Cox of Collumpton: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

== Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues == | == Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues == | ||

Scholars have searched for town records | Scholars have searched with mixed results for town records that suggest the play material described by Forman (See [[#Cullompton or Colyton?|Cullompton or Colyton]] below). Some of the confusion is the proper name of the town in Henslowe's title. [[WorksCited|Malone]] transcribed it as "Colmiston" (p. 312). [[WorksCited|Collier]], reading Henslowe's entry as "Collinster," averred that "the true title ... was 'John Cox of Collumpton'"; he claimed that the play "related to a murder committed there" (p. 159, n.3). [[WorksCited|Greg II]] agreed with Collier about the name of the town but was “not aware of any record thereof,” although he thought the connection "very probable" ([http://www.archive.org/stream/henslowesdiary02hensuoft#page/206/mode/2up #188, p. 207]). | ||

[[WorksCited| | |||

[[category:John Payne Collier]] | [[category:John Payne Collier]] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 126: | Line 122: | ||

== References to the Play == | == References to the Play == | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

See Simon Forman's commentary on the play, above ([[#Historical Records|Historical Records]]). | See Simon Forman's commentary on the play, above ([[#Historical Records|Historical Records]]). | ||

| Line 133: | Line 128: | ||

== Critical Commentary == | == Critical Commentary == | ||

:'''Cerasano''' discusses Forman’s visit to the Rose in detail. She provides a transcription from the casebook (see above) and a context of theater history. She points out that "Cox of Collumpton" would have been “fairly new” when Forman saw it (157) and in a note to that observation she adds that, “[g]iven the time required to rehearse and mount the production, Forman might well have attended one of the earliest performances …” (157n). Cerasano describes Forman as not having “any particular critical insight” into the plays he saw, or he might “have noticed some relationship between the bear in ''Cox of Collumpton'' and that in ''The Winter’s Tale''" (which he saw in 1611) or “some similarity between Cox’s Peter, who dashes his brains out against a post, and Bajazeth in ''Tamburlaine the Great, Part I'', one of the most popular plays of the period” (158). | :'''Cerasano''' discusses Forman’s visit to the Rose in detail. She provides a transcription from the casebook (see above) and a context of theater history. She points out that "Cox of Collumpton" would have been “fairly new” when Forman saw it (p. 157) and in a note to that observation she adds that, “[g]iven the time required to rehearse and mount the production, Forman might well have attended one of the earliest performances …” (p. 157n). Cerasano describes Forman as not having “any particular critical insight” into the plays he saw, or he might “have noticed some relationship between the bear in ''Cox of Collumpton'' and that in ''The Winter’s Tale''" (which he saw in 1611) or “some similarity between Cox’s Peter, who dashes his brains out against a post, and Bajazeth in ''Tamburlaine the Great, Part I'', one of the most popular plays of the period” (p. 158). | ||

| Line 139: | Line 134: | ||

:'''Rowse''' reads the date of the performance seen by Forman as 4 March 1600 (26). | :'''Rowse''' reads the date of the performance seen by Forman as 4 March 1600 (p. 26). | ||

:'''Pitcher''' addresses the interrelationship of stage business in the playing of bears across "Cox," ''Mucedorus'' | :'''Pitcher''' addresses the interrelationship of stage business in the playing of bears across "Cox," ''Mucedorus,'' and ''The Winter’s Tale.'' He finds particularly fruitful the echo of a bear-spirit in added scenes to the 1610 quarto of ''Mucedorus'', where the clown, Mouse, claims to have just seen a bear that was really “some Diuell in a Beares Doublet” (I.ii; qtd in Pitcher, p. 50). | ||

:'''Knutson''' observes that “Forman was fascinated more by the coincidence that the murders all occurred on St. Mark’s Day than by the murders themselves” (27); she appends a note to a summary of Forman’s synopsis in which she adds two points: (1) Forman’s apparent interest in family murders, implied by his digression to the Hammon father-son murders, and (2) ''Mucedorus'', Chamberlain's Men, Q1598, as a theatrical precedent for the Admiral’s Men, should they have decided to dramatize that bear (36n). | :'''Knutson''' observes that “Forman was fascinated more by the coincidence that the murders all occurred on St. Mark’s Day than by the murders themselves” (p. 27); she appends a note to a summary of Forman’s synopsis in which she adds two points: (1) Forman’s apparent interest in family murders, implied by his digression to the Hammon father-son murders, and (2) ''Mucedorus'', Chamberlain's Men, Q1598, as a theatrical precedent for the Admiral’s Men, should they have decided to dramatize that bear (p. 36n). | ||

