King of England's Son and the King of Scotland's Daughter

NB. the date is conjectural; in the absence of new information, the LPD follows Wiggins's approximation of the date for simplicity.

Historical Records

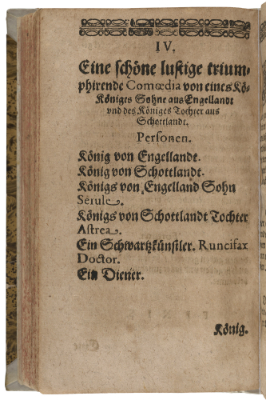

Eine schöne lustige triumphirende Comoedia von eines Königes Sohn auß Engellandt vnd des Königes Tochter auß Schottlandt, a German redaction of what is evidently a lost English play, was published in 1620 (probably at Leipzig) in an octavo volume edited by Friedrich Menius (1593-1659): Engelische Comedien und Tragedien.

The Lost Plays Database has sponsored the digitisation of the full German play (from Folger PR1246.G5 E59 Cage) and is preparing an English translation:

|

|

| Engelische Comedien und Tragedien, sig.R6v Folger Shakespeare Library (CC BY-SA 4.0 licence) |

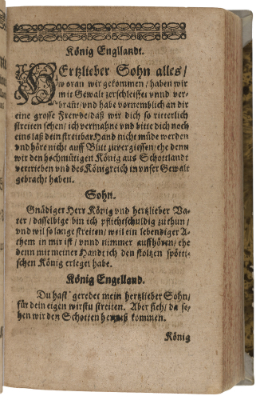

Engelische Comedien und Tragedien, sig.R7r Folger Shakespeare Library (CC BY-SA 4.0 licence) |

Click images to view larger versions and view the entire play in full here.

(English translation forthcoming.)

Theatrical Provenance

The English provenance remains unknown, but the German version was performed at the court of Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse, in Kassel in March 1607 (a court official’s letter relates that the players were dissatisfied with their payment; see Schlueter, "Across the narrow sea", 237-38), was revived at the Court of Saxony in Dresden in 1626, and again, this time as a puppet play, in Danzig in 1668 (see Wiggins #1102).

Probable Genre(s)

Comedy.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

The play is premised on the King of England sending his son (Serule) to fight the King of Scotland but instead falling in love with the Scottish king’s daughter (Astrea). The lovers negotiate a year’s truce, during which time they hope to engineer a more lasting peace. Serule, however, is barred from engaging with the Scots. To overcome this injunction, he places a spy in the household of the Scottish king’s advisor, the magician Runcifax/Barabas, and manages to enter the Scottish court himself by adopting the disguise of a fool. The magician’s magic mirror reveals that the princess will marry the fool, news of which enrages the Scottish king, but Serule escapes – only to return disguised this time as a Moor. This plan, too, is thwarted and Serule flees with the now disguised Astrea. He is captured by the Scots, and she by the English; a battle ensues and tragedy is narrowly avoided when Serule is poisoned but only with a sleeping potion. A kiss from Astrea revives him and a royal wedding is planned. The German play also contains what Wiggins describes as the “relic of a sub-plot in the original” involving magical transportation, the magician’s servant, a Sultan, and the abduction of the Princess of Spain (#1112).

References to the Play

Noting that this is a play "in which the King of Scotland is cast as the comic parent unsympathetic to his daughter's love-life, and is shown consorting with a black magician and apparently poisoning the English Prince", Wiggins (#1111) thought that the reference to an anti-Scots play by George Nicholson in his letter to William Cecil, Lord Burghley (15 April 1598) might conceivably be to "The King of England's Son and the King of Scotland's Daughter".

Schlueter ("An illustration") has suggested that a watercolour painting dated to c.1605/6, in the album amicorum or friendship book of Franz Hartmann (British Library Egerton MS 1222, fol.25) might depict "a troupe of travelling [English] players" (194), and further suggests that it might be a visual reference to "The King of England's Son and the King of Scotland's Daughter": "[i]f the Hartmann painting is of a particular troupe, could the player in red have been the captive princess, the player with the falcon the captive prince?" (197). The image has been digitised by the British Library:

British Library Egerton MS 1222, "Album of Franz Hartmann" (1597–1617), originally digitised for the BL's Discovering Literature: Shakespeare project and reproduced in accordance with its reuse policy. Clicking the image will take you to the full-sized image on the British Library's site.

Critical Commentary

Drábek and Katritzky conclude that the play is “without an obviously identifiable source”, but liken it to a “generic group of romantic disguise plays” including Mucedorus, which they hint is a close relative of sorts (1531).

McInnis, working with Bastian's translation of the play into modern English, notes that although the play lacks an obvious source, it nevertheless draws on numerous tropes and conventions from commercial drama of the London theatres, and reads it against "Shakespeare’s depictions of troubled or distracted youth in the 1590s" (227). He provides a detailed plot summary, focusing on parallels with the prodigal son legend (explicitly in another lost English / extant German play published in the 1620 volume, and implicitly in the figure of Shakespeare's Prince Hal) and the star-crossed lovers Romeo and Juliet (the German version of which was also performed on the Continent by travelling English players), as well as the broader echoes of Marlowe's Faustus and Jew of Malta, Greene's Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay (in the German play's use of a magic mirror that resembles Bacon's prospective glass), and Dekker's Old Fortunatus (itself translated into German and published in this 1620 volume), in terms of magical transportation.

