Death of the Lord of Kyme, The

Historical Records

Documents relating to Lincoln v. Dymoke, Bayard, et al.

The performance of "The Death of the Lord of Kyme" in August 1601 was the focal point of a bill of complaint sent by Henry Clinton, 2nd Earl of Lincoln, in November of the same year. Lincoln's bill of complaint, the documents prepared for subsequent legal proceedings in Star Chamber (largely comprised of the testimony of the defendants: Lincoln's nephews, Sir Edward and Tailboys Dymoke; and actors in the play Roger Bayard, Marmaduke Dickinson, John Craddock junior, and John Craddock senior), and various sentencing notes recording the verdict contain the only extant evidence of the play. The documents are:

- The National Archives [NA], STAC 5/L1/29, containing the examination of Marmaduke Dickinson; examinations of Tailboys Dymoke, John Craddock junior, and John Craddock senior; interrogatories for Sir Edward Dymoke; interrogatories for Roger Bayard; depositions of Sir Edward Dymoke and Roger Bayard; bill of complaint of Henry Clinton, earl of Lincoln; interrogatories for Marmaduke Dickinson; and interrogatories for Tailboys Dymoke, John Craddock senior, and John Craddock junior.

- NA, STAC 5/L34/37, containing the examinations of William Scotchye and Robert Hychcock, witnesses on the plaintiff's behalf; and interrogatories for William Scotchye and Robert Hychcock.

- Huntington Library, EL 2723, recording fines in various suits involving Lincoln and Sir Edward Dymoke.

- Huntington Library, EL 2733 (1), containing sentences in Lincoln v. Dymoke, Bayard, et al.

- Huntington Library, EL 2733 (2), containing sentencing notes in Lincoln v. Dymoke, Bayard, et al.

- Alnwick Castle, MS 9, containing sentencing notes in Lincoln v. Dymoke, Bayard, et al. (HMC, Third Report 57; cited Wiggins 311).

Many of these documents are thoroughly transcribed and described in REED: Lincolnshire (1:269-304, 2:510–12). (In the quotations below, deletions recorded in the REED transcriptions are silently omitted, as are notations indicating interlineations.)

Summary

The performance took place on Sunday 30 August 1601 on a maypole green in South Kyme, Lincolnshire. The nature of the play as a whole remains somewhat mysterious, since the evidence that survives focuses exclusively on the potentially scurrilous or blasphemous episodes of the performance. One record of the final sentencing for the case in 1610 summarizes the alleged offenses as follows:

- a very infamous and libellous Stage plaie, acted on a Sabboath daie vppon a greene before Sir Edwarde dymockes house, in vewe of 300 or 400 persones purposely drawen thither, wherein they personated the said Earle in Apparell, speeche, gesture and name. with much disgrace and infamy: And so grossly That the Standers by. Cryed Shame vppon yt: And after the plaie ended one of them apparelled like a preacher with a booke. went vpp into a pulpitt fastened to the Maypole and vttered prophane and scurrilous matter in manner of a Sermon, Concludinge with a most Blasphemous and gracelesse praier: and therevppon songe a diridge and fyxed a slaunderous Ryme concerninge the Earle on the Mayepole and the Earles Coate of Armes over yt:/ (REED: Lincolnshire, 302)

Unsurprisingly, the testimonies of the various parties prepared as part of the Star Chamber proceedings provide contradictory and discrepant accounts of these episodes and their significance. What follows is a brief overview of some of the major differences.

