Osmond the Great Turk

Historical Records

Licencing

Sir John Astley, Master of the Revels (March 1622-July 1623) recorded the following in his office book:

Item 6 Sep. 1622, for perusing and allowing of a new play called Osmond the Great Turk, which Mr Hemmings and Mr Rice affirmed to me that Lord Chamberlain gave order to allow of it because I refused to allow it <?at> first, conteyning 22 leaves and a page--- Acted by the King’s players … 20s

(Bawcutt 137)

Title-Page (Wing 2nd ed., C582)

Two plays were published together thirty-five years later:

Two New PLAYES. / 1. The Fool would be a Favourit: / or, / The Discreet Lover. / 2. Osmond, the Great Turk: / or, / The Noble Servant. / As they have been often acted, / by the Queen’s Majeststy’s Ser- / vants, with great applause. / Written by / LODOWICK CARLELL, Gent. / LONDON, / Printed for Humphrey Moseley, and are to be / sold at his Shop, at the Prince’s Armes in / St. Paul’s Church-yard. 1657.

(ESTC)

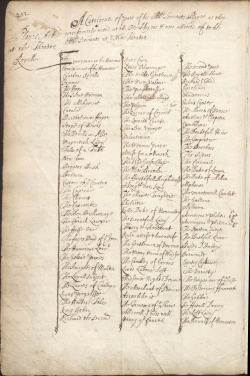

Lord Chamberlain's Department: Warrant Book 5/12

Included on p.213 in list of the plays allocated to Thomas Killigrew for performance at the Theatre Royal in 'A Catalogue of part of His Mates Servants playes as they were formerly acted at the Blackfryers & now allowed of to his Mates Servants at ye New Theatre' (c. 12 January 1668/9) is:

- ‘Osmond ye Great Turke’

|

|

National Archives, L.C. 5/12, p.212-13, reproduced by permission. (Click image to view larger version). See also Bentley 3.120, citing Nicoll 315-16.

Theatrical Provenance

The 1622 licence granted by the Master of the Revels at the second time of asking is the only evidence that a play of this title was owned by the King’s Men at this time; that the playwright is not identified is wholly unexceptional. The 1657 title-page for Lodowick Carlell’s play of the same title (for which his authorship is not disputed) indicates a different company: the Queen’s Men, who were active later, from 1637-42. This discrepancy, and the puzzling identicalness of the titles, is at the centre of the issue of whether the titles refer to two distinct plays or to the same one.

Probable Genre(s)

Tragedy (?) (Harbage); History/Contemporary politics.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

Samuel Chew pointed out that the treatment in the 1657 play of the fall of Constantinople in 1453 calls up the legend of ‘Irene’, the Greek captive with whom the victorious sultan falls in love. The Ottoman victory was seared into the Christian cultural memory, and playwrights exploited this knowledge, principally through the evocation of the predicament of the Christian maiden, who thus served as a metonym for the catastrophe. Moreover, in the sultan’s struggle to control his desire was offered a replaying of the Mars-Venus trope, which was ideally suited to the practicalities of playmaking. Thus as shorthand for 1453 it featured in a good number of plays, of which The Spanish Tragedy, the Tamburlaine plays, and Othello are the best known. Carlell’s is in fact the fullest dramatization of the legend: he was almost certainly influenced by the stage tradition, but he may have been the first to dramatize the event directly, the play beginning in the immediate aftermath of the Turks’ victory; the theme continued to be popular into the eighteenth century.

Carlell may also have drawn on Richard Knolles’ Generall Historie of the Turkes for the 1453 material, as Friederike Hahn suggests; if the extant play is that which Astley licensed in 1622, he would have learned of the assassination in May of Sultan Osman II from pamphlets such as A true and faithful relation of the death of Sultan Osman and The strangling and death of the great Turke, which were printed London in the summer of that year. In splicing together the 1453 tradition with the overthrow of the sultan in 1622 Carlell seems also to have been influenced by the Jacobean theatre’s exploration of female sexuality and psychology (see ‘Critical Commentary’).

