Play about the Duke of Florence (BL Add MS 88878)

Anon. (Shirley? Webster?) (1630s)

Historical Records

BL Add MS 88878 (images)

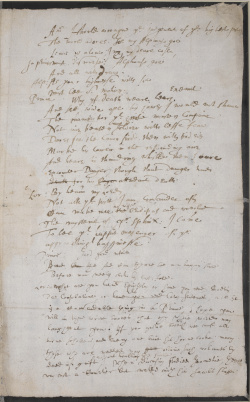

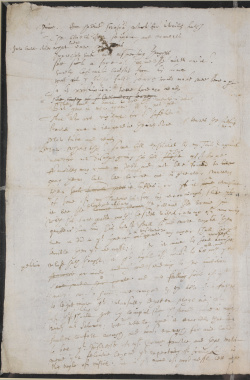

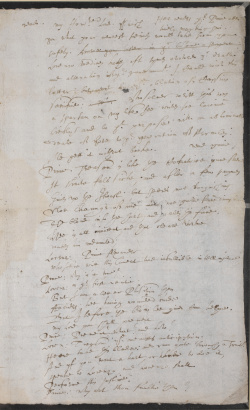

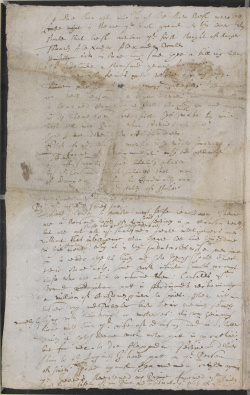

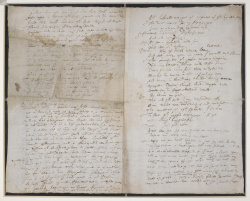

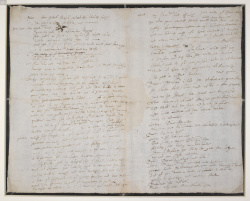

This manuscript play fragment exists only as a single sheet of paper (2 folios / 4 pages) in length. The first page features a number at the top (2) and begins part-way through a scene, preserving 144 lines in total of an early Stuart play-scene in draft form. (BL Add MS 88878):

|

|

| BL Add MS 88878, fol.1r. | BL Add MS 88878, fol.1v. |

|

|

| BL Add MS 88878, fol.2r. | BL Add MS 88878, fol.2v. |

All images (c) British Library. Reproduced by permission.

NB. The above images have been cropped into pages to display the text in order. The following openings illustrate the sheet of paper itself:

|

|

| BL Add MS 88878, fol.2v-1r. | BL Add MS 88878, fol.1v-2r. |

BL Add MS 88878 (transcription)

[Fol. 1r]

2.

And I should wrongue ye. iudgement of ye. highest policy

The world adores. Goe my Alphonso goe

Leaue vs alone; I & my deare cosen,

In priuat must discourse: Alphonso goe

And all withdraw.

Alp: As your highnesse wills soe

Must bee or. motion: Exeunt.

Prince. Why yf death weare heare

And sett wide ope his iawes I would not shune

The chamber for ye. grizlie monsters Companie.

Not anie beaten soldier with lesse feare

Dares see the Canon firde. then with fixd eies

Marke his Carreir in the resounding aire

And heare his thundring whistle then I dare

Encounter Danger, though that daunger had

death for his Page attendant death.

Lor: By heau’n my Lord

Not alle ye. witt I am Commander of

Can make mee the \a wise/ OEdipus and vnvolue

The mysterie of yr. Sphinx: I Came

To bee ye. happie messenger of yr.

approachinge happinesse.

Prince: Good good infaith

And Can the And Can theare bee an happy state

Before man meetes with his last. fate.

Lor: What are you lucid Epictetus; or haue you read Boetius

de Consolatione or haue you read \els/ Catos sentences; well: it

is a Commendable thing in a Prince, I hope you

will in tyme write bookes, that the whole world may

laugh at you. Yf you growe bookish wee must all

turne schollers, and euery one buie his horne book; marry

those who are wedded, may gett obtaine such volumes by

deed of guift; \without troubling the stationer/ When Dionisius studied

Geometrie, theare

was not a Courtier but walkd with his Iacobs staffe.

[Fol. 1v]

Prince. Can horrid Treason, which for intrailes hath

The bowels of a serpent, and Conuerts

Into burnt choler what \soere/ eare hee <ea>tes

Oppressed Euer with suspecting thoughts,

sett such a face of harmelesse mirth on it?

