Late Murder in White Chapel, or Keep the Widow Waking

Dekker, Ford, W. Rowley, Webster (1624)

(See also: "Late Murder of the Son upon the Mother")

Historical Records

Dramatic Records of Sir Henry Herbert

There are two records of Herbert's licensing of this play:

- 1624, September. “A new Tragedy, called, A Late Murther of the Sonn upon the Mother: Written by Forde, and Webster.” (S. A. 218-219.)

- (Herbert 29)

- (Adams [Herbert 29n]: “The day of the month is not given, but presumably it lay between the third and the fifteenth. Presumably, also, the play was licensed to the Cockpit Company, mentioned in the immediately preceding entry.”)

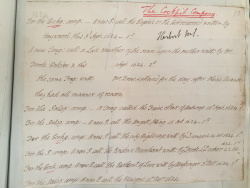

J. O. Halliwell-Phillips transcribed a number of Sir Henry Herbert's licensing records and compiled them in various scrapbooks now held at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Amongst them is the following transcription of plays from September 1624:

A new Trag: call: a Late Murther of the sonn upon the mother writt: by Mr

- Forde Webster & this Sept. 1624. 2li.

- The same Trag: writt: Mr. Drew & allowed for the day after theirs because

- they had all manner of reason.

(NB. Bentley notes that the fee paid was "double the one usual at this time for licensing a new play. This double fee may be explained by an unusually large number of alterations or by the difficulties suggested by the licence of a second play on the subject by Drew. I take this second licence—which was not copied by Chalmers or Malone—to indicate that two different companies prepared plays on this topical subject at the same time; that Herbert, after hearing arguments, allowed both plays so that they could be acted in competition; that for unspecified reasons he allowed the Dekker, Rowley, Ford, and Webster play a one-day advantage. … [I]t is clear that the subject was thought to have great appeal and that two London companies were competing for the right to exploit it." Bentley 3.253-54).

Star Chamber Proceedings

“The Answer of Thomas Dekker one of the Defend(an)ts,” 3 February 1625 (reproduced in Sisson 256-57):

and whereas in the sayd Information, Mention is made of a Play called by the name of Keepe the Widow waking, this Defendt sayth, that true it is, Hee wrote two sheetes of paper conteyning the first Act of a Play called The Late Murder in White Chappell, or Keepe the Widow waking, and a speech in the Last Scene of the Last Act of the Boy who had killed his mother wch Play (as all others are) was licensed by Sr Henry Herbert knight, Mr of his Maties Reuells, authorizing thereby boeth the Writing and Acting of the sayd Play. (qtd. in Sisson 257)

“Deposition of Thomas Dekker,” 24 March 1625 (reproduced in Sisson 258-59):

Dekker testified “that John Webster . . . Willm Rowly John ffoord and this deft were privy consenting & acquainted wth the making & contriuing of the sd play called keep the widow waking and did make & contrive the same vppon the instruccons giuen them by one Raph Savage And this deft saith that he this deft did often see the said play or pt thereof acted but how often he cannot depose” (qtd. in Sisson 258).

He describes vaguely “some passage acted in the said play about the getting of a lycense for the mariage of the widow there personated” (qtd. in Sisson 258) and admits that “he doth remember that in a play called keepe the widow waking acted at the Red bull a boy did come in [wth a we] wenches apparel and tell the [said Anne] widow [psonated in the] represented in the sd play that he had brough her a Basket of Apricocks from one of her tennts wherevppon one knocking wth a pot the said boy cried anon anon Sr” (qtd. in Sisson 258).

Bill of Information, Star Chamber Suit against Audley

Excerpt, quoted in Sisson 234:

- …the said Rowley, dickers, & … Hodskyns did most vnlawfully & libellouslye to the great scandal & disgrace of … Anne Elsden make devise & contrive one scandalous enterlude or play most tauntinglye naming the same enterlude or play Keepe the widdowe wakeinge thereby setting forth and intymateing how long … Ann Elsden was kept wakeinge, and the maner of … Anne Elsdens distempature wth wyne and hott waters and the losse of her estate … to the great infamy & scandal of … Anne Elsden.

