Fragment of a play in the Journal of Benjamin Greene

Historical Records

Benjamin Greene's journal

The following dramatic fragment appears in the journal of Benjamin Greene:

(British Library, India Office Marine Department Records, IOR/L/MAR/A/XII; reproduced with permission)

| Corus | ||

| Astorildo emperor coelicia | Carrabunculo R fletruria | |

| Cleobulo & Druball his sonnes | Brufard his bastard sonne | |

| Corderia his wife | Merinda his wife | |

| liuia her daughter | Dionisia his faire daughter | |

| Lord Pridamor | Catropus Brufards frend | |

| lo: Parracie | flox (?) the hostler | |

| Jack Pretty Cleobuloes man | Nibs the coachman | |

| Tuckit Druballs man | Racrox & Rabix [illegible] | |

| Attendants | ||

| Cristobell | ||

| Vna | ||

| Plebia | ||

| Curia &c. |

- Enter at one dore---Corus

& Racrox at thother

- Ra. Welmet frend what newes if thou wilt goe to the rose we will a cupe of merrigoe downe.

- Co. I pray keepe of you are a great disturber of the common.

The fragment was first published by William Foster (in "Forged Shakespeariana", 42) as an afterthought, following discussion of the supposed performances of Hamlet on board The Dragon in 1607. It comes from a journal recording a separate voyage (see Theatrical Provenance), but was offered by Foster as evidence of the theatrical interests of East India Company crew members more generally.

Theatrical Provenance

Benjamin Greene was a factor (one of the third class of the East India Company's servants) on the Darling, one of three ships (the others being the Peppercorn and Trades Increase) in the EIC's sixth voyage (to Surat in western India, 1610-13), under Sir Henry Middleton's leadership. Greene's journal records events from 15 November 1610 to 22 December 1612, at which point Middleton's ships had reached Bantam on Java. (Greene would die at Bantam, although he was apparently still alive in February 1613 [Jourdain 236, 243].) Greene does not refer to any performances, but the transcription above occurs on a sheet at the end of his diary (Foster 42).

Probable Genre(s)

Unknown.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

While no direct narrative source is obvious, the fragment's characters' names are evocative of the sixteenth-century prose romance tradition. Astorildo is a character in the third installment of the sprawling Spanish romance Espejo de príncipes y caballeros (written by Marcos Martínez, published 1587), which appeared in English translations around the turn of the century, as the Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth books of The Mirror of Knighthood series, published from 1598 to 1601. (Astorildo only appears in the last three books; a "Cleobulo" is mentioned once in the Ninth [sig. Qq2v] although the name Cleobulus was more readily familiar as one of the Seven Sages of Greece.) Besides its use in the Espejo, the name Astorildo also appears in Belianís de Grecia (1545). That both of these Spanish texts are found in Don Quixote's library is indicative of their genre. The names Corus, Drubal, and Pridamor all appear in Emanuel Ford's popular English romance Parismus, the Renoumed Prince of Bohemia (1598) and its sequel Parismenos (1599).

For more details on the characters' roles in the prose romances and conjectures about the place names in the fragment, see For What It's Worth below. For a selective list of dramatic allusions to the Mirror of Knighthood series, see the LPD entry for "Torrismount".

References to the Play

None other than Greene's fragment.

Critical Commentary

Sydney Race suggested that the fragment was a Collier forgery, but as Foster points out, "Surely it would have been quite natural for some unknown person to have alleviated the tedium of a voyage by trying his hand at dramatic composition; and in this connexion I may recall that Dr. Boas found in the British Museum a whole play [i.e. William Mountfort's The Launching of the Mary], written by one of the Company's servants on his homeward way" ("Reply", 414).

Frederick S. Boas, who assumed that the play was titled "Corus," cautioned that the fragment "may have been added to the journal after it had left Greene's hands" (88n).

Wiggins notes that the dramatic fragment is written in a different hand and ink than the final journal entry, which is dated 22 December 1612 (#1705). He also notes that the MS was "probably in the possession of Richard Hakluyt from 1613 to 1616, and thereafter in the keeping of the East India Company."

For What It's Worth

Character and Place Names

As discussed in Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues above, some of the fragment's characters' names are found in sixteenth-century prose romances. In none of these cases, however, are the characters involved in the same episodes.

- In the Espejo, Astorildo is initially introduced as a brother of one of the main characters, Rosamundi, princess of Calidonia. He plays a more sustained role later, when we encounter him in his travels as a knight errant, "performing many braue deeds vnder the name of the knight of the Griffon" (Eighth, sig. P4r ). He meets Rosicler and the two quarrel about the proper motive for valour—love or reward. They enter a city where knights have gathered for the challenge of the "Louers Pauillion," a tent in which the beautiful Belisa sits under the vengeful spell of the necromancer Nycostratos, protected by two similarly enchanted knights (who had also loved her) "vntill there were a knight so amorous and valiant, but as vnhappie as eyther, that by vanquishing might restore them their lost libertie" (sig. Q3r). Astorildo, who since entering the city has fallen in love for the first time with the lady Eufronisa, attempts the challenge, and, notwithstanding his unprecedented progress, ultimately fails (sig. Q3v). Rosicler is victorious. Later, in the Ninth installment, Astorildo plays a part in a battle. (See also Campos García Rojas 55-56, 76.)

- In Belianís de Grecia, Astorildo is the brother of Andrómaca (Andromache), becoming king in the aftermath of the Trojan war, and a sage of magical arts. He enchants Policena (Polixena), a daughter of Priam and Hecuba, when she refuses to reciprocate the love of his son; the heroes Lucidaner and Clarineo, brothers of Belianís, rescue her. Later, Astorildo defends Troy against the attacks of the Greeks, but is killed by Don Belanio, Belianís's father and the emperor of the Greeks (Nasif 21-22, 46-47, 55; Gallego García 12, 28, 69).

