Jeweller of Amsterdam

Fletcher, Field, & Massinger (1616)

Historical Records

Stationers' Register

08 April 1654 (S.R.II, 1.445)

| Master Mosely. | Entred . . . A play called, The Jeweller of Amsterdam, or the Hague. | |

| By Mr John Flesher, Nathan Field & Phillip Massinger . . Vjd | ||

Music

Wiggins notes that "some music which may have been associated with the play was included in John Adson's Courtly Masquing Airs, no. 15, sig. B1v". That music is not identified other than by its numeric designation, however the same music appears as item 91 in British Library Add. MS. 10444 (c.1624), this time under the title "Van Welly" (Wiggins #1804), and might therefore pertain to the murdered protagonist of the lost play (see sources below, but see also Critical Commentary).

|

|

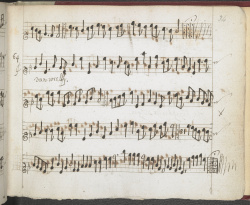

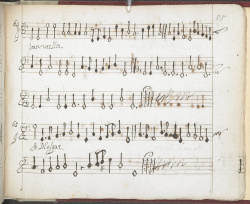

| BL Add. MS 10444 fo.34r. | BL Add. MS 10444 fo.85r. |

British Library Add. MS. 10444, reproduced with permission

This music has been professionally recorded for the Lost Plays Database by Ludovico's Band, using modern copies of historical instruments (Marshall McGuire - triple harp, Shane Lestideau - baroque violin, Samantha Cohen - theorbo, and Ruth Wilkinson - viola da gamba). Recorded in the Salon, Melbourne Recital Centre on December 15, 2016 (sound engineer: Alex Stinson). Press play below to hear this musical fragment:

Html5mediator: error loading file:"Ludovico\u0026#039;s_Band_-_van_Weelly_48k-16b.mp3"

Theatrical Provenance

King's Men.

Probable Genre(s)

Tragedy (Harbage); true crime.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

The subject matter of this lost play is almost certainly the murder of John de Wely, a jeweller in Amsterdam, who was robbed and killed by two men associated with the court of Maurice, Prince of Orange at the Hague. The murderers, John de Paris and John de Vigne (or "de la Vigne"), knowing that de Wely had brought precious jewels to the prince, coaxed him into the Chamber and there shot, stabbed, and finally strangled him to death.

A short pamphlet claiming to publish the murderers' confessions was issued later that same year (1616), and could have furnished the playwrights with material for their tragedy:

Anon. True recitall of the confession of the two murderers John de Paris, and Iohn de la Vigne touching the horrible murder committed vpon the person of Mr. Iohn De Wely, merchant-ieweller of Amsterdam : together with the sentence giuen against them at the court of Holland, at the Hage, the 16. day of May, 1616, and executed vpon them the same day. [S.l. : T. Snodham for N. Bourne, 1616]

Synopsis

The True recitall begins with the confession (extracted on the rack) of John de Paris, Gentleman of the Chamber to Prince Maurcie de Nassau and “present prisoner in the Court of Holland” (sig.A3), that he killed John de Wely, Merchant Jeweller of Amsterdam in March, 1616. De Wely had reportedly shown the prince “a certaine most precious hat-band beset with Diamonds”; the prince had expressed interest in the item, so de Wely asked de Paris to take custody of the item to facilitate the prince’s next viewing of it. De Paris led de Wely into the Chamber and showed him a trunk which was to be used for safekeeping of the hat-band. Although de Paris did show it to the prince the next day, he also showed it to “some of his friends attending his Excellencies returne from the Church”, and after returning the hat-band to the jeweller, de Paris conferred with John de Vigne, a soldier in the prince’s Guard, “saying vnto him, that who so could turne vp the heeles of such a man, and seaze on his Iewels, should haue enough for all his life time”. The men agreed that if they could get the jeweller back into the same Chamber where the hat-band had been stored, “they would kill him, and possesse themselues of hie Iewels, assigning for this businesse the very same day”, which (being a Sunday) would provide cover for their crime in the form of the noise of dancing associated with the feast planned by the prince (sig.A3v).