:'''Gurr''' connects "Cox of Collumpton" with the cluster of true-crime plays in the Admiral’s repertory for 1599, describing it as one of two “plainly journalistic accounts of sensational murders in London” although it is not apparently set in London (38). In | :'''Gurr''' connects "Cox of Collumpton" with the cluster of true-crime plays in the Admiral’s repertory for 1599, describing it as one of two “plainly journalistic accounts of sensational murders in London” although it is not apparently set in London (p. 38). In Appendix 1 (#137), Gurr repeats Henslowe’s entries, footnoting Forman’s entry using Cerasano’s date of 9 March 1600 for the show and providing a transcription of Forman’s entry (Gurr's transcription has minor typographic differences from Cerasano's). | ||

<br> <br> | <br> <br> | ||

== For What It's Worth == | == For What It's Worth == | ||

===A Collier Forgery?=== | ===A Collier Forgery?=== | ||

:'''Race''', offering a contrarian opinion, argues that the entries by Forman in his casebooks, including that for "Cox of Collumpton" are forgeries by John Payne Collier, abetted by Peter Cunningham: “My suggestion is that when Collier and Cunningham were engaged on the Shakespeare accounts they challenged one another to produce a nonsense story, and this was Collier’s effort” (14). He is particularly hard on "Cox" as a theatrical piece, asserting that “the plot is so fantastic that it is perfectly clear that the play could never have been put on the stage” (13), and that “as a narrative it reaches the depths of illiteracy” (14). <br><br> | :'''Race''', offering a contrarian opinion, argues that the entries by Forman in his casebooks, including that for "Cox of Collumpton" are forgeries by John Payne Collier, abetted by Peter Cunningham: “My suggestion is that when Collier and Cunningham were engaged on the Shakespeare accounts they challenged one another to produce a nonsense story, and this was Collier’s effort” (p. 14). He is particularly hard on "Cox" as a theatrical piece, asserting that “the plot is so fantastic that it is perfectly clear that the play could never have been put on the stage” (p. 13), and that “as a narrative it reaches the depths of illiteracy” (p. 14). <br><br> | ||

===St Mark's Day=== | ===St Mark's Day=== | ||

:St. Mark’s Day, 25 April, is an unlucky day. Fairly obviously, this is true for the Cox family, but it is also true elsewhere in early modern belief, where St. Mark’s Day functions almost as a secondary Halloween, six months apart from it in the calendar. Traditionally, St. Mark’s Eve is a night when one can see visions identifying which neighbours are to die in the next twelve months. On the day itself it was considered unlucky to work, and in particular unlucky to work the land. Early beliefs around St. Mark’s Day are conveniently collected in, for instance, Robert Chambers's [http://www.thebookofdays.com/months/april/25.htm ''Book of Days''] and William Hone's [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=gWcKAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA262 ''Every-Day Book''] (1869), 261-3. | :St. Mark’s Day, 25 April, is an unlucky day. Fairly obviously, this is true for the Cox family, but it is also true elsewhere in early modern belief, where St. Mark’s Day functions almost as a secondary Halloween, six months apart from it in the calendar. Traditionally, St. Mark’s Eve is a night when one can see visions identifying which neighbours are to die in the next twelve months. On the day itself it was considered unlucky to work, and in particular unlucky to work the land. Early beliefs around St. Mark’s Day are conveniently collected in, for instance, Robert Chambers's [http://www.thebookofdays.com/months/april/25.htm ''Book of Days''] and William Hone's [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=gWcKAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA262 ''Every-Day Book''] (1869), 261-3. | ||

