Angel King

Historical Records

Dramatic Records of of Sir Henry Herbert

J. O. Halliwell-Phillips transcribed a number of Sir Henry Herbert's licensing records and compiled them in various scrapbooks now held at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Amongst them is the following transcription of plays from 1624, which includes:

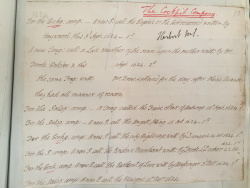

For the Palsg: comp: -- A new P. call: The Angell King 15 Oct. 1624 - 1 li.

- (Folger Shakespeare Library, MS W.b.156 ("Fortune"), p149. Reproduced by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library)

In 1996, N. W. Bawcutt published new records deriving from hitherto overlooked transcriptions and cuttings from the Ord manuscript, made by its previous owner (i.e. previous to Halliwell-Phillipps) the nineteenth-century scholar Jacob Henry Burn (Beinecke Library, Osborn d1):

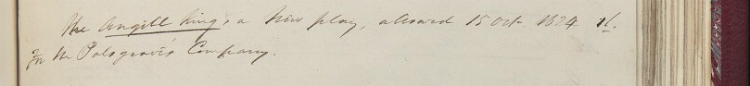

The Angill King, a New Play, allowed 15 Oct 1624 1l.

For the Palsgraves Company.

- (Jacob Henry Burn, "Collection towards forming a history of the now obsolete office of the Master of the Revells", [1874]. James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Reproduced with permission).

Theatrical Provenance

Palsgrave's Company at the Fortune

Probable Genre(s)

Unknown (Harbage); doppelganger comedy (Fleay and Steggle)

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

"The story of Robert, King of Sicily, I suppose" (F. G. Fleay, BCED, 2.327).

Fleay is alluding to a tale which survives in many versions, typified by the very popular medieval English poem Robert of Cisyle. In this tale, a proud king goes to church and during the service unwisely declares that he is so powerful that nothing can remove him from his throne. He promptly falls asleep, and awakes to find the church deserted, with his own appearance transformed into that of a beggar. Robert rushes out of the church and is treated, by all of his courtiers, as a madman. No-one will believe his protestations that he is the true ruler of everyone he meets, since, as becomes apparent, a stranger has taken on Robert’s own form and supplanted him as king without anyone noticing the difference. Robert attempts to gain entrance to his throne room; scuffles with his own porter; and comes face to face with his double, who is in fact an angel in disguise.

Robert is taken from the court in disgrace, still unrecognized. He is forced to wear the garb of a fool, imprisoned, and given an ape for a counsellor, who is dressed in the same clothing as him. Still he refuses to relinquish his claim that he is the real king. After many humiliations, Robert finds that he is indeed tolerated only as a fool at the court of the new king. For three years the stranger rules Sicily with great success. Finally, Robert of Sicily has a religious conversion; realizes that he is indeed a mere fool measured against God; and accepts his new role as a fool. When he tells the impostor this, the impostor reveals that he is really an angel. He at once returns to Heaven, and Robert finds that he is once again recognized by those around him as the King of Sicily.

Later English-language versions of the tale include a prose narrative by Leigh Hunt, published in A Jar of Honey from Mount Hybla (1848); and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem "The Sicilian’s Tale", a narrative poem within the hugely successful collection Tales from a Wayside Inn (1863). "The Sicilian's Tale", in turn, prompted a large number of further versions and the poem was well known at the time that Fleay was writing.

One obvious potential problem with Fleay's argument is that the eponymous character in the medieval poem is not the angel, but the man he usurps. Indeed, the medieval English poem never uses the exact phrase "the angel king".

References to the Play

None known.

Critical Commentary

This is one of a group of at least fifteen new plays licensed by Herbert between July 1623 and November 1624 for the Palsgrave’s Company, formerly the Admiral's Men. In 1621, their theatre, the Fortune, had burnt down, and three years later they were still attempting to recover from the destruction not merely of their venue but also, it is thought, of their stock of playbooks. This concentration of new writing for one company, fifteen plays in little over a year, is unparalleled in Herbert's records. Fourteen of the fifteen are lost, the survivor being Thomas Drew's The Duchess of Suffolk. As far as one can tell, the post-fire licensings represented an attempt to rebuild a working repertory. See Gurr, Shakespeare's Opposites, 47; Bentley, 1.149; Bentley, 5.1327-8.

This particular play attracted almost no attention prior to the Lost Plays Database apart from Fleay's uncharacteristically diffident suggestion as to its possible source in the Robert of Sicily story. Sibley (8) and Bentley (5.1290-1) both quote Fleay's sentence without evaluative comment or addition.

In work arising from the LPD, Steggle argues in support of Fleay's case by adducing other instances where versions of the Robert of Sicily story are entitled "The Angel King". In particular, he cites two separate dramatizations of the Robert of Sicily story, each based on Longfellow's version and recorded in the later nineteenth century, each entitled "The Angel King".

There are, furthermore, numerous early modern continental versions of the Robert of Sicily story, many of which refer to the angel using variants of the relevant phrase. In particular, two seventeenth-century Spanish plays - El Rey Angel, and El Demonio en la Muger, y Rey Angel de Sicilia - actually use the phrase in their titles. Steggle argues that the texts he adduces show

- …firstly, that the story remains current in seventeenth-century Europe, and secondly that the angel is often referred to at this date in variants of the phrase "the Angel King". Additionally, El Rey Angel, and El Demonio en la Muger, y Rey Angel de Sicilia… show that the title The Angel King has not just nineteenth-century but also seventeenth-century warrant as an appropriate one for a dramatization of the story of Robert of Sicily. (142)

If this identification is accepted, then The Angel King becomes "one of the large number of Renaissance plays inheriting and remaking the materials of medieval romance" (143). It also becomes a play about doppelgangers, joining a small group including Twelfth Night and The Comedy of Errors. Steggle also notes the existing suggestion, made by Donna B. Hamilton among others, that the story of Robert of Sicily lurks in the imaginative hinterland of King Lear.

For What It's Worth

See also King Robert of Siciliy, a lost play acted by the students of the Jesuit College at St Omer in 1623.

Robert confronts the Angel. From Longfellow, Robert of Sicily, illus. Jane Willis Grey (London, n.d.).

Works Cited

Longfellow, [Henry Wadsworth]. Robert of Sicily, illus. Jane Willis Grey (London, Raphael Tuck and sons, n.d.).

Page created by David McInnis, University of Melbourne, and Matthew Steggle, Sheffield Hallam University; updated 16 December 2016.