Lord Pleasure-Her and the Devil. According to Lincoln's original bill of complaint (23 November 1601), the performance of "The Death of the Lord of Kyme" was the product of a collaboration between Sir Edward Dymoke and his brother Tailboys to slander their uncle, the earl of Lincoln, in front of a large assembly of local residents:

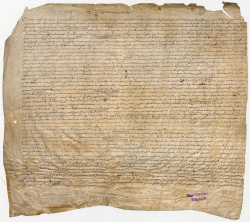

The National Archives STAC 5/L1/29, sheet [21] (Lincoln's bill of complaint), reproduced by permission (click image to view larger version). after sondry plottes and Conferencye had betwene the said Sir Edward Dymocke and him the said Talboys Dymocke howe to scandalize deprave and disgrace your said Subiecte [i.e. Lincoln] the said Talboys Dymocke with the privity procurement and allowance of the said Sir Edward Dymocke in or about the Moneth of August in the xliijth yeare of your Highnes Raigne did frame and Contryve one Infamous Lybell or Stage play which the said Sir Edward Dymocke and Talboys Dymocke tearmed and named the Death of the Lorde of Kyme and to the end that the whole hundred and wapentage adioyning should resorte therevnto and be behoulders thereof: […] and in the afternoone of the said Day ["the last Day of August"] the said Talboys Dymocke Roger Bayard Iohn Cradocke the elder and Iohn Cradocke the younger vppon a Grene neere adioyning to the howse of the said Sir Edward Dymocke at kyme aforesaid hard by A Maypole standing vppon the said greene did then and there present and acte an enterlude or play by the then procurement and privity of the said Sir Edward Dymocke dyveres persons of the Neighbour Townes therevnto adioyning and of the howsehould servants of the said Sir Edward being then [&] there assembled to heare & see the same In which play the said Talboys Dymocke being the then principall actour therein did first then & there Counterfeite and tooke vppon him to represent the person of your said Subiecte and his speaches and gesture and then & there in the said play tearmed & named your said Subiect the Earle of lincolne his good vncle in scornefull manner and as an actor then tooke vppon him to represent the person of your said Subiect and in such sorte representing the person of your said Subiecte in the said play was there fetcht away by the said Roger Bayard who acted and represented then & there in the said playe the person and place of the divell… (ll. 11-23; REED: Lincolnshire, 270–71)

Tailboys Dymoke, in his testimony, denied that his brother had a hand in the composition of the play, and that it was "termed the death of the Lord of kyme because the same day should make an ende of the Sommer Lord game in South kyme for that yeare" (277). (John Craddock junior, who played the part of the Summer Lord of Kyme, recalled being "poisoned & so carried forth" [282].) Dymoke also denied that his own performance was meant to counterfeit Lincoln himself but he rather "did represent & take vpon him the title & terme of Lord Pleasure her & did Calle the Lord of North kyme (being another Sommer Lord that yeare) my vncle Prince But the same was not done in scornefull manner" (278).

The Fool/Vice. Lincoln further complained that Roger Bayard, in addition to playing the part of the devil, also played "the parte of the ffoole and the parte of the vyce," in which role he read out his last will and testament, bequeathing his vice's wooden dagger to Lincoln by name and his fool's cockscomb and bauble to all those who would not go with Sir Edward Dymoke to Horncastle (where, in July, Dymoke had led a "Ryotous entrye into the p[a]rsonage howse" owned by Lincoln) (271; cf. 291-92). Bayard himself, however, claimed that the words he spoke here were "My wodden dagger that same Lord shall haue, that called my Lord of Kyme a pybalde knaue" (295) and denied that he heard Tailboys Dymoke explicitly declare to the audience assembled that this referred to Lincoln. (Apparently, Craddock junior—who played the part of the Lord of Kyme—had been dressed in a piebald coat as the Summer Lord of Kyme during an altercation at Coningsby at which Lincoln had called him a piebald knave [282, 286, 288-89; cf. O'Conor 112-14, 116].)

