Charlemagne

Historical Records

Alleyn's list of theatrical costumes

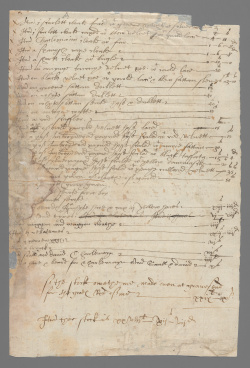

A single folio leaf, undated but possibly c.1589-91, acquired by the Houghton Library in the early 1970s (as part of a larger MS collection) includes a costed inventory of theatrical costumes, apparently compiled by John Alleyn and at one time in the possession of Edward Alleyn. It was first found in a copy of John Payne Collier's The History of English Dramatic Poetry (1831), which Collier had presented to Joseph Hazlewood the year it was published. Hazlewood had it inserted between pp.88-89 of volume 3. It thereafter passed to Augustus, sixth Lord Vernon, and ultimately to Arthur Freeman before Harvard acquired it (see Evans 254-55).

|

|

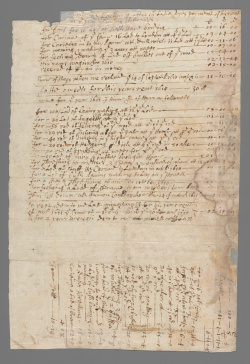

| f MS Thr 276 recto | f MS Thr 276 verso |

f MS Thr 276, Houghton Library, Harvard University; reproduced by permission.

[fol. 1r] includes the following items pertaining explicitly to the lost "Charlemagne" play (it is possible that other items on the list also belonged to "Charlemagne" or were at least shared by that play and the "Saul and David" play also listed):

- X Itm Charlemains cloake wt fur. _____________________________1-6-8d

- ...

- X Itm saull and dauid. Charlemayn __________________________iiijll

- X Itm a hare & beard for Charlemayn And Saull & dauid ___________xs

The £4 paid for "Saul and David" and "Charlemagne" is apparently for the playbooks.

Theatrical Provenance

Unknown; Peele's reference (below) implies general familiarity with the play by 1589, and the association (in that poem) with Tamburlaine and plays about "Mahomet" and "Tom Stukely" at "theatres" with "proud tragedians" implies a London commercial company as the likely auspices, but the play has not been associated with any specific company. Wiggins (#808) suggests the play "may have entered the repertory of a touring company, perhaps one bound for the Continent" (presumably his conjecture rests on the concluding comment, "so the stock oweth me made euen at grauesend" in line 31 -- Gravesend being a possible port (see Evans 266). Evans suggests an association with the Worcester's or Admiral's companies, on the basis of the Alleyn connection (266).

Probable Genre(s)

Tragedy (?) (Wiggins).

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

The French King Charlemagne (reigned AD 768-814), subsequently Holy Roman Emperor, was known to the English via such sources as Tyndale and Foxe. The details of his military exploits are typically prioritised, and are most likely to have been dramatised given the heroic nature of the other allusions in Peele's poem, but a second, intriguing aspect of the Charlemagne story was also available: his infatuation with a concubine and her magic ring.

Conquests

As Tyndale notes, "This Charles was a great conquerour that is to say a great tyraunt, & ouercame many natio[n]s with the sword, and as the Turke compelleth vs vnto his fayth, so he co[m]pelled the[m] with violence vnto the faith of Christ say the stories" (350). Following his mother's advice, he married the daughter of Desiderius, king of Lombardy, but left her after a year. He ruled with his brother Caroloman until Caroloman's death; thereafter (as Foxe reports) "his wife called Bertha with her two Children came to [Pope] Adrian, to haue them confirmed in their fathers kingdome", but the Pope "gaue the mother with her two children, & Desiderius the Lombard king with hys whole kingdome, hys wife and Children, into the hands of the said Carolus [i.e. Charlemagne], who led them with him captiue into Fraunce, and there kept them in seruitude during their lyfe" (Foxe, Book 2, 131). Pope Adrian proceeds to make Charlemagne the Holy Roman Emperor.

Concubines

Tyndale reports that Charlemagne was "a filthy whoremonger" who kept four concubines and even lay with two of his own daughters, and that "in his old age a whore had so bewitched him with a ryng and a pearle in it" that even after she died, he "he could not departe from the dead corps, but caused it to be enbalmed & to be caryed with him whether soeuer he went, so that al the world wondered at him":

- at the last his Lordes accombred with carying her from place to place and ashamed that so old a man, so great an Emperour and such a most Christen kyng, on whom & whose dedes euery mans eyes were set, should dote on a dead whore, toke counsell what should be ye cause. And it was co[n]cluded that it must nedes be by enchauntement.

One of the lords confiscated the enchanted ring from the corpse, but Charlemagne in turn became inseparable from the ring-bearing lord, who was ultimately forced to cast the ring into a well:

- And after that the ryng was in the well the Emperour coulde neuer depart from the towne, but in the sayd place where the ring was cast, though it were a foule marresse, yet he built a goodly monastery in the worship of our Lady, and thether brought reliques, from whence he coulde gette them, and pardo[n]s to sanctifie ye place, & to make it more haunted. And there he lyeth, & is a Saint, as right is. (Tyndale 350)

References to the Play

In his poem, A farewell Entituled to the famous and fortunate generalls of our English forces: Sir Iohn Norris & Syr Frauncis Drake Knights, and all theyr braue and resolute followers (1589), George Peele encourages the imminently departing soldiers to bid farewell to fictional adventures and prepare for actual battle:

- Bid all the louelie brittish Dames adiewe,

- That vnder many a Standarde well aduaunc'd,

- Haue bid the sweete allarmes and braues of loue.

- Bid Theaters and proude Tragædians,

- Bid Mahomets Poo, and mightie Tamburlaine,

- King Charlemaine, Tom Stukeley and the rest

- Adiewe: to Armes, to Armes, to glorious Armes,

- With noble Norris, and victorious Drake,

- Vnder the Sanguine Crosse, braue Englands badge...

- sig.A3 (EEBO-TCP, Open Access)

Critical Commentary

Harbage does not list this play, but the date range of 1584-c.1605 that he provides for the MS play Charlemagne, or the Distracted Emperor (poss. Chapman) implies that he may have considered the inventory list or Peele's reference in 1589 to refer to that surviving play.

Wiggins (#808) notes that Peele's "poem cannot refer to the extant MS play about him [i.e. Charlemagne], which dates from the 1610s or early 1620s". Consequently, the Alleyn inventory and the Peele reference appear to refer to a lost play.

Evans draws a long bow in suggesting that the other named play in the Alleyn inventory, "Saul and David", may be a prequel of sorts to Peele's David and Bathsheba; this, in conjunction with the possibility that Peele's poem may refer to Peele's own Battle of Alcazar when it mentions "Mahomets poo", leads Evans to conjecture that Peele himself might be the author of "Charlemagne:' "given the tentative connection of Peele with 'saull and dauid' and his interest in celebrating 'King Charlemaine,' an otherwise unknown stage hero, we may perhaps hazard even further and suggest that Peele may be considered as the possible author of 'Charlemayn.'" (268). Evans' ascription has not gained acceptance.

For What It's Worth

Other items in Alleyn's list that may or may not be associated with the "Charlemagne" play include various cloaks and doublets described only by their colour and material; white and yellow beards; periwigs; a "waggon and waggon cloathe", a "trunck"; and more specifically, "a hermyttes gray gown", a "pasytes [parasite's] sewte for a boy", and "a clownes sewte".

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated 20 April 2017.