Theatrical Provenance

“Prince’s (lic. Sept)” (Harbage); “There is some uncertainty about the company which occupied the Red Bull in September 1624, but it was probably Prince Charles’s (I) company” (Bentley III.255-56); Acted at the Red Bull in the autumn of 1624 (Sisson 42, Wright 633); “seuerall tymes acted & played at the playhouse called the Bull at Clarkenwell in the Countye of Middlesex by the players there” (Bill of Information in the Star Chamber Suit against Audley and others, qtd in Sisson 236).

Probable Genre(s)

Comedy & Tragedy (Harbage); topical drama; domestic tragedy.

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

- 2. Julij 1624 Richard Hodgkins. The repentance of NATHANAEL TINDALL that kil(le)d his mother . . . vjd.

- (qtd. in Sisson 57)

- 16 Septembris 1624 John Trundle Richard Hodgkins. Entred for their Copie vnder the handes of master DOCTOR WORRALL and master Lownes Warden. . . . A most bloudy vnnaturall, and vnmatchable murther Comitted in Whitechappell by NATHANAELL TINDALL vpon his owne mother written by JOHN MORGAN . . vjd.

- (qtd. in Sisson 57)

Vickers provides a recent, concise summary based on the likely source material:

- This play was based on two contemporary London scandals, one comic and one tragic. The comic element recounted the true story of how an unscrupulous suitor kept a rich old widow in a state of drunkenness and sleeplessness until she went through a marriage ceremony with him in a London tavern, at which point he robbed her of everything he could. The tragic story told how a young boy killed his mother, confessed the crime, and was hanged. (314)

The fullest treatment of the subject matter comes from Sisson, however. There exists an unusually large amount of historical evidence to assist in reconstructing the subject matter of the play, which Sisson attempts to do in great detail, supplementing the Star Chamber Proceedings information with “the records of the Middlesex Sessions, now in the Middlesex Guildhall in Westminster”; records which “help to complete the story on which the comic part of the play was founded, and furnish most of the information concerning the murder which was related in its tragic plot” (43). The following information comes from Sisson’s two-part article of the same name in the 1927 edition of The Library (pp. 39-57 & 233-59).

“Comic” plot: The story of Anne Elsdon and Tobias Audley

This plot, Sisson suggests, involved the 62 year old widow Anne Elsdon (who lived “not far from the Red Bull Theatre in St. John Street, Clerkenwell”) and the advances of the considerably younger (25 year old) widower Tobias Audsley, whose “motive was clear enough” (“local gossip credited [Anne] with an estate of £6,000 in all,” 45). Sisson reconstructs events from the historical records:

About eight o’clock on the evening of Wednesday, 21 July 1624, Anne Elsdon accompanied by her friend Martha Jackson, aged 40, the wife of a shoemaker, went with Audley on his invitation to the Greyhound Tavern. They were shown into a private room, and found there awaiting them a motley company which included two disreputable ministers of religion, Nicholas Cartmell and Francis Holiday, and two women of easy virtue, Mary Spenser of Charterhouse Lane, of the junior branch of her profession, and her ‘Nurse’, as she calls her, Margery Terry. Anne and Martha were plied generously with drink, and it was hoped that Anne would declare before witnesses that she would accept Audley as her husband and so contract herself to him. All present were in the plot and were to profit from the resulting marriage… (46)

Anne was detained “three days and nights in a constant state of drunkenness” (46), and eventually “drugs were sent for and used by Cartmell” (47) and a wedding licence was obtained on Friday 23 July (see Sisson 47 for the licence). After numerous setbacks, the marriage eventually took place, although “Anne was evidently in a state of alcoholic coma” (48) and would later protest that she was not Audley’s wife.

Audley, now believing himself entitled to Anne’s fortune, was soon arrested at the request of Anne’s son-in-law, Garfield, but bailed almost immediately via the assistance of Audley’s brother, John. Audley began to raid Anne’s house for valuables; Anne remained detained at a tavern (the Nag’s Head) where several witnesses would later testify that they had heard her protesting her imprisonment (50). Garfield and his wife (Anne’s daughter) began looking for Anne, who was (as a result) relocated to detention at the Bell Tavern in Wood Street (50). Anne was returned to her house on the Monday night, and as Sisson notes, “[i]t is difficult to be sure what Audley had gained”:

The prosecution alleged that he had carried off £3,000 worth of documents, and doubtless Anne’s securities were dealt in to some extent. He had taken £120 in cash, and a good deal of plate. But the tavern expenses for the five days’ revels were heavy, £50 in all. He was also committed to share out over £300 to the conspirators, and doubtless their demands were the first to be satisfied. Garfield deposed that Audley in the space of five weeks had wasted the whole of Anne’s personal estate, £1,000, and was trying to borrow money. (51)

In the aftermath “[d]issensions among the thieves broke out early” (51) and on August 8 Audley was involved in a violent altercation at Garfield’s house whilst trying to see Anne (presumably in pursuit of financial claims) (51).