The Minister. Lincoln's bill of complaint also mentions a minister—played by John Craddock senior—who delivered "a prophane and irreligious prayer" and reading "a Text out of the booke of Mabbe" (272). Craddock himself claimed that this was not originally part of the play but rather an impromptu presentation of older material following the play's conclusion: "after the endinge of the saied Play the aforesaied Talboys Dymocke came vnto this defendantes [i.e. Craddock's] house & verie much vrged him to com vnto the saied Greene & there to deliver an old idle speache which was made about 2. or 3. yeres before by the saied Talbois Dymocke" (284). Craddock also denied that his black gown costume was meant to denote a minister's attire, and claimed that he "did vtter &c reade owt of the saied booke wordes to this effecte viz. de profundis pro defunctis lett vs pray for our deere Lord that died this present day Now blessed be his body & his bones I hope his legges are hotter then gravestones And to that hope letts all conclude it then, both Men & Woemen pray & say amen" (284). According to the playwright, however, the character was indeed meant to represent a "Minister or Prieste," who

- did then & there vtter these wordes & speaches viz. the marcie of Musterd seed & the blessinge of Bullbeefe & the peace of Pottelucke be with you all Amen, of which speches he this defendant was the Inventer & maker And at the same tyme the saied person did reade a text which he saied was taken out of the Hytroclites in these wordes viz Cesar dando, sublevando, ignoscendo gloriam adeptus est & did englishe it this viz. Bayardes leape on Ancaster heathe the Bownder stone in Bollingbrookes fenne I say the more knaves the honester Men And the saied person then devided his texte into three partes viz. the first a colladacion of the auncient plaine of Ancaster heathe the second an auncient storie of Mabb as an appendix & the third concludinge knaves honest menn by an auncient story of the ffriar & the boye And also at the same time the saied person told a Tale of Bayardes leape which he saied was taken owt of the booke of Mabb & then willed the people to goe to one Mr Gedney of Ancaster & he could tell it better. (279–80)

William Scotchye, a witness on the plaintiff's behalf, deposed that there was also "A pott of Ale or beare hanginge by him [i.e. the minister] in steade of an hower glase wherof the said Cradoke Did Drinke at the Concluding of Any poynte or parte of his speech" (289).

The Dirge. Lincoln also described a dirge song that named "most of the knowen lewde & licencious woemen in the Citties of london & lincoln and Towne of Boston concluding in their songes after every of their Names. Ora pro nobis" (271). The interrogatories prepared for the actors also asked whether "some women of Credit and good behaviour" were also named "amongste women suspected" (275), but this was roundly denied.

Although Sir Edward Dymoke was not himself in the audience, Lincoln claimed that he nevertheless controlled the performance, "sen[ding] from tyme to tyme by his servantes and others directions to the said actoures what they should doe" (272). Marmaduke Dickinson confirmed the supposition of an interrogatory that "some Cushions & stoles were sett at the same place which the saied Talboys dymocke told this defendant was for Sir Edward dymock & his Lady to sitt & see the Play" and also that the proximity of the playing place and Sir Edward's residence meant that "if anie were in the topp of the towre or vpper parte of the house of the saied Edward dymocke they might from theare see the saied play plaied" (300). Sir Edward claimed that he only knew about the play after it had been acted, and a witness reported that he immediately rebuked his brother (O'Conor 114, 124).

Theatrical Provenance

Performed at South Kyme, Lincolnshire, on Sunday 30 August 1601 by Tailboys Dymoke, George Bayard, John Craddock senior, John Craddock junior, and Marmaduke Dickinson before an audience of locals.

Probable Genre(s)

Topical Satire (Harbage).

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

Tailboys Dymoke claimed that his play was called "The Death of the Lord of Kyme "because the same day should make an ende of the Sommer Lord game in South kyme for that yeare" (277). Summer games, an annual highlight of English festive culture, often included the election of a mock lord; if Dymoke's play represented a dramatic staging of the death of the traditional Summer Lord, it bears comparison with Thomas Nashe's Summer's Last Will and Testament (O'Conor 118). (Barber notes that the ceremonial Christmas Lord at St. John's Oxford also "died" at the end of the festivities of 1607-8 [50].)

While much of the play seems to be traditional, some of the elements of the minister's mock sermon can be associated with popular entertainment and local allusion. The story of Bayard's Leap appears to have been an enduring part of Lincolnshire mythology. In 1724, William Stukeley writes of "a place, of no mean note among the country people, call'd Byard's leap, where the Newark road crosses the Roman: here is a cross of stone, and by it four little holes made in the ground, they tell silly storys of a witch and a horse making a prodigious leap, and that his feet rested in these holes, which I rather think the boundarys of four parishes" (Stukeley sig. Y1r; qtd. O'Conor 121).