He notes that "internal evidence suggests cutting and adapting, and thus a close relationship between the German text and the

lost English original. The German version has been trimmed for performance, whereas the longer English text evidently included Astrea’s two suitors, the subplot of the abducted Spanish princess and the Sultan, and gave the name “Runcifax” to the magician (who becomes known instead as “Barrabas” in the German playtext). Redundant stage directions in the German may constitute editorial intervention by Menius, but may also suggest staging possibilities and episodes cut from the lost English version, thereby implying that the German text is relatively close to its precursor (rather than being substantially rewritten or altogether adapted)" (226).

Schlueter has suggested an alternative to the German play being a redaction of a lost English original: "[b]ecause there is no known English source play; because the names of two of the characters — Morian and Barrabas — are also the names of characters, respectively, in the Titus play in the 1620 collection and Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, which was also performed in Germany; and because the play is compact, requiring only six actors, one wonders whether the players themselves might have contrived it” (“Across the Narrow Sea,” 237).

For What It's Worth

The 1620 volume

The Engelische Comedien und Tragedien volume includes eight plays plus other entertainments, including:

• Esther and Haman (“Comoedia Von der Konigin Esther vnd hoffertigen Haman”)

• The Prodigal Son (“Comedia. Von dem verlornen Sohn in welchen die Verzweiffelung vnd Hoffnung gar artig introducirt warden”)

• Fortunatus (“Comoedia Von Fortunato vnd seinem Seckel vnd Wunschhutlein, Darinnen erstlich drey verstorbenen Seelen als Geister, darnach die Tugenden vnd Schande eingefiihret warden”)

• The King of England’s Son and The King of Scotland’s Daughter (“Eine schöne lustige triumphirende Comoedia von eines Königes Sohn auß Engellandt vnd des Königes Tochter auß Schottlandt”)

• Sidonia and Theagenes (“Eine Kurtzweilige lustige Comoedia von Sidonia vnd Theagene”)

• Nobody and Somebody (“Eine schone luftige Comoedia von Jemand vnd Niemandt”)

• Julio and Hyppolita (“Tragaedia, Von Julio vnd Hyppolita”); and

• Titus Andronicus (“Eine sehr klagliche Tragaedia von Tito Andronico etc”).

Of these plays, only Sidonia and Theagenes is of German origin, and has no known English counterpart. Esther and Haman appears to be related to the lost "Hester and Ahasuerus" play of the Chamberlain's repertory at Newington Butts; Fortunatus is a version of Dekker's Old Fortunatus (1600) and Nobody and Somebody is a version of the English play by that name (Anon., 1606); Titus Andronicus corresponds in some way to Shakespeare's play, and Julio and Hyppolita corresponds to Two Gentlemen of Verona.

Runcifax and Barrabas

The necromancer is listed as “Runcifax” in the list of dramatis personae, but the name is not used in the text itself; evidence that the playtext has undergone some significant alterations. As Albert Cohn notes, the name “Runcifax” “strongly reminds us of ‘Runcifall the Devil,’ in [Jacob] Ayrer’s ‘Beautiful Sidea’ [c.1595],” a play with analogies to Shakespeare’s The Tempest (Cohn, Shakespeare in Germany, cx). The name which does appear for the necromancer in the text, “Barabbas”, instantly recalls Marlowe's Jew of Malta, but would also have been familiar to early modern audiences as the name of the prisoner whom Pontius Pilate released instead of Jesus (see, e.g., Mark 15:6–15).

Staging Blackness

At one point, the prince, eager to see the princess but needing a disguise to gain access, “puts on a black dress and ties a gauze onto his face” and disguises himself as a Moor, then attempts to sell “three precious jewels” to the king.

On the English stage’s use of black gauze to simulate racial alterity, see Ian Smith, “Othello’s Black Handkerchief,” Shakespeare Quarterly 64.1 (2013): 1–25, esp. 10ff. Although Smith finds evidence of racial alterity being depicted through the use of material (“pleasance,” a fine, gauzelike fabric) in court entertainments in England, and infers Shakespeare’s familiarity with such practices even at a time when the application of cosmetics had advanced and were widely used in public theaters to simulate blackness, he does not present explicit evidence of public-theater use of textile corporeality. Instead, he observes that “the explicitly material forms of racial impersonation derived from the court tradition significantly influenced [Shakespeare’s] conceptualizations of race at specific moments” and that “For Shakespeare … the technique of the material body coexisted with that of skin painting” (12, 13). Smith accordingly suggests that “Rather than posit a narrative of increasing technical improvements in racial impersonation, the evidence suggests simultaneous imitation practices where the textile body, whether as an immediately tangible stage presence or as an item remembered from earlier performances, reinforces and materializes blackness within the economy of early modern racial discourse” (13).

The present use of gauze in a lost English play of c.1598 seems to provide new evidence to support Smith’s claims of the currency of this textile use in public theaters.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated 27 July 2020.