Surely Castruchio banisht from his home

will not by these false feares would make mee leaue apart

In his proscription: heere Lorenzo read

The Causes of Alexanders feares

\Then haue a hart to doe the mention deed/

But giue it mee againe; it is not fitt

That who are vigilant for or. safetie

should putt in ieopardie theire owne teares the subscrip

Now take and read; tion

Lorenz. Whats this? some bill exhibited by my Tailor. against

mee for not discharging his bill; slight \why/ yf I hope

ffauorites may runne in debt, and not bee forced to bee

pay them, but bee borne out in greater matters

then such small pettie trifles: or ys it some \a/ Complaint

of some of my Tauerners for his recconings, slide yf

it bee Ile Coniure his Coat \clapperclaw/ the villaine, Ile braine him

with his owne potle pots; besides withdrawing of my roaring

quaffers from him, his howse shall stand more emptie then

euer it did in ye. tyme of plague \a visitation/ : my anger shall bee more

terrible than ye. red crosse!: Or it maie tis some \opprest/ damosell

petition, whose hath thought it ye. hight of honor. to bee \all. one/ with your

ffauorite priuado, and I condescending to her ambition

haue made her greate and now fealing sicke of yt

mother, wo<uld> haue mee compeld by the title of a father

to legitimate ye. vnlawfully begotten progenie; why

yf thi\e/se \things/ should goe by compulsion I should haue as

many wiues as Salomon: noe \noe/ weele haue it enacted that it

shalbee comfort enough, and honor. enough for anie ladie

to bee ye. Mistresse of ye. Princes fauorite, and that Matri-

monie is a felicitie beyond ye. expecting of fraile Ladies in

this vayle of miserie: but in ye. name of goodnesse lett mee

[Fol. 2r]

read. my Honored. Lord. I wish Hee reades ye. Prince atten-

tiuely marking him.

you, what your nearest freinds would take from you

safety. Knowe you foster in yr. bosome a serpent:

Lorenzo Medices hath oft tymes avowed yr. death

and alteration of ye. gouernmt. I Could wish this

latter; but not by ye. oblation of Cassius

sacrifice: w whosoeuer writt this was

a spartan on my life, hee writes soe laconicê

breifly and to ye. purpose; with an abhominable

deale of love to ye. generation of Hercules:

Ile gett it without booke. read againe

Prince. Treason is like the Cockatrice once seene

It straite fals sicke, and after a few pangues

Giues vp the Ghoast. but heeres noe languishing

Noe chaunge of hue, bu<t> noe guiltie feare driues back

The bloud in to the hart, and pales the face.

Hee is all innocent, and that cleare virtue

makes him vndaunted;

Lorenz: Prince Alexander

who soe’re writt this caueat had infallible intelligence;

Prince: why is it true?

Lorenz: as ye. first veritie

But I am a better Phisitian then

Æacides; hee hauing wounded curde

But I before the blow bee giuen Can helpe.

My Lord, you shall preuent

Prince: Preuent? what? and how?

Loren: Treason: ye. meanses anticipation.

Heere take this blade: and run quite through a Traitor

And yf you want a hart, or hande to doe it,

speake to Lorenzo, and Lorenzo shall

Performe this Iustice:

Prince: why art thou faultie then?

[Fol. 2v]

I knowe thou art not by ye. love thow owest mee tell

Lor.mee what is theare ye. least ground of this letter? why

should that brest harbour ye. first thought of danger

Towards Alexander, Alexander would

Himselfe with his owne hands saue thee a killing labor

I had I h hade liude a thousand yeares too longue

< > nearest freinds growe wearie of my being.

<Taken> <>eep> < >er doubtefull: I aduise thee

Lor: well treason <is> a < >gian devill an<d> y<our> <Hono>r

a learned Co< >r. it shall Comme vp, and appear

in its likenesse but first hee \must/ make his waie.

first tell mee Prince what services of state

haue I not done; how oft discouered

Plots of ye. ban<isht> partie, who would innovate

The forme of g<o>uernment; who did preuent

<The> last surpri<se> soe likely probable

by ye. conspiracie of saluiatto that man

of daunger < >d for his Cardinalls cap.

< > ye. states of Italie;

< >ie state.

Pr: ye. world saies soe:

Lor: Now I Come to proue my selfe treache< >us; Theare

are a thousand waies of doing \good/ services in a Common wealth,

but are not all \those who doe these services/ yr. statesmen greate

intelligencers and

without this intelligence Can theare bee anie thing done

in this \Common/ wealth:\er < >/ why it is the spectacles wise men putt

on to reade others liues, and how they should direct

their owne acts. some with infinite summes corrupt

those who are able to informe them; Consales ye.