The story of the Friar and the Boy was likely based on the ballad pamphlet A Merry Jest of the Friar and the Boy, which was popular throughout the sixteenth century (O'Conor 121). In the ballad, a little boy named Jack has a cruel stepmother who gives him only a meager diet and attempts to convince his father to send the boy for an apprenticeship. The father proposes instead that they have the boy tend the family's sheep. The next day Jack is sent to the field, where he is happy enough, until he discovers the bad food given to him as a midday meal, from which he forbears. An old man approaches the boy and asks for something to eat. Jack readily shares what food he has, for which the old man is so grateful that he grants the boy three things. The first is a bow and arrow that never miss their mark; the second is a pipe that makes all hearers laugh and dances. Jack attempts to decline a third wish, but eventually asks that whenever his stepmother glares at him, she might let out a resounding fart: the wish is granted. At the end of the day, Jack ushers home the flock with the sound of his pipe, and, hungry, asks his father for something to eat. The moment his stepmother turns to stare at Jack, she lets out a resonant fart, to the amusement of all; she glares again and "another blast she let go / she was almost rent," much to her embarrassment (Friar, sig. A3v). That night, a friar (named Topias) stays at their house. Hearing the stepmother's complaints about the child, the friar promises to beat him the next day. In the field, the friar approaches Jack, threatening punishment unless the boy can explain himself. Jack distracts the Friar by shooting a fat bird sitting on a briar with his new bow and arrow. When the friar goes to collect it, Jack plays his pipe, and the friar is unable to forbear dancing, even as his skin is pricked and his clothes ripped on the thorns. Returning to the house bloodied and bandaged, the friar tells the stepmother that Jack is possessed by the devil. When Jack returns home, his father insists upon hearing the pipe, at which the terrified friar demands to be bound to a post. As soon as Jack plays, the room erupts: the father dances; the mother, glaring at Jack, breaks wind; the friar knocks his head against the post. The merriment continues into the streets, as neighbours join in the dance. Enraged, the friar summons Jack to appear before an official on Friday. On the appointed day, the friar and the stepmother accuse Jack of being a necromancer and a witch. Again Jack is called upon to prove the power of his pipe, and again the assembled company dances with delight. Jack stops only on the condition that "they doo me no vilany," to which all agree (sig. B4v).

The "Mr Gedney of Ancaster," to whom the minister sends the audience, may have been a real person: one William Gedney of Ancaster appears on a tax return of 1600 (O'Conor 121, citing NA, E 179/139/631).

References to the Play

None known. (Information welcome.)

Critical Commentary

O'Conor offers the most comprehensive summary of the testimony as well as the events surrounding the performance (108-26). On the play's genre, he notes:

- it is clear that Talboys Dymoke and his fellow players set up as a defence against the charge of slander that they were behaving in an accustomed manner, which is evidence that, in South Kyme at least, a play must have been a regular part of the May games festival. This presumably lasted through the summer, and was apparently brought to an end by a performance like Thomas Nash's Summer's Last Will and Testament, which is symbolic of the passing of the season. The play by Nash may have been written for a similar occasion at Croydon. (118)

O'Conor also proposes sources for the various parts of the Minister's sermon (see Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues above), and even suggests that the combination of "Mab" and "mustard seed" might indicate the influence of Shakespeare's fairies (119).

Barber, who devotes several pages of Shakespeare's Festive Comedy to an account of the performance, draws comparisons to Old Comedy, with its transformation of "festive abuse […] into ad hominem slander" (39). "It was composed for performance with the license of a festival; it used traditional roles and stock scenes instead of a fully developed narrative plot; the zest of it came from abuse directed at an actual spoil-sport alazon" (40). Barber also notes the traditional elements of the play, such as the conventional carrying-off of a bad character by the Devil and the burlesque dirge incorporating real names (49).

