Estrild: Difference between revisions

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

'''Greg''', in the context of examining three manuscript notes by Sir George Buc, reviewed the contributions of John Payne Collier to scholarly awareness of Buc's note on the title page of one of five surviving copies of ''Locrine.'' He credited Collier with having been the "earliest informant"of Buc's note, which he also "reproduced, evidently in hand-traced facsimile," without the heading (312). Greg was primarily concerned with whether the Buc note was a Collier forgery, and he decided that it was not. In the course of his examination of the note, Greg claimed to have transcribed it accurately (in a note, he says, "None of the previous attempts are reliable" [314]). He closed with musings on the truth quotient in Buc's note on the ''Locrine'' title page: "Buc was in an excellent position to ascertain the authorship of contemporary drama. ... Was he correct in his conjecture—for it is nothing more—that Charles Tilney's ''Estrild'' was identical with W. S.'s ''Locrine''?" (319-20). Greg decided to let "literary historians .. thresh out" that question (320). However, as a note to his statement about Buc's authority in identifying Tilney's authorship, Greg pointed to the uncertain date of Buc's note, observing that if it were early, Buc had no "connextion with the Revels Office" then, and if it were late, "that [Buc] died insane" (319, n.2). | '''Greg''', in the context of examining three manuscript notes by Sir George Buc, reviewed the contributions of John Payne Collier to scholarly awareness of Buc's note on the title page of one of five surviving copies of ''Locrine.'' He credited Collier with having been the "earliest informant"of Buc's note, which he also "reproduced, evidently in hand-traced facsimile," without the heading (312). Greg was primarily concerned with whether the Buc note was a Collier forgery, and he decided that it was not. In the course of his examination of the note, Greg claimed to have transcribed it accurately (in a note, he says, "None of the previous attempts are reliable" [314]). He closed with musings on the truth quotient in Buc's note on the ''Locrine'' title page: "Buc was in an excellent position to ascertain the authorship of contemporary drama. ... Was he correct in his conjecture—for it is nothing more—that Charles Tilney's ''Estrild'' was identical with W. S.'s ''Locrine''?" (319-20). Greg decided to let "literary historians .. thresh out" that question (320). However, as a note to his statement about Buc's authority in identifying Tilney's authorship, Greg pointed to the uncertain date of Buc's note, observing that if it were early, Buc had no "connextion with the Revels Office" then, and if it were late, "that [Buc] died insane" (319, n.2). | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

'''Maxwell''', acknowledging that the title page of ''Locrine'' implies strongly that the play had been "reworked or revised," added that the "original need not have been an old play" (26). He reviewed the sources of ''Locrine,'' which would necessarily have been the sources of "Estrild," whatever the authorial link between the two plays might have been. He credited Theodor Erbe in ''Die Locrinesage und die Quellen des pueudo-Shakespeareschen Locrine'' with a "comprehensive study" of the uses of Geoffrey of Monmouth, Caxton, and Holinshed by the author of ''Locrine'', but noted that Erbe had "overlooked" ''The Mirror of Magistrates'' as source (27). Endorsing the use of that source (as explored by Willard Farnham, "John Higgins' 'Mirror' and 'Locrine'," ''Modern Philology'' 23.3 [1926]: 307-313), Maxwell offered an additional source for two scenes featuring Estrild: Thomas Lodge's "Complaint of Elstred," printed in 1593, in the collection entitled ''Phillis'' (33). The composition date of Lodge's complaint is not known, but Maxwell thought it more likely that the author of ''Locrine'' "knew it in its printed form" (38). As his argument moved into a discussion of Robert Greene in relation to authorship of ''Selimus'' and ''Locrine,'' Maxwell claimed that "it is not of real importance to my thesis that the reviser of ''Locrine'' be recognized as indebted to Lodge's poem" (68). However, for the authorship of "Estrild," that debt is crucial; further, the link requires that Lodge's complaint be written and in circulation | '''Maxwell''', acknowledging that the title page of ''Locrine'' implies strongly that the play had been "reworked or revised," added that the "original need not have been an old play" (26). He reviewed the sources of ''Locrine,'' which would necessarily have been the sources of "Estrild," whatever the authorial link between the two plays might have been. He credited Theodor Erbe in ''Die Locrinesage und die Quellen des pueudo-Shakespeareschen Locrine'' with a "comprehensive study" of the uses of Geoffrey of Monmouth, Caxton, and Holinshed by the author of ''Locrine'', but noted that Erbe had "overlooked" ''The Mirror of Magistrates'' as source (27). Endorsing the use of that source (as explored by Willard Farnham, "John Higgins' 'Mirror' and 'Locrine'," ''Modern Philology'' 23.3 [1926]: 307-313), Maxwell offered an additional source for two scenes featuring Estrild: Thomas Lodge's "Complaint of Elstred," printed in 1593, in the collection entitled ''Phillis'' (33). The composition date of Lodge's complaint is not known, but Maxwell thought it more likely that the author of ''Locrine'' "knew it in its printed form" (38). As his argument moved into a discussion of Robert Greene in relation to authorship of ''Selimus'' and ''Locrine,'' Maxwell claimed that "it is not of real importance to my thesis that the reviser of ''Locrine'' be recognized as indebted to Lodge's poem" (68). However, for the authorship of "Estrild," that debt is crucial; further, the link requires that Lodge's complaint be written and in circulation in time for Charles Tilney to have consulted it for his "Estrild," ''c''. 1585. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

