Duchess of Fernandina: Difference between revisions

m (Text replacement - "\[\[(i|I)mage:(.+)\|link=https?:\/\/(www\.)?lostplays.org\/images\/[\a-zA-Z0-9]+\/[\a-zA-Z0-9]+\/(.+)\]\]" to "<!--newThumb-->250px<!--/newThumb-->") |

|||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

:The Dutchesse of Fernandina. a Tragedy [brace] | :The Dutchesse of Fernandina. a Tragedy [brace] | ||

:::(Greg, ''BEPD'', 1.68) | :::(Greg, ''BEPD'', 1.68) | ||

<br> | |||

===[[Warburton's List]]=== | ===[[Warburton's List]]=== | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

:The Dutches of Fernandina T. Hen. Glapthorn | :The Dutches of Fernandina T. Hen. Glapthorn | ||

:::(Greg, "Bakings", 252-9) | :::(Greg, "Bakings", 252-9) | ||

<br> | |||

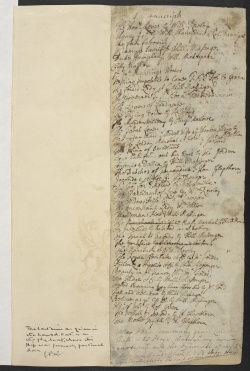

<!--newThumb-->[[Image:Lansdowne_ms_807_f001r.jpg|250px]]<!--/newThumb--> | |||

<br> | |||

:(British Library, Lansdowne MS 807, fo.1<sup>r</sup>. Reproduced by permission of the British Library. Click image to view full page; [[Warburton's List|'''click here for more information on Warburton's list''']]) | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==Theatrical provenance== | ==Theatrical provenance== | ||

Unknown. | Unknown. Glapthorne is known to have been active throughout the 1630s, for a range of different dramatic companies (see below). The date range given above is from Harbage. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==Probable genres== | ==Probable genres== | ||

Tragedy (per Stationers' Register entry). | Tragedy (per Stationers' Register entry). | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

== Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues == | == Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues == | ||

Fernandina, modern Cuba, gained its first Duke in 1559, although there is no evidence that any of the early Dukes resided there. The first Duke of Fernandina was the Spanish grandee, Don García Álvarez de Toledo y Osorio (1514-1577), fourth Marquis of Villafranca del Bierzo. By the time that Glapthorne was writing, Don Garcia had been succeeded, first by his son Pietro, and then by Pietro's son Garcia, third Duke of Fernandina. Thus, if this play is historical, there is a fairly limited selection of family history available to provide Glapthorne's source material. For a more specific suggestion, see "Critical Commentary" below. | Fernandina, modern Cuba, gained its first Duke in 1559, although there is no evidence that any of the early Dukes resided there. The first Duke of Fernandina was the Spanish grandee, Don García Álvarez de Toledo y Osorio (1514-1577), fourth Marquis of Villafranca del Bierzo. By the time that Glapthorne was writing, Don Garcia had been succeeded, first by his son Pietro, and then by Pietro's son Garcia, third Duke of Fernandina. Thus, if this play is historical, there is a fairly limited selection of family history available to provide Glapthorne's source material. For a more specific suggestion, see "Critical Commentary" below. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==References to the Play== | ==References to the Play== | ||

None known. | None known. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

== Critical Commentary == | == Critical Commentary == | ||

"Moseley's entire list of 29 June 1660 is a curious one", comments Bentley (4.493-4), observing that most of the plays on it have disappeared. | "Moseley's entire list of 29 June 1660 is a curious one", comments Bentley (4.493-4), observing that most of the plays on it have disappeared. | ||

W. W. Greg argued that Warburton may not have possessed the manuscripts that he claims to have lost. His list, argues Greg, derived from Stationers' Register records, including Moseley's list, and cannot be regarded as possessing an independent authority. John Freehafer, however, has made a strong argument to the contrary (Greg, "Bakings of Betsy"; Freehafer; see also '''[[Warburton's List]]'''). | W. W. Greg argued that Warburton may not have possessed the manuscripts that he claims to have lost. His list, argues Greg, derived from Stationers' Register records, including Moseley's list, and cannot be regarded as possessing an independent authority. John Freehafer, however, has made a strong argument to the contrary (Greg, "Bakings of Betsy"; Freehafer; see also '''[[Warburton's List]]''').<br><br> | ||