Wiggins notes that John Craddock senior's claim that the mock sermon was an afterthought is undermined by the apparent relevance of the prayer to the action of the play (310).

Egan provides an overview of the evidence of the performance, comparing it to the variety of forms that provincial libels could take (159–61).

Mansky shows how the play demonstrates the "characteristic hybridity of libelous performance," incorporating festive misrule, features of the morality play (especially in its parallels with Mankind), and the multimedia publication of libel in both performance and writing (65–68). As Mansky notes, the performance was not just an occasion for the players to voice their specific grievances against the Earl of Lincoln but it served as an opportunity for the wider community to express their animus towards a deeply unpopular figure: "If we include the merry (or offended) spectators and the prospective marchers on Horncastle, then virtually the whole community had parts to play" (69).

For What It's Worth

The Literary Career of Tailboys Dymoke

While no published works were attributed to Tailboys Dymoke during his lifetime, later scholars have argued for his authorship of two volumes.

Caltha poetarum: Or The Bumble Bee was printed in 1599 with the attribution: "Composed by T. Cutvvode Esquyre." The poem, which takes place in a Lincolnshire garden, is an allegory of Elizabethan court politics in rhyme royal, including pornographic description of erotic acts told through the imagery of bees and flowers (Betts 173–75). Leslie Hotson argued that the name "Cutwood" was an Anglicized pseudonym for Tailboys (taille + bois) (51; Donno xxiv), and that the poem in part allegorized the fraught relationship between the earl of Lincoln and the Dymokes. As Hotson observes (50), the poem criticizes the earl through its description of the anagrammatized city name "Nycol" for "Lincoln": "Thy Earldome (Nycol) then did bear great sway, / But Earldoms, Earles, & Counties now decay" (B1v). Caltha poetarum was one of the publications recalled under the Bishops' Ban of June 1599, along with works including Marlowe's Elegies, Marston's The Scourge of Villanie, and Middleton's Microcynicon, although for unknown reasons it was one of two works not burned at Stationers' Hall (Arber 3:677–78).

Tailboys Dymoke has also been proposed as the author of English translation of Battista Guarini's Il pastor fido, published in 1602. The play was prefaced by "A Sonnet of the Translator, dedicated to that honourable Knight, his kinsman, Syr Edward Dymock" and the dedicatory epistle by the publisher, Simon Waterson, informs us of the recent death of the translator: "by reason of the nearenesse of kinne to the deceased Translator [...] I knew none fitter to Patronize the same then your worthinesse" (A2r). While various candidates have been proposed, Elizabeth Story Donno argued that Tailboys Dymoke is the most likely (xxi–xxiv), an attribution accepted by Wiggins (#1298).

Another work explicitly attributed to Tailboys Dymoke does not survive today. As Hotson discovered, in an earlier Star Chamber trial in 1590, the earl of Lincoln accused Dymoke of authoring a libel that was "published in most foul, slanderous, riming and railing sort, as it were by way poetry" (53). (Hotson does not provide references for the Star Chamber records in question but they seem to be STAC 5/L1/7.) According to Tailboys's brother John, the libel was "entitled 'Faunus his Four Poetical Furies'" and was "divided into four parts, videlicet, into an exordium showing the ground of the discourse; the second dilating upon his native soil, the antiquity of his house and the honorable tenure of the same and lastly the miserable ruin of the same; the third discanteth of the marring of his brother Satirus...; and the fourth the metamorphosis" (54). The earl of Lincoln's charges accused Tailboys's poem of slander against his family—"their persons, arms, badges, and cognizances"—while William Hall, one of the defendants, admitted that the poem included material "tending as well to the defaming of a lady in Lincolnshire as also to the dishonor of" the earl himself (53-54).

Lord Pleasure

Lord Pleasure is the name of a character in Robert Wilson's Three Lords and Three Ladies of London (1590).

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Misha Teramura, University of Toronto; updated 12 March 2024.