Graund Capitan, putt in fferdinands reckoning

a million of Crownes giuen to spies. Others with an

easier way, and sweeter know their enemies secrets

namely by lying with their wiues or mistresses; this was seianus

tricke with Liuia ye. wife of Drusus; and in or. latter

daies it hath beene much more putt in practice:

but for mee to doe Alexander service to deliuer

Ilium to ye. Argiues I haue put on ye. Person

of sinon; spoke against Agammemnon, rayld against

ye. Greekes, thereatened my Prince fauored ye. Exiles

<&> all for ye. safety of my Prince, and to discouer ye. plots of ye. Exiles

Theatrical Provenance

There is no recorded evidence of a performance of a play corresponding to this fragment of text. Nevertheless, it bears similarities to Act 2, Scene 1 of James Shirley’s play The Traitor, which was written in 1630, licensed for performance on May 4, 1631, and probably first performed by Queen Henrietta Maria’s company before being taken over by Beeston’s Boys (Bentley 1941). Since the language of the manuscript ties it quite definitively to 1630–35, the precise period when The Traitor was written, performed, and published (Smith 2017), we must assume that the texts were at least contemporary with one another if not more closely connected. It is possible, but by no means definite, that the Melbourne Manuscript is a foul-paper (draft) version of The Traitor 2.1.

Probable Genre(s)

Tragedy, though the dramatic writing is interspersed with humour and bawdy jokes.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

The scene recorded in the manuscript presents the historical Duke of Florence, Alessandro de’ Medici (1510–1537), here called Prince Alexander, and his cousin Lorenzino de’ Medici (1514–1548), here Lorenzo. The manuscript depicts a scene in which Alexander, having received a letter from a political exile, Castruccio, accusing Lorenzo of treason, dismisses his courtiers before confronting Lorenzo himself. Alexander makes Lorenzo read the letter to find out whether there is any foundation for this severe allegation. Lorenzo jokes about the letter’s style but admits the allegations are true. He then reminds Alexander of his previous loyalty and claims he was acting as a double agent in order to infiltrate enemy circles. The real-life Alessandro de’ Medici was in fact murdered by Lorenzino, who subsequently claimed he had acted in the civic interest by assassinating a tyrant, so we can might assume that Prince Alexander was eventually to be assassinated.

The most credible likely inspiration for Melbourne’s author is Paolo Giovio’s History of His Own Times (Latin edition 1550–52): a chronicle of the Italian Wars of 1494 to 1559. Although Carter points to Marguerite of Navarre’s Heptameron as a more likely source for Shirley’s equivalent play, Bawcutt discovered in the plots of both texts many more detailed similarities with Giovio’s History; specifically, the historical moment they dramatize is absent from Navarre’s version of the story, but present in Giovio’s. Smith (2017) accepted Bawcutt’s narrative as most persuasive in his 2017 edition of the Melbourne MS.

References to the Play

Aside from the thematic similarities tying Melbourne to Shirley’s Traitor, there do not seem to be any contemporary references to this play. Where Webster’s authorship has been considered, his dedicatory epistle in The Devil’s Law Case, addressed to Sir Thomas Finch, has been cited:

“Some of my other Works, as The white Deuill, The Dutchesse of Malfi, Guise, and others, you haue formerly seene” (Berger and Massai 1; Greg 388)

“Guise”, now lost, was probably written c.1615. Although references to Guise imply it is a tragedy, no evidence supports any link to the Melbourne MS.

Critical Commentary

The text in the manuscript has received literary critical attention from Pryor, Hammond and Del Vecchio, and Smith (2017). Each comments on the richness of the drama, the comedy, characterisation, and the use of language, with Pryor describing the manuscript as “a richly worked, subtly ironic, dense piece of literary composition” (Smith, 2017) and Smith asserting that “[t]he play, had it ever been completed, would have stood comparison with any of the great Jacobean or Caroline tragedies” (612).

Academic discussion of this manuscript has been dominated by the question of authorship. The manuscript may have been composed by an otherwise unknown amateur author, albeit one of considerable skill, or one of the professional playwrights whose entire corpus is now lost. Modern academic discussions have pointed to only two serious contenders, John Webster and James Shirley.

Shapiro claimed the author must have been Shirley on the basis of disputed palaeographical evidence. When Hammond and Del Vecchio examined the document in 1988, they concluded that Webster was the more likely candidate based on stylistic interpretations. Jackson significantly updated scholarship on the authorship question in 2006, producing stylometric conclusions that pointed to Shirley not just over Webster but over all other known contemporary dramatists. Although Webster is now out of favour and Shirley is currently considered the most likely candidate, the fragment’s authorship remains unknown; Beal’s CELM lists the manuscript among Shirley’s works, but with the caveat that “the matter remains unresolved”. Smith (2017) while acknowledging the stronger claims for Shirley, ultimately averred. Based on his reading of the palaeographical evidence, he suggested that Melbourne might have been “written by two hands”, and could thus constitute evidence of literary collaboration – necessarily muddying attempts to assign authorship through stylometrics.