De Wely was accordingly invited to the feast by de Paris, even attempting to deflect suspicion by recommending that the jeweller not bring his valuables with him for fear of pickpockets, but de Wely ultimately did not attend the feast and the first plan was thwarted (sigsA3v-A4).

On the Monday, the conspirators hatched a new plan, hoping to bring the jeweller again to court with his jewels, where they would “pistol him least hee should speake or make any noyse”. If the prince were at Court, de Paris would hurry to the Armoury after the gunshot and “say that he had shot at one of his armours”, thus concealing their crime (sig.A4). The jeweller came to court demanding to speak to the prince; de Paris suggested he come back after dinner, with his jewels, and “shut the wooden windows of his Chamber to be the lesse seene” (sig.A4). De Vigne was placed in the Chamber “in a readinesse”; de Wely returned to Court around 3pm, and was led into the dining room and then under the arras, so as to pass to the Chamber without being seen (sig.A4v). De Paris conversed with the jeweller for some time about the precious stones, before taking a pistol out of the chamber (in front of the jeweller!) and taking it to the Armoury to give to de Vigne. De Paris charged a pistol with only a little gunpowder, in an attempt to reduce the noise that it would make when fired; de Vigne requested a poniard “to make altogether an end of him” (sig.A4v). De Paris returned to the Chamber to fetch a key and obtain a poniard for de Vigne, who subsequently entered the chamber as if to escort the jeweller to see the prince (who had in fact departed by coach in the meantime), and – after a sign from de Paris – “came behind the said Ieweller, & with his Pistoll shot him through the head, the bullet entring a little aboue one of his eares, came out behind the other, and struck against the walls” (sig.B). The shot did not kill the jeweller though, whose “eyes turned and stared in his head like a maddemans”. De Paris quickly left the Chamber to ascertain whether anyone had heard the crime; satisfied that they had not, he returned, finding that de Vigne had flung the jeweller to the ground and stabbed him twice. De Paris then took two silk ribbons, tied them together, and strangled the jeweller and removed the jewels from his pocket (sig.B).

The murderers placed the body in a corner, elevating the head to minimise the spilling of blood, covered it with a tablecloth to hide it from sight, then sought a boat with which to transport the body to the fields for burial. Being unable to find a boat, they instead resolved to thrust the body into an ash-dunghill at the back of the Court later that day, “then went both of them with another man to drinke three or foure pots of wine in the Towne” in order to create an alibi (sig.Bv). That night after supper they dug the hole in the dunghill, bound the body (pulling “his hat ouer his eares that hee might bleede the lesse”), removed their shoes and took a circuitous route to avoid detection, and conveyed the body to its burial place (sig.B2). They took care to hang coats over the chamber window so that the candlelight they needed would not be observed, and they wiped up the spilled blood and burned the napkin and ribbons used to bind the jeweller after completing their task. The men cleaned the shovels used for digging the grave and then washed themselves at the pump in the stableyard. The jewels were hidden by de Paris in a “little coser” (a casket or chest), then in earthen flower pots in the garden and subsequently buried in his cellar (sigs.B2r-v).

The criminal activity did not end there, however; de Paris, learning that the prince’s Notary had a “great summe of money” hidden around his home, began to plan the next adventure. Drinking at a tavern with de Vigne and a man named Goussepin, and seeing said Notary overcome with drink, de Paris and de Vigne conspire. De Vigne lies in bed with the passed out Notary, steals his keys, passes them to de Paris, who ransacks the Notary’s chamber and returns to court with the loot. Unfortunately he runs into Goussepin there, who had not known about the enterprise until he spied money falling out of the bulging bags of cash being carried by de Paris. The keys are returned to the Notary’s pocket, the Notary returned to his own room to sleep, and a fruitless attempt is made to buy Goussepin’s silence. The crimes are discovered, and the murderers sentenced to execution.

(The events are then retold from the perspective of John de Vigne).

References to the Play

Information welcome.