| Line 180: | Line 176: | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Gurr, Andrew. ''Shakespeare’s Opposites: The Admiral’s Company 1594-1625''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. </div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Gurr, Andrew. ''Shakespeare’s Opposites: The Admiral’s Company 1594-1625''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. </div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Hone, William. ''The Every-day Book: Or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements''. [London]: [William Tegg], 1868. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=gWcKAAAAIAAJ GoogleBooks]</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Hone, William. ''The Every-day Book: Or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements''. [London]: [William Tegg], 1868. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=gWcKAAAAIAAJ GoogleBooks]</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Knutson, Roslyn L. “Toe to Toe Across Maid Lane: Repertorial Competition at the Rose and Globe, 1599-1600 | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Knutson, Roslyn L. “Toe to Toe Across Maid Lane: Repertorial Competition at the Rose and Globe, 1599-1600.” ''Acts of Criticism: Performance Matters in Shakespeare and His Contemporaries.'' Ed. June Schlueter and Paul Nelsen. Madison & Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2005. 21-37. </div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Lupić, Ivan. "Simon Forman and the Early Performances of ''Sir John Oldcastle''." ''N&Q'' 65 (2018): 98–99. DOI: [https://doi.org/10.1093/notesj/gjx206 10.1093/notesj/gjx206]</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Lupić, Ivan. "Simon Forman and the Early Performances of ''Sir John Oldcastle''." ''N&Q'' 65 (2018): 98–99. DOI: [https://doi.org/10.1093/notesj/gjx206 10.1093/notesj/gjx206]</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Pitcher, John, “‘Fronted with the Sight of a Bear’: ''Cox of Collumpton'' and ''The Winter’s Tale''.” ''Notes and Queries'', 41 (1994): 47-53. </div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Pitcher, John, “‘Fronted with the Sight of a Bear’: ''Cox of Collumpton'' and ''The Winter’s Tale''.” ''Notes and Queries'', 41 (1994): 47-53. </div> | ||

| Line 192: | Line 188: | ||

Site created and maintained by [[Roslyn L. Knutson]], Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated, 23 January 2018. Additions by Matthew Steggle. | Site created and maintained by [[Roslyn L. Knutson]], Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated, 23 January 2018. Additions by Matthew Steggle. | ||

[[category:Admiral's]] [[category:Rose]][[category:Roslyn L. Knutson]][[category:Simon Forman]][[category:Bodleian Library]] | [[category:Admiral's]] [[category:Rose]][[category:Roslyn L. Knutson]][[category:Simon Forman]][[category:Bodleian Library]] | ||

[[category:Plot | [[category:Plot details]][[category:William Haughton]][[category:John Day]][[category:Drowning]][[category:Madness]][[category:Plays]][[category:Update]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:25, 8 August 2022

William Haughton, John Day (1599)

Historical Records

Payments

To playwrights in Philip Henslowe's diary

Fol. 31 (Greg I.59)

- The 1 of novmb[er] 1599

- W. Haughton receiued of mr.

- Hunslowe in parte of payement. of the

- the tragedie of John Cox the some

- of .............................. [iij] 20s.

- Willyam Haughtonn receyued of mr Hinchloe in part

- of payment of the Tragedy of Cox of Collunpto[n]

- the som of ... 20s

- pd & quite. John Daye

Fol. 65 (Greg I.113)

Lent vnto Robart shaw the 1 of novmb[er] 1599 } to lend vnto wm harton in earneste of a } xxs Boocke called the tragedie of John cox some of ... }

F. 65v (Greg I.114)

Lent vnto wm harton & John daye at } the appoyntment of Thomas dowton in earnest } xxs pf a Boocke called the tragedie of cox of } collinster the some of ... }

the xiiijth of nouember 1599 } Receued of mr phillipp Hinchlow to pay } to William hauton & Jhon day for the } tragedy of Cox of Collomton the } iijli som of three pownd receued ... } in full }

Simon Forman's Notebooks

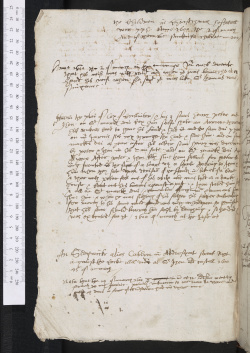

Simon Forman saw "Cox of Collumpton" at the Rose playhouse on 9 March 1600 and wrote a description of it in his casebooks (MS Ashmole 236, Fol. 77v).

(Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 236, fol77v, reproduced with permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford)

- Item in the plai of Cox of Cullinton & his 3 sonns henry peter and

- Jhon on St Markes dai Cox him selfe shote an Arrowe thorow

- his vnkells head to haue his Land & had it and the same dai 7 yers

- on Mr Jaruis shot cox throughe the hed & slue him. and on saint

- markes dai a year after his older sonn henry was drowned

- by peter & Jhon in his Xan [Christian] fate. and on St Markes dai

- A year After peter & Jhon both slue them sellues for peter be

- ing fronted wth the sight of a bear viz a sprite Apering to Jhon &

- him when they sate vpon deuision of the Landes in likenes of a bere

- & ther wth peter fell out of his wites and was lyed in a darke

- house & beat out his braines against a post & Jhon stabed him self

- & all on St Markes dai & remember how mr hammons sonn

- slue him & where he was sleying of his father his father entreating

- for mercy to his sonn could find no mercy whervpon he promised

- that his sonn should bewray him selfe by laughing & so he did &

- was executed for yt/ 1600 9 march at the Rose

- (Cerasano 157-8, with corrections from Lupić, fn5)

Theatrical Provenance

In 1599, when paying Haughton and Day for a "Cox" play ("of collinster," "of Collomton"), the Admiral’s Men were anticipating the move to their soon-to-be-built playhouse, the Fortune, in Middlesex; they were also looking across Maid Lane at their competition in the form of the Chamberlain’s en, newly moved from Shoreditch to the Globe.