References to the Play

None known beyond the Astley reference (and, if the play is considered extant, the 1657 title-page) cited above, and the 1668/9 warrant book.

Critical Commentary

Lodowick Carlell’s play has received surprisingly little attention despite the rise in interest in the ‘Turk play’ over the past decade or so. The play’s only modern editor, Allardyce Nicoll, accepts the 1657 title-page attribution and correspondingly dates the play to 1637-1642, which leaves the 1622 licence unexplained (ix-xii); he otherwise ignores the content of the play. Samuel Chew cites and agrees with Nicoll’s dating of Carlell's play and identifies the play as participating in a theatre narrative that called up the legend of ‘Irene’, a popular, western story about Sultan Mehmed II’s infatuation with a Christian captive following the fall of Constantinople in 1453 (488-89).

G. E. Bentley (3.119), unable to reconcile the company affiliation on the 1622 licence with the information on the 1657 title-page, concluded that the latter must be an error.

The few scholars to have gone into the matter all agree that the title of the extant 1657 play presents a bit of a puzzle: Osmond is not the ‘Great Turk’ – i.e. the sultan – but his servant. On the basis of this discrepancy E. E. Duncan-Jones contended that the extant play cannot be the play that was licensed in 1622, an argument challenged independently by Friederike Kahn and Mark Hutchings. Kahn takes Duncan-Jones’s point that a 1622 play would have alluded to the assassination earlier that year of Sultan Osman II as evidence in fact that the extant play and the title licensed in 1622 are one and the same, since Carlell’s play dramatizes the death of a sultan. Hutchings provides the fullest discussion of the play to date, showing how Carlell combined the traditional legend associated with the fall of Constantinople with the news that had recently reached London. However, Osmond the Great Turk is not quite the orthodox rendering we might expect. The Christian narrative that emerged following the fall of Constantinople was that the ‘Great Turk’ would eventually be overthrown: the events of 1622 superficially offered solace and hope to Christians so desirous of that end, but the play does not celebrate the revolt and in fact shows the rebellious pashas to be treasonous. The hero of the play is the noble servant of the title, who kills the assassins; most remarkable, however, is the strikingly ‘Jacobean’ treatment of Despina, the Irene figure. Far from being a chaste victim she is in the mould of The Changeling’s Beatrice-Joanna or Bianca of Women Beware Women, fully aware of the power she has over the besotted sultan, which she exploits to the full.

For What It's Worth

The arguments in favour of identifying the extant play, printed in 1657, with a play of the same title licensed in 1622 are stronger than the objections against. There is no reason to doubt the veracity of the licence signed off by Astley; conversely, title-page information is sometimes of doubtful authenticity. Bentley is surely right that ‘it seems highly improbable that the Queen’s Men should have taken a play away from the most successful and influential troupe of the time’ (3.120), and his conclusion that ‘an error in the 1657 title-page’ is the most likely explanation is further supported by what we know about Carlell’s career, and the contextual information through which we can with some confidence associate the 1622 licence and the 1657 text.

Lodowick Carlell wrote exclusively for the King’s Men. He was young, only twenty, in 1622, and his plays tend to be dated rather later, to the Caroline period. But his age is not a disqualifier. Indeed, Bentley has suggested a date of 1625 for The Fool Who Would Be a Favourite, the companion play printed with Osmond the Great Turk, while Irwin Smith places both plays in 1622 (Bentley, 3.117; Smith 216-17). Firm evidence places him at court at this time. Bentley cites a letter written by the Marquis of Buckingham to Lord Cranfield on 11 November 1621 in which, with reference to Carlell, he remarks that ‘the king favours him’, and Bentley further points out that the Lord Chamberlain’s intervention over the licensing of the play, overruling the Master of the Revels, is plainly suggestive of connections and influence with courtiers of high rank (120-1).

