Henry II

Davenport, Robert (and Shakespeare?) (unknown date)

Historical Records

Stationers' Register

09 September 1653 (S.R.II, 1.429 CLIO)

- Master Mosely Entred also . . . the severall playes following . . xxs vjd

- ...

- Henry the first, & Hen: the 2d, by Shakespeare & Davenport.

Theatrical Provenance

King's?

Probable Genre(s)

History (Harbage, Annals); Historical romance (Harbage, "Palimpsest" 318).

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

Henry II, king of England (1133–1189) is clearly meant by the title of this lost play. Succession negotiations had been underway since the 1140s, but Henry eventually succeeded King Stephen and acceded the throne in 1154.

Harbage proposes the ballad, "The Deathe of Faire Rosamond", which appeared in Deloney's Strange Histories (1607), as a likely source for Davenport ("Palimpsest" 313). His suggestion depends on his argument that Mountfort's Henry the Second, King of England; With The Death of Rosamond (1693) is a palimpsest containing traces of the lost "Henry II" play. He finds linguistic parallels between the 1693 play and the ballad to support his case for Strange Histories as a source (313). He also suggests that Davenport was indebted to Drayton's England's Heroical Epistles as republished in 1619, containing the exchange between Henry II and Rosamond ("Palimpsest" 317), but stops short of calling this a "source".

Deloney, Strange Histories

Deloney's ballad narrates the tension between Queen Elinor and Henry's lover, the fair Rosamond, explaining that Henry built a labyrinthine fortified bower at Woodstock to protect Rosamond. When Henry's son waged war against him, Henry took leave of Rosamond to fight in France. She faints upon hearing of his imminent departure, then pleads to go with him:

- But sith your Grace in forraine coastes,

- among your foes vnkind,

- Must go to hazard life and limme,

- why should I stay behind?

- Nay rather let me like a Page

- your Shield and Target beare,

- That on my breast that blow may light,

- which should annoy you there.

- O let me in your royall Tent,

- prepare your Bed at night,

- And with sweete Bathes refresh your Grace,

- at your returne from fight,

- So I your presence may enioy... (Deloney 1612 edn, sig.A4v; EEBO-TCP open access)

Henry convinces Rosamond to stay home in the bower under the guardianship of a knight, Sir Thomas, then takes his leave. In his absence, Queen Elinor lures Sir Thomas out of the bower, wounds him, and using his clue of thread to navigate the labyrinth, locates Rosamond within its many rooms and doors. The queen, though temporarily struck by Rosamond's beauty, orders her out of her costly robes and instructs her to take poison. Rosamond kneels, asks for pardon and pleads for banishment or cloistered life rather than death. The queen does not relent though, and Rosamond drinks the offered poison. Her body is buried at Godstow near Oxford.

Drayton, England's Heroical Epistles

Michael Drayton's England's Heroical Epistles (1603, rpt. 1619) includes a letter from "Rosamond to King Henrie the second" (EEBO-TCP, open access) and the matching letter of "Henry to Rosamond" (EEBO-TCP, open access):

The Argument.

Henry the second of that name, King of England, the sonne of Geffrey Plantaginet, Earle of Aniou, and Maude the Em∣presse, hauing by long sute and princely gifts, wonne (to his vnlawfull desire) faire Rosamond, the daughter of the Lord VValter Clyfford, and to auoyde the danger of Ellinor his iealous Queene, had caused a Labyrinth to be made within his Pallace at VVoodstocke, in the center whereof, he had lod∣ged his beauteous paramore. VVhilst the King is absent in his warres in Normandie, this poore distressed Lady, inclosed in this solitarie place, tutcht with remorse of conscience, writes vnto the King of her distresse and miserable estate, vrging him by all meanes and perswasions, to cleere himselfe of this infamie, and her of the griefe of minde, by taking away her wretched life. (sig.B)

Rosamond to King Henrie the second:

Rosamond writes to lament her involvement with Henry, blaming him for seducing her ("VVhy on a womans frailtie would'st thou lay / This subtile plot, mine honour to betray?" [fol.1v), and ruing the constant reminder in the form of their names "Cut in the glasse with Henries Diamond" in the window pane of her room (fol.2). In the context of her captivity in the purpose-built bower, she elaborates on the labyrinth metaphor, identifying herself as monstrous by implication:

- VVell knew'st thou what a monster I would bee

- vvhen thou didst build this Labyrinth for mee,

- vvhose strange Meanders turning euery way,

- Be like the course wherein my youth did stray;

- Onely a Clue to guide me out and in,

- But yet still walke I, circuler in sin. (fol.2v)

She recounts how her maid, passing the time with her, had noticed a portrait of the Roman Lucrece and inquired why she had killed herself; Rosamond, ashamed of her own lack of chastity, breaks down and cannot answer. She proceeds to liken herself to fish in the river, having foolishly taken the bait they're innately suspicious of, to her shame: "Rose of the world, so doth import my name, Shame of the world, my life hath made the same" (fol.3). Finally, taking inspiration from an engraved casked Henry had given her, she likens herself to Jove's love Io, transformed into a beast by her love (fol.4), and begs to die.

In his response, Henry (at war in France) relates how he eagerly awaited Rosamond's letter, but was confused and dismayed by its content, perceiving himself besieged on two fronts: "Am I at home pursu'd with priuate hate, / And warre comes raging to my Pallace gate?" (fol.5v). He bemoans his fortune and claims he would endure any number of hardships if only he continued to have Rosamond as his comfort (fol.6). He offers to distance himself from his regal identity (in a passage that has some analogy with the meditations on "names" in Romeo and Juliet) if his name is what offends Rosamond ("If't be my name that doth thee so offend, / No more my selfe shall be mine owne names friend", fol.7), and predicts that her name will become a byword for hope and succour:

- with the very sweetnes of that name,

- Lyons and Tygers, men shall learne to tame.

- The carefull mother from her pensiue brest

- vvith Rosamond shall bring her babe to rest;

- The little birds, (by mens continuall sonnd)

- Shall learne to speake, and prattle Rosamond,

- And when in Aprill they begin to sing,

- vvith Rosamond shall welcome in the spring;

- And she in whom all rarities are found,

- Shall still be sayd to be a Rosamond. (fol.7v)

He concludes by attempting to defuse her negative, monstrous implications of the labyrinthine bower by reminding her that he built it "[t]o lodge thee safe from iealous Ellenor" (fol.8), and by reinforcing the liebestod-like nature of his plight: "My campe resounds with fearefull shocks of war, / Yet in my breast the worser conflicts are..." (fol.8).

There is, of course, the possibility that the lost "Henry II" play (if it ever existed) was concerned not with Henry and Rosamond's love story, but with the conflict between court and church, and the tension between Henry II and Thomas a Beckett, whose friendship with Henry soured shortly after his transition from Chancellor to Archbishop of Canterbury, and whose death was widely blamed on Henry's notorious question, "Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?". Drayton's "Notes of the Chronicle Historie", for example, mention that: "King Henry the second, the first Plantaginet, accused for the death of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterburie, slaine in the Cathedrall Church, was accursed by Pope Alexander, although hee vrg'd sufficient proofe of his innocencie in the same, and offered to take vpon him any pennance, so he might escape the curse and interdiction of the Realme" (fol.8v).

References to the Play

Information welcome.

Critical Commentary

In the context of Moseley's entries, Gary Taylor refers to "Henry I" and "Henry II" as if a single play: "The 1653 entry also attributes to Shakespeare The Merry Devil of Edmonton (as did Charles I), and to Shakespeare and Davenport the lost Henry the First and Henry the Second, which Davenport wrote or adapted in the 1620s..." (20, n43).