Henry Glapthorne is one of the unsung journeymen of Caroline drama. His six surviving plays include comedy, tragicomedy, and the tragedy ''[[Parricide, The / Revenge for Honour|Revenge for Honour/The Parricide]]''; his playwriting career seems to have extended from around 1630 to around 1640, and to have involved a range of companies including the King's Men, Queen Henrietta's Men, and Beeston's Boys. His surviving work tends towards the derivative and repetitive, but that does not make it uninteresting: indeed, Julie Sanders comments that "Glapthorne's plays have slipped from notice but they remain strong examples of Caroline drama and of the age's sensibility and taste." <br><br> | Henry Glapthorne is one of the unsung journeymen of Caroline drama. His six surviving plays include comedy, tragicomedy, and the tragedy ''[[Parricide, The / Revenge for Honour|Revenge for Honour/The Parricide]]''; his playwriting career seems to have extended from around 1630 to around 1640, and to have involved a range of companies including the King's Men, Queen Henrietta's Men, and Beeston's Boys. His surviving work tends towards the derivative and repetitive, but that does not make it uninteresting: indeed, Julie Sanders comments that "Glapthorne's plays have slipped from notice but they remain strong examples of Caroline drama and of the age's sensibility and taste." <br><br> | ||

Until 2015, this play had never attracted any critical attention at all beyond a bare listing. This is all the stranger since a tragedy entitled "The Duchess of…" will inevitably be in some sort of dialogue with one of the enduring successes of the early modern stage, Webster's ''The Duchess of Malfi''. <br><br> | Until 2015, this play had never attracted any critical attention at all beyond a bare listing. This is all the stranger since a tragedy entitled "The Duchess of…" will inevitably be in some sort of dialogue with one of the enduring successes of the early modern stage, Webster's ''The Duchess of Malfi''. <br><br> | ||

In research arising from the LPD, Steggle attempts to identify the eponymous heroine by investigating the ducal family history. He observes: | In research arising from the LPD, Steggle attempts to identify the eponymous heroine by investigating the ducal family history. He observes: | ||

:The problem is that there is nothing obviously tragic about any of the wives of the Dukes of Fernandina… However, even the most superficial investigation of the dynasty's history discovers one family member whose career certainly was the stuff of Websterian tragedy. This was Leonor de Garcia Álvarez de Toledo y Colonna-de' Medici (1553-1576), the daughter of the first Duke of Fernandina, and one of the leading women of her adopted city of Florence until her death at the hands of her own husband Pietro de Medici. In succeeding centuries, Leonor de Garcia de Toledo has been the eponymous subject of at least four tragedies, two of them operas. In default of further evidence about the "real" Duchesses of Fernandina, there is a possibility that Glapthorne's Duchess might have been the first Duke's daughter. ( | :The problem is that there is nothing obviously tragic about any of the wives of the Dukes of Fernandina… However, even the most superficial investigation of the dynasty's history discovers one family member whose career certainly was the stuff of Websterian tragedy. This was Leonor de Garcia Álvarez de Toledo y Colonna-de' Medici (1553-1576), the daughter of the first Duke of Fernandina, and one of the leading women of her adopted city of Florence until her death at the hands of her own husband Pietro de Medici. In succeeding centuries, Leonor de Garcia de Toledo has been the eponymous subject of at least four tragedies, two of them operas. In default of further evidence about the "real" Duchesses of Fernandina, there is a possibility that Glapthorne's Duchess might have been the first Duke's daughter. (148) | ||