'''Berek''' | '''Berek''' | ||

Revision as of 12:24, 11 August 2015

Charles Tilney (c. 1585)

Historical Records

Buc's note

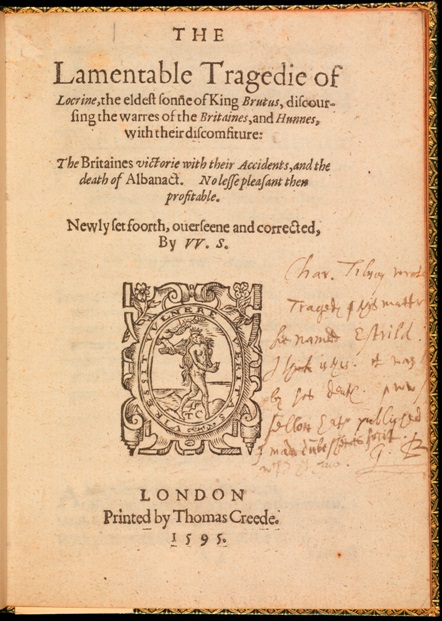

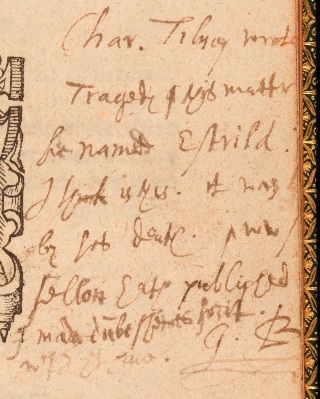

An undated note in the hand of Sir George Buc on the title page of one of five surviving copies of Locrine (printed 1595) reads:

Char. Tilney wrote <a>

Tragedy of this mattr <wch>

hee named Estrild: <& wch>

J think is this. It was l<lost ?>

by his death. & now [?] s<ome ? >

fellow hath published <it.>

J made the dūbe shewes for it.

wch J yet have. G. B<.>.

|

|

Buc signature on the title page of Locrine; reproduced with permission from the Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cologny, Geneve.

Theatrical Provenance

Unknown; information welcome.

Probable Genre(s)

Tragedy

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

The story would have to be a pseudo-biography of Estrildis, daughter of the King of Germany, in the time of the war between Brute, first king of the Britons, versus Humber, King of the Huns, c. 1115-1075. B.C.E. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, Estrildis was one of three captives aboard the ship of Humber, which held the spoil of Humber's recent conquests in Germany. Locrine, eldest son of Brute, defeated Humber in battle (Humber fled and drowned in the River Humber). Locrine then pillaged Humber's ships and claimed the girls. It was Estrildis who set him on fire, however: "so fair was she that scarce might any be found to compare with her for beauty, for no polished ivory, nor newly-fallen snow, nor no lilies could surpass the whiteness of her flesh" (Sacred Text).