Harbage ("Palimpsest") points out that "[s]ince the long reign of King Stephen intervened between those of the two Henrys, Henry the First and Henry the Second seems an extremely unlikely title for a play; and as Moseley in 1653 was saving fees by entering two plays as one, it is fairly obvious that he was doing so in the present instance". Harbage is less sceptical than Bentley about the authenticity of Warburton's list of play manuscripts, deducing from Warburton's reference only to "Henry ye 1st" that "the Henry the Second manuscript had evidently become separated from its fellow" (310). He further argues that the play "may not be totally lost", and claims that Henry the Second, King of England; With The Death of Rosamond. A Tragedy. Acted at the Theatre Royal, By Their Majesties Servants (1693), a play usually associated with the actor William Mountfort (but not necessarily of his authorship) is "a stage version of 'Shakespeare and Davenport's' Henry the Second" (311). (He does add the caveat, "I do not expect others to share fully in my belief", 318). He proceeds to note the "interesting coincidence" of Drayton's Heroical Epistles containing the stories of Rosamond and Henry II, King John and Matilda, and Queen Isabella and Mortimer --- the subjects (respectively) of Henry the Second (1693), Davenport's King John and Matilda, and Edward the Third (1691). Harbage provocatively asks:

Does it not seem likely that Davenport, acting upon the suggestion of the volume of 1619 [of Drayton's poems], embarked upon the creation of a series of neo-chronicles--centring upon the loves of the English kings rather than upon their martial exploits...? ("Palimpsest" 317)

Harbage follows this suggestion by observing a parallel between Davenport's King John and Matilda and Drayton's The Legend of Matilda (in order to establish Davenport's debt to Drayton more generally); in so doing, he notes "how in mentioning Henry II Davenport reveals what aspect of this king's career most engages his attention" --- referring to the line, "Henry the Wedlock-breaker" (318). He thus suggests the subject matter of the "Henry II" play by Davenport: "Davenport is thinking not of Henry the reformer, the opponent

of Becket, the conqueror of Ireland, but of Henry the Wedlock-breaker the lover of the Fair Rosamond" (318).

For What It's Worth

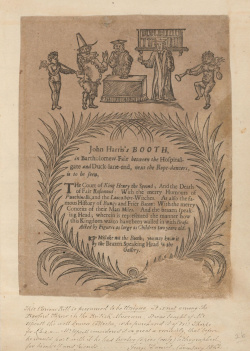

An undated playbill associated with the puppeteer John Harris (fl. 1690-1723), announces that audiences can see "Figures as large as Children two years old" perform the "Court of King Henry the Second; And the Death of Fair Rosamund" at the booth with the "Brazen Speaking Head' in Bartholomew Fair:

TS 555.1, Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, via Wikimedia.

Given the dates at which Harris flourished, the playbill's reference to Henry II may refer to a puppet version of Mountfort's play; to an original puppet piece independently derived from any of the available sources; or indeed, to a version of the lost play. The presence of a version of Greene's Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay in the advertisement offers some slight encouragement for this final possibility: Greene's play dates to c.1589 (Wiggins #822) and the lost "Henry II" is usually dated to 1624. The reference to the Lancashire witches may well be to something like the puppet play described by Thomas Crosfield and Georg Rudolph Weckherlin (Wiggins #2478) rather than Heywood and Brome's play of 1634 (Wiggins #2441).

The notorious forger of Shakespeareana, William Henry Ireland (1775-1835), wrote a play called Henry II which -- along with a "manuscript" of King Lear, pages of Hamlet and various letters and poems -- he claimed as a genuine Shakespearean artefact. It appears he stumbled upon the choice of subject matter by chance, but was serendipitously gratified (his editor and father, Samuel Ireland, declared) by the subsequent revelation of the SR entry for a play of the same name and attribution (Ireland iii). The play's modern editor, Jeffrey Kahan, notes that "Ireland's plot is almost certainly taken from Drayton's two poems on the subject: "Rosamond to Henry the Second" and "Henry to Rosamund", published in Drayton's Poems (1619). The forger does not seem to have heavily consulted Samuel Daniel's "The Complaint of Rosamund" (1592), which shifts much of Rosamund's moral responsibility for the affair from Rosamund to the King" (Kahan 6).

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated 25 Feb 2015.