Leonor de Garcia de Toledo was brought up in the Medici family in Florence, alongside her cousins including Francesco (1541-87), Isabella (1542-76), and her future husband Pietro (1554-1604). Like Isabella, she was murdered by her jealous husband, who according to one contemporary account strangled her with a dog lead. Francesco and Isabella feature, of course, as leading characters in Webster's ''The White Devil''. If this suggestion about the play's subject-matter were tenable, then ''The Duchess of Fernandina'' would become a play which relates to Webster not merely in its title, in dialogue with ''The Duchess of Malfi'', but in its subject-matter, very close to that of ''The White Devil''. | Leonor de Garcia de Toledo was brought up in the Medici family in Florence, alongside her cousins including Francesco (1541-87), Isabella (1542-76), and her future husband Pietro (1554-1604). Like Isabella, she was murdered by her jealous husband, who according to one contemporary account strangled her with a dog lead. Over the years, the story has been frequently been dramatized as a tragedy, with at least five versions in nineteenth-century Italy including that of Guiseppe Pieri cited below. Leonor is often the eponymous title character. | ||

<br> | |||

<br>A play about Leonor would be one of a group of Renaissance tragedies exploring the lurid mythos of Florence and the Medicis. In particular, Francesco de Medici and Isabella de Medici feature, of course, as leading characters in Webster's ''The White Devil''. If this suggestion about the play's subject-matter were tenable, then ''The Duchess of Fernandina'' would become a play which relates to Webster not merely in its title, in dialogue with ''The Duchess of Malfi'', but in its subject-matter, very close to that of ''The White Devil''. | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

== For what it's worth == | == For what it's worth == | ||

Information welcome. | Information welcome. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==Works Cited== | ==Works Cited== | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Freehafer, John. "John Warburton's Lost Plays", ''Studies in Bibliography'' (1970) 154-164. </div><div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Greg, W. W. “The Bakings of Betsy.” ''The Library'', 3rd series. 7.11 (1911): 225-259. Print. </div><div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Sanders, Julie. ‘Glapthorne, Henry (bap. 1610)’, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10796]. </div><div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Steggle, Matthew. ''Digital Humanities and the Lost Drama of Early Modern England: Ten Case Studies''. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Freehafer, John. "John Warburton's Lost Plays", ''Studies in Bibliography'' (1970) 154-164. </div><div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Greg, W. W. “The Bakings of Betsy.” ''The Library'', 3rd series. 7.11 (1911): 225-259. Print. </div><div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> | ||

Pieri, Guiseppe, and Francesco Coletti. ''Eleanora di Toledo: tragedia domestica in quattro atti''. Firenze: Romei, 1862. [https://books.google.com.au/books?id=2WdLAAAAcAAJ Google Books].</div> | |||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Sanders, Julie. ‘Glapthorne, Henry (bap. 1610)’, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10796]. </div><div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em"> Steggle, Matthew. ''Digital Humanities and the Lost Drama of Early Modern England: Ten Case Studies''. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015.</div> | |||

[[category:all]] [[Category:Unknown]] [[Category:Warburton's List]][[category:Matthew Steggle]] [[category:Italy]][[category:Florence]][[category:Henry Glapthorne]][[category:murder]] | [[category:all]] [[Category:Unknown]] [[Category:Warburton's List]][[category:Matthew Steggle]] [[category:Italy]][[category:Florence]][[category:Henry Glapthorne]][[category:murder]][[category:LPD-derived publications]] | ||

<br><br> | <br><br>[[category:British Library]] | ||

Page created and maintained by [[Matthew Steggle]], Sheffield Hallam University. | Page created and maintained by [[Matthew Steggle]], Sheffield Hallam University. Updated 19 April 2017. | ||

Latest revision as of 05:02, 1 August 2018

Henry Glapthorne (c.1633-1642)

Historical Records

Stationers' Register

On 29 June, 1660, the printer Humphrey Moseley entered on the Stationers' Register a list of twenty-six plays, including:

- The Vestall. a Tragedy. [brace]

- The noble Triall. a Tragicomedy [brace] by Hen: Glapthorne.

- The Dutchesse of Fernandina. a Tragedy [brace]

- (Greg, BEPD, 1.68)

Warburton's List

Among the manuscript plays which Warburton claimed had been destroyed by his cook are listed:

- The Dutches of Fernandina T. Hen. Glapthorn

- (Greg, "Bakings", 252-9)

- (British Library, Lansdowne MS 807, fo.1r. Reproduced by permission of the British Library. Click image to view full page; click here for more information on Warburton's list)

Theatrical provenance

Unknown. Glapthorne is known to have been active throughout the 1630s, for a range of different dramatic companies (see below). The date range given above is from Harbage.