- In Parismus (chapters 20 and 21), a kind hermit named Antiochus tells Parismus that he was once the ruler of the island before he was usurped by Druball, his sometime favorite, now "the most vildest traytor liuing on the earth" (sig. T3r). Joining the witch Bellona, Druball has assumed sovereignty and imprisoned Antiochus' family in the impenetrable castle from which Druball and Bellona wickedly rule. Parismus and his friend Polipus volunteer to avenge the injustice. They manage to penetrate into the castle, but Bellona casts a sleeping spell upon them and imprisons them. During their captivity, the witch becomes infatuated with the knights; Polipus discerns her lust and, when alone with her in a garden, he breaks her neck and steals her keys. Parismus and Polipus both freed, the two knights then attack Druball's servants, imprison the tyrant, and free Antiochus' family. Surveying the castle, Druball's cruelty becomes apparent: "they beheld in sundrie places, the dead carkasses of Thousands of men, women, and children, consumed to Ashes, for assoone as the tyrants had satisfied their appetites in sundry abhominable sorts with them, they burnt their bodies" (sig. X3r). The castle itself vanishes in a tempest of winds and smoke; Druball, understanding this to be a sign of Bellona's death, kills himself and is "cast as a pray to the beastes of the fielde for that he was not woorthie of buriall" (sig. X3v). Antiochus is reunited with his family and restored to the throne.

- In Parismenos (chapter 4), Corus is introduced when the eponymous hero finds himself shipwrecked upon Thrace. A "suspitious and enuious knight," Corus advises the Thracian duke not to trust Parismenos and challenges him to a duel (sig. D1r). Eventually Corus is killed in the fight, only to be scorned by the duke as "the most proude and discourteous knight that euer liued in Thrace (sig. D2v).

- In Parismenos (chapters 28-31), Duke Pridamor is "a valiant and resolute Noble man" to whom Maximus, the King of Natolia, gives the command of the Natolian army in a battle against the story's heroes (sig. Cc1v).

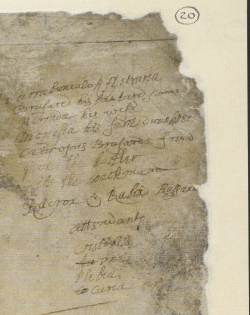

Detail of the dramatic fragment. Courtesy of the British Library |

If, in the fragment, Astorildo is identified as "emperor coelicia," perhaps this indicates Celicia (or Cilicia), north of Cyprus in Asia Minor (map). (This would make his role interestingly similar to the Trojan king Astorildo of Belianís de Grecia.) It might also be logical to understand the two characters names at the top of each column representing different rulers. While Foster's transcription "Carrabunculo R[ex] fletruria" is somewhat perplexing (see detail in the image to the right), the final word might perhaps be explained as a transcription error for Hetruria (or Etruria—that is, Tuscany) if the manuscript used an unfamiliar majuscule H graph that could be misread as fl. Cilicia and Etruria, then, would represent two, perhaps antagonistic, mediterranean kingdoms between which the play's narrative could unfold. (It is also possible that the fragment represents a transcription and that the scribe mistook his source: see "Scribal Corrections" below.)

The Rose was a fairly common tavern sign in London. In 1636, John Taylor, the Water Poet, counted ten around London and Westminster (sig. D2r). Some of these Roses are mentioned in contemporary drama, such as Haughton's Englishmen for My Money, Munday et al.'s 1 Sir John Oldcastle, The London Prodigal, and Dekker and Middleton's The Roaring Girl (Sugden 440; Hoy 3:53). While a local tavern allusion would be appropriate in city comedies such as these, it seems somewhat in tension with the apparent Mediterranean setting suggested by the fragment's characters' names. (OED defines "merry-go-down" as "Strong ale," and cites usages in Nashe's Lenten Stuff and Heywood's 2 If You Know Not Me.)

Scribal Corrections

Foster's published transcription does not indicate corrections made by the scribe. In the character list, the scribe wrote "Au" before correcting to "Vna". The final name was begun "Ca" before correcting to "Curia." In the first line of dialogue, the scribe seems to have written "Welcome frend," which was then corrected to "Wel met frend."

Benjamin Greene

Greene, the "cheefe Marchaunt in the Little Darling," composed his journal in accordance with the Company's commission that "contynuall & true Iournalls be kept of euery dayes Nauigacion duringe the whole voyadge" by the principal members of each ship (Birdwood 329, 331). Greene spoke Spanish, French, and Italian (CSP Colonial 2:197).

According to John Jourdain, Greene fell ill at Pasaman in October 1612 and died at Bantam (235-36). His will, which he wrote in his sickness, is dated 5 February 1613 (National Archives, PROB 11/137, f. 213v). The will also provides some clues about Greene's background. Besides legacies granted to Sir Henry Middleton and various crew members of the Trade's Increase, Greene also left bequests to his father Edward, his mother Mary, and "the poore of Henbury and Bartley in Glocestershire neere Bristoll" (f. 213r). If this is an accurate indication of his origins, we can then be fairly confident that he is the same "Beniamyn Greene," son of Edward, who was baptized on 29 January 1586 at Saint Augustine the Less, Bristol (Bristol Record Office, P/ST.Aug/R/1/(a), f. 10v; qtd. Sabin 9; Ancestry.com). Greene would thus have been twenty-seven when he died.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated by Misha Teramura, 16 May 2017.