A further critical discussion prompted by the manuscript’s discovery considers its bibliographical status: the Melbourne Manuscript preserves ambiguous but illuminating evidence about a rarely witnessed stage in the production of early modern dramatic texts, the draft. Displaying evidence of deletions, corrections, and marginal additions, it is possible that the manuscript is a so-called “foul paper”, whether of Shirley’s Traitor or not. The term “foul paper” has been defined by The Oxford Companion to the Book as “a draft MS of a work” (Suarez and Woudhuysen), but contemporary writers used the term to mean a range of similar but not identical things, including “dirty, scrappy, or befouled paper” and “loose, ad hoc, careless, or confused notes”. Prompted by the manuscript, Smith investigates this term in a companion piece to his edition (Smith 2016). He concludes that Melbourne is a particular kind of draft or foul paper, one which was rejected or otherwise abandoned for some reason, and its survival enables us to add an unstated but bibliographically implicit definition of “foul paper” to the list: that of a discarded draft, repurposed as scrap or waste paper. It therefore illuminates rejection as a rarely glimpsed aspect of the process of textual production.

Rather than use Melbourne uncritically as an exemplar for all early modern theatrical drafts, Smith urges that we should be careful to define its precise bibliographical nature as a discarded and repurposed manuscript, whose value was seen in its function as scrap paper rather than in its literary merit. This “found” manuscript can therefore help conceptualise the many dramatic documents now lost, but without which no play is possible.

For What It's Worth

The Melbourne Manuscript was discovered by Edward Saunders in 1985 at Melbourne Hall, Derbyshire. It had been used to wrap a packet of letters in the custody of Sir John Coke (1563–1644), a principal secretary of state under Charles I. It was advertised for sale as Webster's at its auction in London on June 20th, 1986. Auctioned at Bloomsbury Book Auctions, the manuscript was estimated to sell at £200,000-£400,000; a target which was unmet (Smith, 2017). Pryor explains that “When the archive was listed for the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts at the end of the last century it was docketed ‘Packet 3,’ and for some reason passed over in silence. It ended up in a box containing plans for the garden.” There is some uncertainty as to the exact nature of Packet 3’s contents. Pryor notes that the packet contained “correspondence by Coke dating between 1601 and 1630, and Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke’s household accounts for 1602–03”, but Smith – secretly hoping for a connection to the papers of Coke’s fellow Secretary of State, Edward Conway – found no evidence in the records of Coke’s correspondence that might offer more specific information. Given that Saunders found such miscellaneous material within the packet, the manuscript was probably used to wrap documents already within the Coke household, rather than deliberately grouped items being sent to Coke. As such, it seems unlikely that the contents of the packet would cast light on the manuscript’s provenance.

The play fragment was read through aloud by attendees of the Early Modern Interdisciplinary Seminar held at Clare College, Cambridge in November 2015, in advance of a research paper on the manuscript. Some attendees were skeptical of the two-hands claim.

Works Cited

Bawcutt, N.W. “The Assassination of Alessandro De’ Medici in Early Seventeenth-Century English Drama.” The Review of English Studies 56/225 (2005): 412–23. Beal, Peter, “James Shirley (1596–1666)”, CELM. Accessed September 22, 2019. Beal, Peter, “Papers Most Foul: A Lost Tragedy by John Webster?”, unpublished article commissioned by the Times Literary Supplement. Bentley, G.E. The Jacobean and Caroline Stage, 7 vols (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1941–68). Berger, Thomas L., and Sonia Massai (eds), Paratexts in English Printed Drama to 1642, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). Carter, John Stewart (ed.), James Shirley, The Traitor (London: Edward Arnold, 1965) Hammond, Anthony and Doreen Del Vecchio. “The Melbourne Manuscript and John Webster: A Reproduction and Transcript.” Studies in Bibliography 41 (1988): 1–32. Jackson, MacDonald P. “John Webster, James Shirley, and the Melbourne Manuscript.” In Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England, edited by S. P. Cerasano, (Cranbury, N.J.: Associated University Presses, 2006): 21-44. Pryor, Felix. “From Packet 3 to ‘The Duke of Florence’.” The Spectator, June 13, (1986). Shapiro, I.A. “letter.” Times Literary Supplement, July 4, (1986). Smith, Daniel Starza. “Unvolving the Mysteries of the Melbourne Manuscript.” Huntington Library Quarterly 79, no.4 (2017): 1–43. Smith, Daniel Starza. “Papers Most Foul: The Melbourne Manuscript and the ‘Foul Papers’ Debate.” In James Shirley and the Early Modern Theatre: New Critical Perspectives, edited by Barbara Ravelhofer, (London and New York: Routledge, 2016): 124-138. Suarez, Michael F., and H. R. Woudhuysen (eds), The Oxford Companion to the Book, 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Site created and maintained by Daniel Starza Smith and Clodagh Murphy, King's College London/Centre for Editing Lives and Letters UCL; updated 04 October 2019.