Probable genres

Tragedy (per Stationers' Register entry).

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

Fernandina, modern Cuba, gained its first Duke in 1559, although there is no evidence that any of the early Dukes resided there. The first Duke of Fernandina was the Spanish grandee, Don García Álvarez de Toledo y Osorio (1514-1577), fourth Marquis of Villafranca del Bierzo. By the time that Glapthorne was writing, Don Garcia had been succeeded, first by his son Pietro, and then by Pietro's son Garcia, third Duke of Fernandina. Thus, if this play is historical, there is a fairly limited selection of family history available to provide Glapthorne's source material. For a more specific suggestion, see "Critical Commentary" below.

References to the Play

None known.

Critical Commentary

"Moseley's entire list of 29 June 1660 is a curious one", comments Bentley (4.493-4), observing that most of the plays on it have disappeared.

W. W. Greg argued that Warburton may not have possessed the manuscripts that he claims to have lost. His list, argues Greg, derived from Stationers' Register records, including Moseley's list, and cannot be regarded as possessing an independent authority. John Freehafer, however, has made a strong argument to the contrary (Greg, "Bakings of Betsy"; Freehafer; see also Warburton's List).

Henry Glapthorne is one of the unsung journeymen of Caroline drama. His six surviving plays include comedy, tragicomedy, and the tragedy Revenge for Honour/The Parricide; his playwriting career seems to have extended from around 1630 to around 1640, and to have involved a range of companies including the King's Men, Queen Henrietta's Men, and Beeston's Boys. His surviving work tends towards the derivative and repetitive, but that does not make it uninteresting: indeed, Julie Sanders comments that "Glapthorne's plays have slipped from notice but they remain strong examples of Caroline drama and of the age's sensibility and taste."

Until 2015, this play had never attracted any critical attention at all beyond a bare listing. This is all the stranger since a tragedy entitled "The Duchess of…" will inevitably be in some sort of dialogue with one of the enduring successes of the early modern stage, Webster's The Duchess of Malfi.

In research arising from the LPD, Steggle attempts to identify the eponymous heroine by investigating the ducal family history. He observes:

- The problem is that there is nothing obviously tragic about any of the wives of the Dukes of Fernandina… However, even the most superficial investigation of the dynasty's history discovers one family member whose career certainly was the stuff of Websterian tragedy. This was Leonor de Garcia Álvarez de Toledo y Colonna-de' Medici (1553-1576), the daughter of the first Duke of Fernandina, and one of the leading women of her adopted city of Florence until her death at the hands of her own husband Pietro de Medici. In succeeding centuries, Leonor de Garcia de Toledo has been the eponymous subject of at least four tragedies, two of them operas. In default of further evidence about the "real" Duchesses of Fernandina, there is a possibility that Glapthorne's Duchess might have been the first Duke's daughter. (148)

Leonor de Garcia de Toledo was brought up in the Medici family in Florence, alongside her cousins including Francesco (1541-87), Isabella (1542-76), and her future husband Pietro (1554-1604). Like Isabella, she was murdered by her jealous husband, who according to one contemporary account strangled her with a dog lead. Over the years, the story has been frequently been dramatized as a tragedy, with at least five versions in nineteenth-century Italy including that of Guiseppe Pieri cited below. Leonor is often the eponymous title character.

A play about Leonor would be one of a group of Renaissance tragedies exploring the lurid mythos of Florence and the Medicis. In particular, Francesco de Medici and Isabella de Medici feature, of course, as leading characters in Webster's The White Devil. If this suggestion about the play's subject-matter were tenable, then The Duchess of Fernandina would become a play which relates to Webster not merely in its title, in dialogue with The Duchess of Malfi, but in its subject-matter, very close to that of The White Devil.

For what it's worth

Information welcome.

Works Cited

Page created and maintained by Matthew Steggle, Sheffield Hallam University. Updated 19 April 2017.