Such connections may also help explain the origins of the problems the 1622 play faced. That there were problems is evident from Astley’s note. Matching the extant 1657 text to 1622 makes a good deal of sense when we consider the subject matter and the court context. For all that a play about the toppling of a Turkish sultan might sit not altogether uncomfortably with the residual cultural purchase of attitudes fomented since 1453, it was also, and more significantly, a play about regicide. The king’s sensitivity about such matters was understandable, given the Stuarts’ own history and indeed recent examples, notably the murder of Henri IV of France in 1610. But there were also possible domestic correspondences as well. As Bentley suggests, a passage in the play could have been interpreted as ‘a reference to James’s difficulties in raising benevolences in 1622’ (3.121). Whether the portrayal of a favourite was also sensitive, given the general unpopularity of the court and in particular James’s protection of first Robert Carr and latterly Buckingham, is moot, but it must be considered a possibility. Carr, along with his wife Frances Howard (the marriage having been promoted by the king himself in ensuring her divorce from the earl of Essex) had been found guilty of poisoning Sir Thomas Overbury; while their accomplices had been executed they had been sent to the Tower, from where they were released in January 1622. Although the text of the 1657 play is largely unsympathetic to the notion of regicide and extols both the loyalty of the noble servant and the succession with which the play concludes, the subject matter alone may have been sufficient to alarm Astley.

Nonetheless, if the sultan’s remark to the effect that in Christian countries subjects paid taxes to the monarch to ensure their safety was considered risky we only know of its existence because it remains in the text that was printed, thirty-five years later. Whether the Lord Chamberlain’s intervention protected the play in its entirety, or some changes were requested, at some stage in the licensing process, is unclear. At any rate the text does appear to be problematic at one point, the close of the second act. Bentley and Richard Dutton draw attention to a signal within of ‘Fire’, which is followed by an incongruous entrance by a character already on stage; with this the Act ends. Bentley describes this as ‘a derangement which certainly indicates the deletion of something and possibly of lines which Astley found objectionable’ (3.121). However, a more prosaic explanation may lie in the setting of the text for printing. If the entrance with which Act 2 concludes is moved to the beginning of the third Act then sense is restored: it may well be that the manuscript with which the compositor worked thirty-five years after Astley approved the play was deficient or the printing was at fault.

The interest that the play attributed to Lodowick Carlell on the 1657 title-page has aroused is almost entirely confined to the nature of its licensing in 1622. Scholars no longer doubt that the later, extant text is the play Astley licensed, though the specific circumstances and relations between the principal figures remain conjectural. However, scholars have ignored crucial evidence unearthed by Nicoll and included in his History of Restoration Drama and which Bentley cites, the significance of which was apparently (and surprisingly) missed by both scholars. This is the third item in the documents given in the ‘Historical Records’ section. Nicoll, quoted here by Bentley, notes a reference in 1668/9 ‘in “A Catalogue of part of His Ma[jesty’s] Servants Playes as they were formerly acted at the Blackfryers & now allowed of to his Ma[Jesty’s] Servants at ye New Theatre” occurs the title ‘Osmond ye Great Turke’ (Nicoll, 315-6; Bentley 3.120). The significance of this is that a play with this title, attributed to the King’s Men, existed in 1668/9; and since this attribution contradicts the company provenance of the 1657 title-page, where it is attributed to the Queen’s Men, in all likelihood the extant King’s Men play was indeed that licensed by Sir John Astley in 1622. It is surely highly improbable that this reference could be to the 1622 play but not to Carlell’s: such a scenario would require that the 1657 play is a different play from that recorded in a catalogue ten years later which, other than the 1622 licence, has left no further trace of any kind. Osmond the Great Turk is almost certainly then not a lost play but the (identical) title for a play published rather later, and almost certainly performed, like Carlell’s other plays, by the King’s Men.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Mark Hutchings, University of Reading; 27 Sept 2015.