Vestal, The

Henry Glapthorne (c.1633-1642)

Historical Records

Stationers' Register

On 29 June 1660, the printer Humphrey Moseley entered on the Stationers' Register a list of twenty-six plays, including:

- The Vestall. a Tragedy. }

- The noble Triall. a Tragicomedy } by Hen: Glapthorne.

- The Dutchesse of Fernandina. a Tragedy }

- (SR2, 2.271, CLIO)

Warburton's List

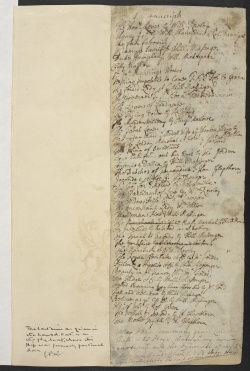

"The Vestall A Tragedy by H. Glapthorn" is listed among the manuscript plays which Warburton claimed had been destroyed by his cook:

- (British Library, Lansdowne MS 807, fo.1r. Reproduced by permission of the British Library. Click image to view full page; click here for more information on Warburton's list)

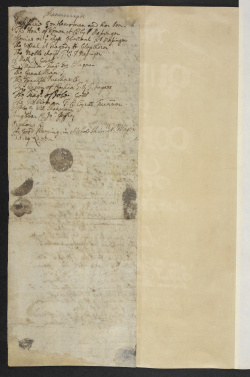

Warburton includes the play again further down the list as "The vestal a Tragedy H. Glapthorn":

- (British Library, Lansdowne MS 807, fo.1v. Reproduced by permission of the British Library. Click image to view full page; click here for more information on Warburton's list)

Theatrical provenance

Unknown. Glapthorne is known to have been active throughout the 1630s, for a range of different dramatic companies (see below). The date range given above is from Harbage.

Probable genres

Tragedy (per Stationers' Register entry); presumably, Roman tragedy.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

The Vestal Virgins, priestesses of the hearth-goddess Vesta in Ancient Rome, were well known in the English Renaissance through dozens of classical references to them. In particular, they were proverbially famous for their vows of virginity. If they infringed these vows, they were ritually entombed alive.

As a sample of such classical references, this is Pliny's account of Cornelia, a Vestal Virgin sentenced to death - perhaps unjustly - by the Emperor Domitian in 83 AD:

- Domitian generally raged most furiously where his evidence failed him most hopelessly. That emperor had determined that Cornelia, chief of the Vestal Virgins, should be buried alive, from an extravagant notion that exemplary severities of this kind conferred lustre upon his reign.

- Accordingly, by virtue of his office as supreme pontiff, or, rather, in the exercise of a tyrant’s cruelty, a despot’s lawlessness, he convened the sacred college, not in the pontifical court where they usually assemble, but at his villa near Alba; and there, with a guilt no less heinous than that which he professed to be punishing, he condemned her, when she was not present to defend herself, on the charge of incest, while he himself had been guilty, not only of debauching his own brother’s daughter, but was also accessory to her death: for that lady, being a widow, in order to conceal her shame, endeavoured to procure an abortion, and by that means lost her life. However, the priests were directed to see the sentence immediately executed upon Cornelia. As they were leading her to the place of execution, she called upon Vesta, and the rest of the gods, to attest her innocence; and, amongst other exclamations, frequently cried out, “Is it possible that Cæsar can think me polluted, under the influence of whose sacred functions he has conquered and triumphed?” Whether she said this in flattery or derision; whether it proceeded from a consciousness of her innocence, or contempt of the emperor, is uncertain; but she continued exclaiming in this manner, til she came to the place of execution, to which she was led, whether innocent or guilty I cannot say, at all events with every appearance and demonstration of innocence. As she was being lowered down into the subterranean vault, her robe happening to catch upon something in the descent, she turned round and disengaged it, when, the executioner offering his assistance, she drew herself back with horror, refusing to be so much as touched by him, as though it were a defilement to her pure and unspotted chastity: still preserving the appearance of sanctity up to the last moment; and, among all the other instances of her modesty, “She took great care to fall with decency.”

- (Pliny the Younger, Letter 43, tr. William Melmoth, cited from the online edition at Project Bartleby, http://www.bartleby.com/9/4/1043.html).