The play was still in production on 9 March 1600 (a Sunday), when Simon Forman saw it at the Rose and recorded a reaction to it in one of his casebooks (see below).

Probable Genre(s)

Tragedy (Harbage; also Wiggins, Catalogue #1215)

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

Scholars have searched with mixed results for town records that suggest the play material described by Forman (See Cullompton or Colyton below). Some of the confusion is the proper name of the town in Henslowe's title. Malone transcribed it as "Colmiston" (p. 312). Collier, reading Henslowe's entry as "Collinster," averred that "the true title ... was 'John Cox of Collumpton'"; he claimed that the play "related to a murder committed there" (p. 159, n.3). Greg II agreed with Collier about the name of the town but was “not aware of any record thereof,” although he thought the connection "very probable" (#188, p. 207).

References to the Play

See Simon Forman's commentary on the play, above (Historical Records).

Critical Commentary

- Cerasano discusses Forman’s visit to the Rose in detail. She provides a transcription from the casebook (see above) and a context of theater history. She points out that "Cox of Collumpton" would have been “fairly new” when Forman saw it (p. 157) and in a note to that observation she adds that, “[g]iven the time required to rehearse and mount the production, Forman might well have attended one of the earliest performances …” (p. 157n). Cerasano describes Forman as not having “any particular critical insight” into the plays he saw, or he might “have noticed some relationship between the bear in Cox of Collumpton and that in The Winter’s Tale" (which he saw in 1611) or “some similarity between Cox’s Peter, who dashes his brains out against a post, and Bajazeth in Tamburlaine the Great, Part I, one of the most popular plays of the period” (p. 158).

- Traister comments on Forman’s visit to the Rose, calling the play Cox of Cullinton, a.k.a., Cox of Collumpton, but provides no further information or transcription beyond the citation of MS Ashmole 236, fol. 77v.

- Rowse reads the date of the performance seen by Forman as 4 March 1600 (p. 26).

- Pitcher addresses the interrelationship of stage business in the playing of bears across "Cox," Mucedorus, and The Winter’s Tale. He finds particularly fruitful the echo of a bear-spirit in added scenes to the 1610 quarto of Mucedorus, where the clown, Mouse, claims to have just seen a bear that was really “some Diuell in a Beares Doublet” (I.ii; qtd in Pitcher, p. 50).

- Knutson observes that “Forman was fascinated more by the coincidence that the murders all occurred on St. Mark’s Day than by the murders themselves” (p. 27); she appends a note to a summary of Forman’s synopsis in which she adds two points: (1) Forman’s apparent interest in family murders, implied by his digression to the Hammon father-son murders, and (2) Mucedorus, Chamberlain's Men, Q1598, as a theatrical precedent for the Admiral’s Men, should they have decided to dramatize that bear (p. 36n).

- Gurr connects "Cox of Collumpton" with the cluster of true-crime plays in the Admiral’s repertory for 1599, describing it as one of two “plainly journalistic accounts of sensational murders in London” although it is not apparently set in London (p. 38). In Appendix 1 (#137), Gurr repeats Henslowe’s entries, footnoting Forman’s entry using Cerasano’s date of 9 March 1600 for the show and providing a transcription of Forman’s entry (Gurr's transcription has minor typographic differences from Cerasano's).

For What It's Worth

A Collier Forgery?

- Race, offering a contrarian opinion, argues that the entries by Forman in his casebooks, including that for "Cox of Collumpton" are forgeries by John Payne Collier, abetted by Peter Cunningham: “My suggestion is that when Collier and Cunningham were engaged on the Shakespeare accounts they challenged one another to produce a nonsense story, and this was Collier’s effort” (p. 14). He is particularly hard on "Cox" as a theatrical piece, asserting that “the plot is so fantastic that it is perfectly clear that the play could never have been put on the stage” (p. 13), and that “as a narrative it reaches the depths of illiteracy” (p. 14).