Various conspirators were charged and then acquitted of arranging an unlawful marriage between Audley and Anne:

- Garfield perceived that his charges against his enemies under the Common Law were not effective, one after another charge failing. The whole question had been further complicated by the play and ballad. He therefore took the matter to the Court of Star Chamber, and laid an Information there, which the Attorney-General sponsored. The Bill of Information is dated 26 November. The Answers of Audley and his friends are dated 10 December, and those of the theatre people involved from Dekker’s on 3 January to Holland’s on 5 February. (54)

The chief players in these events died whilst the case was at trial: “It is likely that the Star Chamber trial died of protraction, and that Garfield’s desire for vengeance faded, with the impossibility of recovering the lost goods, and with the death of the principal offender, Audley” (55).

“Tragic” plot: The murder of Joan Tindall by her son, Nathaniel Tindall

From the records of the Middlesex Sessions, Sisson establishes that “Nathaniel Tindall or Grindall, of Whitechapel, yeoman, murdered Joan Tindall or Grindall on 9 April 1624 in Whitechapel. He came to trial at the Old Bailey at the Gaol Delivery from Newgate, along with Tobias Audley, on Friday, 3 September” (55). The motive was unknown, and there was no record of a Coroner’s Inquest.

Two ballads on the subject were recorded in the Stationers’ Register (see “Historical records” above): “The documents give us very little information about the handling of this tragic story in the play. Of the two ballads, the first only is extant, and it gives no information about the crime” (57).

The extant ballad is The penitent Sonnes Teares, for his murdered Mother (EEBO-TCP, Open-Access), purportedly by “Nathaniel Tyndayle, sicke both in soule and body: a prisoner now in New-gate” (57).

References to the Play

Ballad: “keeping the widow wakeing of lett him that is poore and to wealth would aspire get some old rich widdowe and grow wealthye by her, to the tune of the blazing torch” (reproduced in Sisson 238-40, Panek 109-110):

- And you whoe faine would heare the full

- discourse of this match making,

- The play will teach you at the Bull,

- to keepe the widow wakeing.

- (qtd. in Sisson 240)

Bentley discusses the ballad, summarising Sisson 248-51: “Several parties or witnesses in the actions testify that this ballad was sung on the streets, one says that boy actors from the theatre pointed to Anne Elsden’s windows and said, ‘there dwelte the widdowe waking’, and Benjamin Garfield, Mrs. Elsden’s son-in-law, said that the ballad-monger not only sang it under Mrs. Elsden’s window but when brought before a Justice of the Peace testified that ‘he was purposely sent thither to singe the said ballad by one Holland’, i.e. Aaron Holland, who built the Red Bull theatre and was an important partner in the enterprise for a number of years” (III.255).

Critical commentary

In the second part of his article (233-59), Sisson moves away from reconstructing the historical event of the Audley-Elsdon marriage and concentrates on the play:

- It is abundantly evident, from the ballad, from the title of the play, and from Garfield’s accusations, that the story of the marriage was treated in a facetious manner, with satirically frank insistence upon an old widow’s appreciation of the attentions of a young husband and upon her convivial tendencies. The persons of the drama presumably included the three unsuccessful suitors, the broker, the horse-courser, and the comfit-maker, as well as Toby Audley, who is easily recognizable as a tobacco seller. The Lawyer is probably Edmond Ward, who described himself to the Middlesex Justices as ‘of the Inner Temple’, though he is not to be found in its records. The priest is obviously Nicholas Cartmell. … Garfield probably was not brought upon the stage as the son-in-law. He was possibly merged into one of the suitors. With this modification of status, his anger at the marriage could be readily fitted into the comedy, and it may be imagined that an actor could make up to resemble him closely enough to add zest to the impersonation.