References to the Play

None known (but see "Critical Commentary").

Critical Commentary

"Moseley's entire list of 29 June 1660 is a curious one", comments Bentley (4.493-4), observing that most of the plays on it have disappeared.

W. W. Greg argued that Warburton may not have possessed the manuscripts that he claims to have lost. His list, argues Greg, derived from Stationers' Register records, including Moseley's list, and cannot be regarded as possessing an independent authority. John Freehafer, however, has made a strong argument to the contrary (Greg, "Bakings of Betsy"; Freehafer; see also Warburton's List).

Henry Glapthorne is one of the unsung journeymen of Caroline drama. His six surviving plays include comedy, tragicomedy, and the tragedy Revenge for Honour/The Parricide; his playwriting career seems to have extended from around 1630 to around 1640, and to have involved a range of companies including the King's Men, Queen Henrietta's Men, and Beeston's Boys. His surviving work tends towards the derivative and repetitive, but that does not make it uninteresting: indeed, Julie Sanders comments that "Glapthorne's plays have slipped from notice but they remain strong examples of Caroline drama and of the age's sensibility and taste."

F. G. Fleay (BCED, 1.246) guesses that The Vestal is simply an alternative title for Glapthorne's Argalus and Parthenia. This guess is generally regarded as baseless (e.g. Bentley, 4.493-4). Fleay (2.340) also argues that a reference in The London Chanticleers to "chaste Vestals" is specifically an allusion to this lost play: an idea which, again, Bentley writes off as without merit.

It has also been suggested that The Vestal might survive as a palimpsest, in the form of Sir Robert Howard's The Vestal Virgin, or the Roman Ladies, a tragedy performed in 1663. However, John Harrington Smith refutes this suggestion, observing that Howard's play is actually based heavily on the French heroic romance Artamène, which would have been unavailable to Glapthorne. Smith also offers a plot summary of Howard's play, and useful further discussion of it.

For what it's worth

Vestal virgins are famed, above all, for their vows of chastity, and for being buried alive when those vows are - or are suspected to be - broken. Roman history offers various possible source stories about members of the order who underwent entombment, whether justly or unjustly accused, of which the story of Cornelia (given above) is an illustrative example. For Glapthorne, stories of Vestal virgins would offer particularly direct access to his culture's fascination with the interrelationships of female chastity, female desire, and death.

There are two other plays in the database Literature Online, both also tragedies, which use the word "vestal" in their titles. One is Robert Howard's Roman play The Vestal Virgin, discussed briefly above, which features - actually as a relatively minor character - a young woman who has been brought up by the Vestal Virgins. In the play, though, almost no stress is put on her Vestal connections, the fact being hardly mentioned after her first appearance, and she eventually stabs herself to be with her lover who has been killed in the course of the play's intrigues. The other play is Henry Brooke's The Vestal Virgin (1789), in which the eponymous Vestal Virgin, Lavinia, is forced to choose between succumbing to the sexual advances of the wicked Great Pontiff Valerius, and being falsely accused by him and buried alive. She chooses the latter course, being entombed alive onstage at the end of Act Four, with great ceremony. She is rescued by her proper lover in Act Five, only to die in his arms immediately thereafter.

If one were looking to forecast the likely content of Glapthorne's tragedy about a Vestal Virgin, one would predict an episode in which she is entombed alive onstage, on the pattern of Brooke's play and of most of the classical stories about Vestal Virgins.

Works Cited

Brooke, Henry. The Vestal Virgin in Poems And Plays, By Henry Brooke, 2nd edition (London: John Sewell,1789), cited from Literature Online.

Fleay, F. G. A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama, 1559-1642. London: Reeves and Turner, 1891. Print. Internet Archive

Freehafer, John. "John Warburton's Lost Plays", Studies in Bibliography (1970) 154-164.

Greg, W. W. “The Bakings of Betsy.” The Library, 3rd series. 7.11 (1911): 225-259. Print.

Sanders, Julie. ‘Glapthorne, Henry (bap. 1610)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [1].

Smith, John Harrington. "The Dryden-Howard Collaboration", Studies in Philology 51 (1954): 54-74.

Page created and maintained by Matthew Steggle, Sheffield Hallam University. Revised 11 May 2015.