Critical Commentary

Bentley assumes the playwrights responded swiftly to news of the murder: "Presumably Fletcher, Massinger, and Field had their play ready while the events in the Netherlands were still fresh in the public mind, as Fletcher and Massinger did two or three years later in the very similar circumstances of Sir John Van Olden Barnavelt (3.351).

John P. Cutts suggested that the music titled "Van Welly" "[p]robably refers to Vandelle Welde, a Dutch picture dealer who came to court c. 1610-12" (197), and thus may not refer to the jeweller of Amsterdam.

Wiggins (#1804) notes that "[w]hat is distinctive about the story is the fact that the murder takes place within the very precincts of the Dutch court, in the shadow of the Prince's own movements. It follows that Prince Maurice must have featured in the play in some way; but since Sir George Buc was dubious about his representation on stage three years later in Sir John van Oldenbarnevelt ..., it seems likely that similar reservations would have kept Maurice only an off-stage presence in The Jeweller of Amsterdam."

Stephenson claims that Moseley, whose publications favoured Royalist literature during the Interregnum, made the conscious decision not to print an edition of "The Jeweller of Amsterdam." Claiming that "Moseley did not omit Jeweller from the 1647 folio because he had no knowledge of it" (33), Stephenson suggests that Moseley acquired a complete set of plays authored or co-authored by Fletcher from the actors of the King's Men and declined to print "Jeweller" based on its depiction of Maurice, Prince of Orange, both an ally of King James and a political figure who might be compared to James. While conceding that "the pamphlet does not specifically cast Orange in a bad light," Stephenson argues that "the potential for unfortunate interpretation must have been everywhere in a play based on that pamphlet": "it would be noted that Orange kept scoundrels like de Paris and de Vigne (the two murderers) among his retinue; he must have been depicted (and perhaps seen or heard) to be eating, drinking, and making merry while a murder is plotted nearby; and even his taste for flashy and expensive jewelry might have cast him in an unflattering light. Finally, the swiftness and mercilessness of the sentence could have been seen as harsh" (32). In Stephenson's account, by entering the play in the Stationers' Register but not printing an edition, Moseley "prevented others from doing so by retaining the rights to print it for himself" (33).

For What It's Worth

The incident that likely furnished the subject matter of the lost play was subsequently remembered as an example of the justness of Prince Maurice of Nassau, who chose to have the murderers gruesomely executed as an example to others rather than attempt to cover up their crime in case it reflected badly on him by association (both men being in his employment at Court):

The Prince Elector Palatine, and Maurice Prince of Orange, were made Knights of the Garter, Lodowick Count of Orange being Maurice's Deputy; and Prince Maurice took it as a great honour to be admitted into the fraternity of that Order, and wore it constantly: Till afterwards, some Villains at the Hague, that met the Reward of their Demerit (one of them a French man, being Groom of the Princes Chamber) robbed a Ieweller of Amsterdam, that brought Iewels to the Prince, this Groom tempting him into his Chamber to see some Iewelr, and there with his Confederates they strangled the man with one of the Princes blew Ribonds; which being after discovered, the Prince would never suffer so fatal an Instrument to come about his Neck.

(Arthur Wilson,History of Great Britain [1653], 64)

But to return to the character of Prince Maurice, he was naturally good and just, and died with the reputation of an exemplary Honesty; to show that he deserved this character, I need only relate the following Story. Two of his Domestics who were Frenchmen, one called Iohn de Paris, who waited upon him in his Chamber, the other one of his Halberdeers, named Iohn de la Vigne, having assassinated a Jeweller of Amsterdam, who had Stones of a great Value, which he would have sold the Prince; he was so far from protecting them, (as several Persons of Quality would have thought it concerned their Honor to do) that on the contrary, he himself prosecuted the Actors of so inhumane a Butchery, and made them both be broke alive upon the Wheel.

(Louis Aubery du Maurier, The lives of all the princes of Orange [1693], 155)

Curiously, a John de Weely, "Citizen and Merchant of Amsterdam, a very curteous and obliging person", was also notable for apparently having sold a rare bird of paradise ("with its Feet still remaining to it") to the Emperor in June 1605. (Ray 96; see also Purchas, book 5, ch.12, p430).

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated 06 January 2017.