A more recent version of Estrild's story than Geoffrey of Monmouth's is in The Mirror of Magistrates, as expanded in 1574 by John Higgins. (tbc)

References to the Play

The only surviving reference to "Estrild" is Buc's note (See Historical Records.)

Critical Commentary

The context for discussion of "Estrild" by scholars is the anonymous play, Locrine, initially in regard to Buc's handwritten note on the title page of one copy of the 1595 printing of Locrine and subsequently in regard to its having been an analogue for, or early version of Locrine somehow revised into and absorbed by the author of the extant play.

Collier, in Catalogue of Early English Literature at Bridgewater House (1837), described the Buc note on the title page of Locrine (41); he added to that description in 1865 in Bibliographical Account of Early English Literature by providing a biographical blurb on Charles Tilney as well as asserting that "the authorship of "Locrine," false imputed to Shakespeare, is thus decided" (i.93-5, esp. 95).

Fleay knew of Buc's note, because he quotes Richard Simpson (without citation) as misattributing Locrine to Charles Tilney, whose name occurs in this matter only in the Buc note(BECD, 2.321))

Chambers knew of Collier's comments on Buc's note, indicating Tilney's authorship of Locrine; but, skeptical generally of Collier's claim and persuaded by other evidence, Chambers inclined to date Locrine in 1591. He did, however, allow that the extant text might be "a very substantial revision" (4.27).

Greg, in the context of examining three manuscript notes by Sir George Buc, reviewed the contributions of John Payne Collier to scholarly awareness of Buc's note on the title page of one of five surviving copies of Locrine. He credited Collier with having been the "earliest informant"of Buc's note, which he also "reproduced, evidently in hand-traced facsimile," without the heading (312). Greg was primarily concerned with whether the Buc note was a Collier forgery, and he decided that it was not. In the course of his examination of the note, Greg claimed to have transcribed it accurately (in a note, he says, "None of the previous attempts are reliable" [314]). He closed with musings on the truth quotient in Buc's note on the Locrine title page: "Buc was in an excellent position to ascertain the authorship of contemporary drama. ... Was he correct in his conjecture—for it is nothing more—that Charles Tilney's Estrild was identical with W. S.'s Locrine?" (319-20). Greg decided to let "literary historians .. thresh out" that question (320). However, as a note to his statement about Buc's authority in identifying Tilney's authorship, Greg pointed to the uncertain date of Buc's note, observing that if it were early, Buc had no "connextion with the Revels Office" then, and if it were late, "that [Buc] died insane" (319, n.2).

Maxwell, acknowledging that the title page of Locrine implies strongly that the play had been "reworked or revised," added that the "original need not have been an old play" (26). He reviewed the sources of Locrine, which would necessarily have been the sources of "Estrild," whatever the authorial link between the two plays might have been. He credited Theodor Erbe in Die Locrinesage und die Quellen des pueudo-Shakespeareschen Locrine with a "comprehensive study" of the uses of Geoffrey of Monmouth, Caxton, and Holinshed by the author of Locrine, but noted that Erbe had "overlooked" The Mirror of Magistrates as source (27). Endorsing the use of that source (as explored by Willard Farnham, "John Higgins' 'Mirror' and 'Locrine'," Modern Philology 23.3 [1926]: 307-313), Maxwell offered an additional source for two scenes featuring Estrild: Thomas Lodge's "Complaint of Elstred," printed in 1593, in the collection entitled Phillis (33). The composition date of Lodge's complaint is not known, but Maxwell thought it more likely that the author of Locrine "knew it in its printed form" (38). As his argument moved into a discussion of Robert Greene in relation to authorship of Selimus and Locrine, Maxwell claimed that "it is not of real importance to my thesis that the reviser of Locrine be recognized as indebted to Lodge's poem" (68). However, for the authorship of "Estrild," that debt is crucial; further, the link requires that Lodge's complaint be written and in circulation in time for Charles Tilney to have consulted it for his "Estrild," c. 1585.

Berek

Griffin

Knutson

Sharpe

Kirwan is not persuaded (as are Berek and Sharpe) that Buc was identifying Locrine as a lost play by Charles Tilney called "Estrild" (133-4).

For What It's Worth

Estrild as a tragic character in Mirror for Magistrates'

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Roslyn L. Knutson, Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated 11 June 2015.