St Mark's Day

- St. Mark’s Day, 25 April, is an unlucky day. Fairly obviously, this is true for the Cox family, but it is also true elsewhere in early modern belief, where St. Mark’s Day functions almost as a secondary Halloween, six months apart from it in the calendar. Traditionally, St. Mark’s Eve is a night when one can see visions identifying which neighbours are to die in the next twelve months. On the day itself it was considered unlucky to work, and in particular unlucky to work the land. Early beliefs around St. Mark’s Day are conveniently collected in, for instance, Robert Chambers's Book of Days and William Hone's Every-Day Book (1869), 261-3.

- Hone's account includes the following description:

- This was a great fast-day in England during the rule of the Romish church. An old writer says, that in 1589, "I being as then but a boy, do remember that an ale wife, making no exception of dayes, would needs brue upon Saint Marke's days; but loe, the marvailous worke of God! whiles she was thus laboring, the top of the chimney tooke fire; and, before it could bee quenched, her house was quite burnt. Surely," says this observer of sainted seasons, "a gentle warning to them that violate and profane forbidden daies"… On St Mark's day blessings on the corn were implored. According to a manuscript of Mr. Pennant's, no farmer in North Wales dare hold his team on this day, because they there believe one man's team that worked upon it was marked with the loss of an ox. A Yorkshire clergyman informed Mr. Brand, that it was customary in that county for the common people to sit and watch in the church porch on St. Mark's Eve, from eleven o'clock at night till one in the morning. The third year (for this must be done thrice,) they are supposed to see the ghosts of all those who are to die the next year, pass by into the church. When any one sickens that is thought to have been seen in this manner, it is presently whispered about that he will not recover, for that such, or such an one, who has watched St. Mark's Eve, says so. This superstition is in such force, that, if the patients themselves hear of it, they almost despair of recovery. Many are said to have actually died by their imaginary fears on the occasion. (Hone, 261-2)

- This complex of ideas is clearly relevant to our play. As is implicit in Hone's account, too, St. Mark’s Day lay also on one of the fault lines of the Reformation. Henry VIII abrogated the observance of St. Mark’s Day, and there were at least two separate provincial disputes in the 1530s arising from controversy over whether or not to obey Henry’s instructions in this respect (Shagan, Popular Politics, 57-9). This might remind one of other domestic tragedies such as Arden of Faversham, where Arden's status as an indirect beneficiary of the Reformation seems to be in some way linked to his horrible (and supernaturally flavoured) fate.

Cullompton or Colyton?

- Since this is thought to be a true-crime play dramatizing recent events, it would be desirable to nail down its historical basis. No such historical basis is known, apart from the vague claim by Collier that there was such a murder. But if this is indeed a true-crime play, is it possible to make any progress towards identifying its point of origin?

- First of all, as the entry above shows, the place-name is spelt differently across the early records, so much so that Wiggins, Catalogue (#1215) even wonders if the different spellings demonstrate uncertainty about whether or not to use a real place-name. Most critical discussions of the play standardize on "Cullompton" as the spelling, and see it as referring to the small town of that name in mid-Devon, twelve miles north of Exeter. The problem is that that place has no known link to any family called Cox. For instance, the FamilySearch website, www.familysearch.org, seems not to have any records of Coxes living in Cullompton before the date of the play.

- However, the process of following up this lead reveals a different possibility, in the shape of another small town, also in Devon, with a similar name. This is the town whose name is now generally standardized as Colyton, about twenty miles east of Exeter, near the coast and not far from Axminster. There are plentiful traces here, from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, of a numerous and well-established yeoman family by the name of Cox. The parish register records sixteenth-century Colyton Coxes bearing first names including Peter (1557), Harry (1575), and John (1577, 1599). It also shows the relatively uncommon first name "Jarvis" cropping up in baptisms of 1579, 1607, and 1635, suggesting that this too might be a Colyton name. And there is even a numerous local family called Hayman. Clearly, given the freedom with which early true-crime drama treats factual details such as names; and given the fact that our knowledge of the play's names themselves is almost all through Forman, whose accounts where they can be checked are often inaccurate; it would be a brave scholar who put too much weight on this connection as it stands. Nor does it (yet) lead to any more specific records of events that might underlie this play. Nonetheless, if one were setting out to search hard for information about the historical originals of these fictional characters, the Coxes of Colyton might be a family to consider.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Roslyn L. Knutson, Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated, 23 January 2018. Additions by Matthew Steggle.