- We may assume that the play concludes with the success of the plot, the widow making the best of a bad bargain, as many a deceived bride or bridegroom has to do in Elizabethan plays. The moral appears to be that poor young men should try to follow in Audley’s cozening footsteps. … Audley was undoubtedly the hero of the plot, a young apprentice-gallant who scored off the Philistines. (241-42)

Sisson further infers the action of two scenes of the play from Dekker’s testimony about them: “Audley and Hide discussing the procuring of the licence of marriage,” in which “Audley in a vein of mirth narrates how he told the officials ‘that it was for an old bedd ridden woman and a young fellow together’,” and a tavern scene in which the widow is drinking with Audley and “a drawer enters, dressed as a girl, with an empty basket, pretending to bring in a basket of apricots from one of the widow’s tenants as a present for her” (242).

Adams (“Hill’s List” 81-82) discusses the play when considering an entry for The Wrong’d Widow’s Tragedy in Abraham Hill’s list of play manuscripts: “One might be tempted to identify it [Wrong’d Widow] with the lost Keep the Widow Waking . . . but the portion of that play relating to the widow (who was in truth most grievously wronged) seems to have been treated in a wholly comic spirit. It may be noted, however, that the play had also a serious part involving a murder in Whitechapel, and was actually licensed by Herbert, September 1624, under the title ‘A New Tragedy, called A Late Murther of the Sonn upon the Mother’.”

Wright (excerpt): “Occasionally the domestic drama so accurately described a contemporary event that it created a scandal, as was true of a lost play, The Late Murder in Whitechapel, or Keep the Widow Waking, by Dekker, William Rowley, Ford, and Webster, an arrant piece of scandal-mongering acted at the Red Bull in 1624. The ingenious authors put into one play the separate elements of a local murder and the forced marriage of an old widow who lived almost within earshot of the Red Bull.” (633).

Harrison notes that “Mrs. Elsdon . . . was not the first widow to be so served and apparently the phrase ‘Keep the widow waking’ was popular at least thirty years before [the lost play]” (97). Harrison reconstructs (from extant pamphlets and ballads, and titles of lost ballads) the story of a tripe-wife widow, Mrs Mescall, who was similarly plied with wine for the purpose of procuring a promise of marriage from her.

Clark has recently commented on the playwrights’ response to historical events in the crafting of the “comic” plot: “What is hard to comprehend is the attitude of the collaborative playwrights and of balladeer Richard Hodgkins. That attitude is blatant in his lines that advise “keeping the widow wakeing or lett him that is poore and to wealth would aspire / get some old rich widdowe and grow wealthye by her,” in charges of malicious defamation brought by the widow’s son-in-law, and in depositions taken for a trial never held. Wasting a widow in order to marry her and waster her holdings provided a scenario that apparently was considered imitable and laughable, not reprehensible and lamentable: the perpetrator provided a model, the widow a butt” (402).

Like most critics, Hanson cannot fathom the reasons for casting the Elsdon-Audley story as the “comic” plot:

- This horrifying little story and the lost play based on it suggest the complexity of the social semantics that surround both the widow and the prodigal. … The reasons for the play's composition are obscure; the evidence for its existence are a jolly ballad advertisement and the legal records of the attempt by Ellsden's son-in-law to have it suppressed because of the pain it caused the already severely traumatized Ellsden. Thus we are left to wonder why several of the period's most important playwright's, including those responsible for Moll Cutpurse and the Duchess of Malfi, thought this story of brutality to an old woman would appeal to an audience. One possible explanation is afforded by the nature of the property Audley stole from Ellsden, which included bonds and deeds valued at three thousand pounds, indicating that she was likely a moneylender. The ballad indicates that the play handles the matter as a jest, celebrating Audley for his cleverness. Ellsden is barely characterized; she is duped while drunk, and while this suggests intemperance, her lust is not emphasized save in her husband's final admonition not to complain because “Ile be a comfort all thy life / a nights to keepe the waking.” Thus we might conjecture that the play was a farce, continuous in spirit with popular disciplinary practices such as the skimmington ride, fuelled by resentment at Ellsden's financial position and activities (and possibly those of her recently deceased husband), which gave her power at odds with the properly abject position of an elderly woman. But what makes the idea of the play so unsettling is precisely that the situation cannot really have aroused masculine anxiety at the spectacle of female power since Ellsden emerges in the records as so vulnerable and pathetic. Moreover, if the play might have tapped into some primitive sense of justice, the actual agents of the judicial system saw things rather differently, and Audley met a wretched death in prison, no doubt to the satisfaction of the former Beadle of Bridewell. (222-23).

