Lord and his Three Sons, A

Historical Records

Henry Peacham's account

In his The Truth of our Times: Revealed out of one Mans Experience, by way of Essay (London, 1638), Henry Peacham (1578-c.1644)---the man responsible for the sketch of Titus Andronicus in the Longleat manuscript---includes the following anecdote in his section “Of Parents and Children”:

- Sometimes among Children the Parents have two hopefull, and the third voyd of all grace: sometimes all good, saving the eldest.

- I remember when I was a School-boy in London, Tarlton acted a third sons part, such a one as I now speake of: His father being a very rich man, and lying upon his death-bed, called his three sonnes about him, who with teares, and on their knees craved his blessing, and to the eldest sonne, said hee, you are mine heire, and my land must descend upon you, aud I pray God blesse you with it: The eldest sonne replyed, Father I trust in God you shall yet live to enjoy it your selfe. To the second sonne, (said he) you are a scholler, and what profession soever you take upon you, out of my land I allow you threescore pounds a yeare towards your maintenance, and three hundred pounds to buy you books, as his brother, he weeping answer'd, I trust father you shall live to enjoy your money your selfe, I desire it not, &c. To the third, which was Tarlton, (who came like a rogue in a foule shirt without a band, and in a blew coat with one sleeve, his stockings out at the heeles, and his head full of straw and feathers) as for you sirrah, quoth he) you know how often I have fetched you out of Newgate and Bridewell, you have beene an ungracious villaine, I have nothing to bequeath to you but the gallowes and a rope: Tarlton weeping and sobbing upon his knees (as his brothers) said, O Father, I doe not desire it, I trust in God you shall live to enjoy it your selfe. (102-05)

Peacham concludes, “There are many such sons of honest and carefull parents in England at this day” (105).

Theatrical Provenance

From Tarlton's performance of the scene-stealing role, this play appears to have been in the Queen's Men's repertory in the 1580s, probably c.1585 at the earliest (Peacham would have been 7 years old at that point).

Probable Genre(s)

Comedy.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

The division of an estate or kingdom was a common enough motif, and the Queen's Men would themselves subsequently stage a similar scenario in The True Chronicle History of King Leir (before 1594). A Stationers’ Register entry for 20 January 1595/6 conceivably suggests a similar “kingdom-division” story, and may have furnished the plot of another lost play, “Crack Me This Nut” (1595, Admiral' men):

Master Ponsonby. Entred for his copie vnder the hands of the Wardens A booke

Intitled The Paragon of pleasaunt histories . . . vjd

Or this Nutt was neuer Cracked Contayninge a Discourse of a

nobl[e] kinge and his Three sonnes /

(S.R.1, 3.57 / Fol.7)

However, Hazlitt suggested some analogy between the subject of the Tarlton play and that of a poem, A Delectable Little History in Meter: Of a Lord and His Three Sons, which appeared in print at the end of the seventeenth century. This poem is a liberal redaction of the Fortunatus legend. As Albert Feuillerat notes, “[t]he history of Fortunatus was published for the first time in Augsburg in 1509” in the German Volksbuch, but there were other analogues, including the story of King Darius’s legacy as told in Thomas Hoccleve’s Jonathas and in the Gesta Romanorum, amongst other places.

In the Delectable Little History poem, the three sons (not two, as in Thomas Dekker’s Old Fortunatus, 1599) receive their father’s land (the eldest son), his magically replenishing purse (the middle son), and their father’s wishing cap (a mantle in this case; given to the youngest son, who is a scholar, and had actually requested books as his inheritance). Inasmuch as the father bequeaths land to one son and has another son with scholarly interests, there is indeed some similarity between the poem and the lost Tarlton play; especially given the context of a death-bed division of a father’s estate between his three sons. But therein ends the similarities. There is no hint, in Peacham’s account, of a magical wishing cap, or a bottomless purse, and thus no strong reason to connect the Tarlton play to the Fortunatus legend specifically. Nor is there any reason to connect the Tarlton piece to the lost “1 p of forteunatus” play which preceded Dekker’s, and was performed as an old play (Henslowe did not mark it “ne”) by the Admiral's men from 3 Feb 1595/6 onwards, but which was probably composed c.1590 or earlier.

Wiggins, Catalogue #780 ("Play with a Deathbed Scene") proposes A Hundred Merry Tales (1527) as the source for the narrative.

References to the Play

Only Peacham's eyewitness account (see Historical Records above).

Critical Commentary

There is no reference to such a play in any of the major criticism: Alfred Harbage does not list it in his Annals of English Drama, E. K. Chambers does not refer to it in his Elizabethan Stage, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography contains no mention of it in the entry for Richard Tarlton, and there is no description of it in the authoritative study of the Queen’s Men by Scott McMillin and Sally-Beth Maclean.

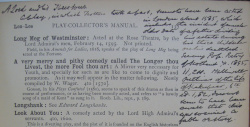

Detail of Hazlitt's marginalia, p137. Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library |

The Folger Shakespeare Library’s holdings include W. Carew Hazlitt’s annotated copy of his own A manual for the collector and amateur of old English plays (1892). The marginalia largely consists of Hazlitt’s private speculations about certain titles, some of which were clearly intended as notes for a revised copy of the Manual, which it seems was never published. It appears that Hazlitt had planned to incorporate the following information in an updated edition of the Manual:

- A Lord and His Three Sons. A play, in which Tarlton took a part, seems to have been acted in London about 1585, which includes the incident of much older date of a father dividing his estate among his three children on his deathbed. See my Pop. Poetry of Scotland, etc. 1895, ii, 211. Halliwell, Outlines of the Life of Shakespear, 6th ed. i,82, does not seem to have been aware that this was so ancient a fable or story.

As Hazlitt notes, James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps does provide a description of the play in his Outlines of the Life of Shakespeare:

- There was another drama that was played in London about the same time, one in which Tarlton’s personation of a dissolute youth was singularly popular and long remembered. In this latter was a death-bed scene, a notice of which may be worth giving as an example of the dramatic incidents that our ancestors relished in the poet’s early days;—A wealthy father, in the last extremity of illness, communicates his testamentary intentions to his three sons. His landed estates are allotted to the eldest, who overcome with emotion, expresses a fervent wish that the invalid may yet survive to enjoy them himself. To the next, who is a scholar, are left a handsome annuity and a very large sum of money for the purchase of books. Affected equally with his brother, he declares that he has no wish for such gifts, and only hopes that the testator may live to enjoy them himself. The third son, represented by Tarlton, was now summoned to the bed-side, and a grotesque figure he must have appeared in a costume which is described by an eye-witness as including a torn and dirty shirt, a one-sleeved coat, stockings out at heels, and a head-dress of feathers and straw. “As for you, sirrah,” quoth the indignant parent, “you know how often I have fetched you out of Newgate and Bridewell;—you have been an ungracious villain;—I have nothing to bequeath to you but the gallows and a rope.” Following the example of the others, Tarlton bursts into a flood of tears, and then, falling on his knees, sobbingly exclaims,—“O, father, I do not desire them;—I trust to Heaven you shall live to enjoy them yourself. (82-83)

The same anecdote appeared at least three years earlier in the 3rd edition of 1883 (p.86). Halliwell-Phillipps does not provide his source, but it appears that the eyewitness he refers to is the writer and illustrator, Henry Peacham (see Historical Records above).

See also Wiggins, Catalogue #780.

For What It's Worth

(Information welcome)

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated 24 April 2011.