breches and velvet hose,'" and Allarum to London. Though he left room, no more titles were entered.

- On this authority rests the existence of the play, "Cloth Breeches and Velvet Hose," and its assignment to the repertory of the Chamberlain's men (illustrated below by Greg, BEPD 1.15).

Theatrical Provenance

"Cloth Breeches and Velvet Hose" belonged to the Chamberlain's repertory probably in 1599-1600. The fact that Roberts acquired it in May 1600 suggests that it had already been on stage, and the verb tense of the entry ("is Acted") suggests that its currency was not exhausted. The Chamberlain's men moved into the Globe playhouse in the late summer or early fall of 1599, so this play would have been among the first batch of their acquisitions for the new venue.

Probable Genre(s)

Comedy (Harbage); Estate Satire (Knutson)

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

In 1592 Robert Greene published A Quip for an Upstart Courtier, which carries the sub-title "A Quaint Dispute Between Velvet-Breeches and Cloth-Breeches." Google Books, Modern Print ed. Its title-page illustration contrasts the two estates. Quip Image

Knutson summarizes the narrative of Greene's tract as follows (61-2) (page numbers and spelling below keyed to GoogleBooks):

The entire work, Quip for an Upstart Courtier, is a series of dream visions, the last of which provides the story to go with the subtitle “A Quaint Dispute Between Velvet-Breeches and Cloth-Breeches.” In this dream, the narrator sees “an uncouth headless thing” strut arrogantly toward him from a nearby hill (9). The monstrosity—all “legs and hose”—is a pair of Velvet Breeches “whose panes, being made of the chiefest Neapolitan stuff, was drawn out with the best Spanish satin, and marvellous curiously over whipped with gold twist, interseamed with knots of pearl; the nether-stock was of the purest Granado silk” (9). The outfit is completed with rapier and “dagger gilt, point pendant” (9). Before the dreamer can react to this bizarre sight, a second monster marches soberly toward him. This figure is “a plain pair of Cloth-Breeches, without either welte or gard straight to the thigh, of white kersy, without a slop, the nether-stock of the same, sewed to above the knee, and only seamed with a little country blue” (10). It is weaponed with “a good sower bat with a pike in the end” (11). Immediately Velvet Breeches challenges Cloth Breeches for presuming to intrude, and Cloth Breeches counters that he has the prior right due to his lineage among the yeomanry. An argument ensues, in which each puts forward his claim to be the “most ancient and most worthy” (16). The dreamer, turned magistrate, impanels a jury to decide the case. He asks passersby to be jurymen, and he allows the pairs of breeches to disqualify those whose judgment they distrust. Greene used the serial presentation of potential jurors to achieve two ends: he drew distinctions between the moral postures of Cloth Breeches and Velvet Breeches; and he turned the parade of passersby into an estates satire, in which he indicted “the Disorders in all Estates and Trades” (title page).

The identification of one headless monstrosity with virtue and the other with vice is implicit in the costumes of the two, and in Greene’s text the characters repeatedly manifest their moral identities. Cloth Breeches charges Velvet Breeches with social abuses, cataloguing the sins of “vain-glory, self-love, sodomy, and strange poisonings, wherewith [he] hast infected this glorious Island” (15). Velvet Breeches brags about his favored status and thus reveals his exploitation of a corrupt socio-political system: “ I can press into the presence, when thou, poor soul, shalt, with cap and knee, beg leave of the porter to enter; and I sit and dine with the nobility, when thou art fain to wait for the reversion of the alms-basket. I am admitted boldly to tell my tale, when thou are fain to sue, by means of supplication, and that, and thou too, so little regarded, that most commonly it never comes to the prince’s hand, but dies imprisoned in some obscure pocket" (13). The jurymen, of course, find for Cloth Breeches. In rendering judgment, they affirm the virtue of Cloth Breeches, declaring him to be “a patron of the poor; a true subject; a good house-keeper, and generally as honest as he is ancient” (87). They decry the immorality of Velvet Breeches, whom they proclaim to be “begot of pride, nursed up by self-love” (87).

By choosing Greene’s narrative, the dramatist had elements of estates satire set up for him in the parade of potential jurors, who represent the shortcomings of various occupations as well as the destructive effects of the attempt to rise above one’s class. One target is the tradesman who has gotten rich because of the fashion for velvet breeches and now fancies himself a gentleman. Such is the tailor, who was once content to be “Goodman Tailor” but now styles himself “Merchant or Gentleman-Merchant-Tailor” (30). Another is the professional whose very work is corruption. Such is the broker, who is not only a loan shark but a fence, and the pairs of breeches agree that he should “be shuffled out amongst the knaves, for a discarding card” (36). There are the age-old complaints about tanners who quick-cure skins, butchers who dress old meat in fresh blood, vintners who cut good wine with sack or water, and milliners who feed an appetite for frivolous accessories. The collier shamelessly confesses his cheating, and the shoemaker takes a bit of ribbing for being in a craft where all are by nature “such good-fellows and spendthrifts” (57). The mockery of the dramatist and the stage is as familiar as the distrust of trades. Cloth Breeches chides the poet for squandering his income on food and wenches, the wanton result of which recreations is that “his plough goes and his inkhorn be clear”; but for all that, he declares the poet “no man’s foe but his own” (84). Cloth Breeches also objects to the player, whom he considers “too full of self liking and self love” (85). He is personally offended that players are too ready to bring a “plain country fellow” like himself into their plays to be laughed at “as clowns and fools” (85).

References to the Play

None known.

Critical Commentary

Knutson comments on some potentially theatrical features of Greene's source:

The text of “Cloth Breeches and Velvet Hose” may be lost, but it is easy to imagine why the Chamberlain’s men acquired it for their opening season at the Globe in 1599-1600. From the point of view of staging, the headless figures made for sensational theater. The velvet breeches and fancy hose were a nice contrast with the plain cloth breeches with blue piping. The debate between the two was enlivened by the serial appearances of tradesmen and professionals. But some measure of the dramatic appeal would have been in the dramatist’s skill in using the formulas of the dream vision, moral characterization, and estates satire from his source to convey the social, political, and economic concerns of his audience. With a successful presentation of current issues in long-familiar but still-popular literary and dramatic formulas, the Chamberlain’s men had an excellent chance of generating receipts well beyond their investment in the text and the cost of the unique costumes for the star parts. (63)

For What It's Worth

A passage in Quip apparently refers to the old ballad "Take thy old cloak about thee" in its allusion to King Stephen's frugal sartorial choices: "it was a good and a blessed time heere in Englan[d]e, when K. Stephen wore a paire of cloth breeches of a Noble a paire, and thought them passing costlye" (STC 12300, sig. C3v). In Othello, Iago sings the King Stephen stanza of the same ballad: "King Stephen was and a worthy peer, / His breeches cost him but a crown, / He held them sixpence all too dear" (Neill, ed., 2.3.81-83). Is it possible that the same stanza might have been sung when the Chamberlain's Men performed "Cloth Breeches and Velvet Hose"?

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Roslyn L. Knutson, Professor Emerita; updated 9 February 2010.