Panek (107-123) revisits and summarises the historical evidence in the context of the lost play (reproducing the two-part ballad from Star Chamber records on pp.109-110; also reproduced in Sisson “Keep the Widow Waking” 238-40 and Sisson Lost Plays 103-06). She suggests that “the play and the ballad work to reduce Anne to the familiar figure of the lusty widow, and thereby to empower Audley through disempowering her” (118). Panek further considers the “sexualisation of the widow” in bed-scenes from the play:

- It the number of times Anne’s character “went to bed” in the play approached the defendants’ emphasis on that activity, the scene in which Audley’s character explains that he needs a license “for the marying of an old bed ridden woman and a young fellowe together” must have lent the phrase “bed-ridden” a decidedly bawdy innuendo. Her desires are also hinted at in the scene where she is offered “apricocks” – a fruit with well-known phallic connotatiosn – by a cross-dressed vintner’s boy. If, as the prosecution alleges, Audley and his companions did indeed enact the original version of this scene for their own amusement at the Nag’s Head before it was imported into the play, the conspirators certainly had a keen enjoyment of the theatrical, and a sense of how it might be used to humiliate. (121)

Unlike most critics, Panek can see a case for how the Elsdon-Audley ‘marriage’ could be made fit for a comic plot, if only in the realm of the theatre (“the public’s approval of fraud is generally confined to the playhouse”), where Anne must have become “the stage figure of the lusty widow, a woman who cannot be wronged by even the most outrageous and aggressive of courtship tactics” (121). (See 107 for an imaginative account of how the Elsdon-Audley material may have been construed for comic purposes).

Vickers refers to the play as an “instructive example of the conditions under which Elizabethan dramatists worked” (314):

- The "marriage" took place in late July 1624, the boy was sentenced to be hanged on 3 September 1624, and in mid-September Sir Henry Herbert, Master of the Revels, licensed a new play on both stories by Dekker, Webster, Rowley, and Ford, to be performed at the Red Bull in Clerkenwell. The coauthors had about six weeks to fulfill the commission, a not-unusual period of time for dramatists who must have worked in permanent haste. The play has perished, but a Star Chamber deposition of 3 February 1625 survives, from a case brought by the widow's son-in-law against the authors of the play and of a scurrilous ballad publicizing the play. The accusation in the Star Chamber suit stated that Rowley, Dekker, and others "'did make devise & contrive one scandalous enterlude or play Keepe the widdowe wakeinge.'" In his Answer, Dekker defined his share in the undertaking, which consisted of "'two sheetes of paper conteyning the first Act'" and "'a speech in the last Scene of the last Act of the Boy who had killed his mother."

- Since those writing or copying plays for the London theater worked with folio-sized paper on separately folded sheets, in units of four pages, Dekker's "two sheets" would have made four leaves or eight pages. Sisson deduced that Dekker wrote the first act on the first six pages and the speech in Act 5 (presumably, the boy's repentant speech before execution) on the last leaf, which could be detached and inserted in its proper place when the manuscript was assembled by the company's bookkeeper, who prepared the prompt copy and the individual parts. The speed with which the play was staged meant that the four dramatists had little time for consultation. (314-15)

Sisson had earlier treated this matter on pp.244-47.

For What It’s Worth

Anne Elsdon died by 24 March 1626, and Audley died before 10 July 1625 (Sisson 54).

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by David McInnis, University of Melbourne; updated, 30 March 2016.

- John Ford

- Thomas Dekker

- William Rowley

- All

- Domestic tragedy

- Forced marriage

- Matricide

- Murder

- Widow

- Ballads

- Star Chamber

- True crime

- Whitechapel

- Herbert's records

- Red Bull

- Prince Charles's (I)

- David McInnis

- Halliwell-Phillips

- Folger

- London

- Collaborations

- Update

- John Webster

- Webster, John

- Dekker, Thomas

- Ford, John

- Rowley, William