Wise Man of West Chester, The: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

===Similar Subject Matter=== | ===Similar Subject Matter=== | ||

From the time Dulwich College put Henslowe's diary into the hands of scholars, theater historians have tried to match titles in Henslowe's records with extant plays on the basis of similar titles and/or subject matter. That not always has been the case with ''Wise Man''. '''Malone''', who first saw Henslowe's manuscript, did not identify ''Wise Man'' with ''John a Kent'', but he probably did not know that ''John a Kent'' existed. Incidentally, Malone misread Henslowe's title as "the wise '''men''' of chester" ([http://www.archive.org/stream/playsandpoemswi18rowegoog#page/n311/mode/2up Malone, 3.304]); subsequent editions of the diary by Collier, Greg, and Foakes | From the time Dulwich College put Henslowe's diary into the hands of scholars, theater historians have tried to match titles in Henslowe's records with extant plays on the basis of similar titles and/or subject matter. That not always has been the case with ''Wise Man''. '''Malone''', who first saw Henslowe's manuscript, did not identify ''Wise Man'' with ''John a Kent'', but he probably did not know that ''John a Kent'' existed. Incidentally, Malone misread Henslowe's title as "the wise '''men''' of chester" ([http://www.archive.org/stream/playsandpoemswi18rowegoog#page/n311/mode/2up Malone, 3.304]); subsequent editions of the diary by Collier, Greg, and Foakes have corrected the reading. '''Collier''' noted that ''Wise Man'' "was a new play" in his 1845 edition of the diary ([http://www.archive.org/stream/diaryphiliphens00hensgoog#page/n82/mode/2up Collier, 45]), but he too probably did not know ''John a Kent'' then. However, in 1851 he published the first edition of ''John a Kent'', exploring thoroughly its provenance, dramatist, and subject matter, yet he did not make a connection to Henslowe's ''Wise Man''. | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

{| cellpadding="5" border="0" class="wikitable" | {| cellpadding="5" border="0" class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 175: | Line 175: | ||

|} | |} | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

:'''Fleay''' appears to be the first to specify a link between the two plays in ''A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama, 1559-1642'' (1891). He entered '' | :'''Fleay''' appears to be the first to specify a link between the two plays in ''A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama, 1559-1642'' (1891). He entered ''Wise Man'' in his list of anonymous plays, noting the purchase of its script by the Admiral's players on 19 September 1601 ([http://www.archive.org/stream/abiographicalch02fleagoog#page/n313/mode/2up Fleay, 2.303]); for further commentary, he referred the reader to the entry for ''John a Kent and John a Cumber''. In that entry, Fleay stated, "I have no doubt that it [''John a Kent''] is the same as ''The Wiseman of West Chester'' produced by the Admiral's men at the Rose 2nd Dec. 1594" ([http://www.archive.org/stream/abiographicalch02fleagoog#page/n125/mode/2up Fleay, 114]). He gave no reason for his lack of doubt. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

:'''Greg''' thought Fleay was "almost certainly right" in making the identification ([http://www.archive.org/stream/henslowesdiary02hensuoft#page/172/mode/2up Greg, II.172]). Greg made the first plausible link between ''Wise Man'' and ''John a Kent'' by assigning an item in Henslowe's 1598 inventory, "Kentes woden leage," to ''Wise Man'' (presumably on the assumption that "West Chester" = "Kent"). Inconveniently for this thesis, the manuscript of ''John a Kent'' has no need for a wooden leg. Therefore Greg suggested that the manuscript might be a revision with the episode of the wooden leg edited out. | :'''Greg''' thought Fleay was "almost certainly right" in making the identification ([http://www.archive.org/stream/henslowesdiary02hensuoft#page/172/mode/2up Greg, II.172]). Greg made the first plausible link between ''Wise Man'' and ''John a Kent'' by assigning an item in Henslowe's 1598 inventory, "Kentes woden leage," to ''Wise Man'' (presumably on the assumption that "West Chester" and/or "wise man" = "Kent"). Inconveniently for this thesis, the manuscript of ''John a Kent'' has no need for a wooden leg. Therefore Greg suggested that the manuscript might be a revision with the episode of the wooden leg edited out. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

:Despite the authority of Fleay and Greg, opinion did not harden into fact. '''St. Clare Byrne''', editor of the Malone Society Reprint of ''John a Kent and John a Cumber'', acknowledged the scholarly interest in linking Munday's play with ''The Wise Man of West Chester'' as well as ''Randal Earl of Chester''. She thought the relationship of the plays, through serial revision, was "by no means impossible" but saw "no secure basis for speculation" (x). | :Despite the authority of Fleay and Greg, opinion did not harden into fact. '''St. Clare Byrne''', editor of the Malone Society Reprint of ''John a Kent and John a Cumber'', acknowledged the scholarly interest in linking Munday's play with ''The Wise Man of West Chester'' as well as ''Randal Earl of Chester''. She thought the relationship of the plays, through serial revision, was "by no means impossible" but saw "no secure basis for speculation" (x). | ||

| Line 185: | Line 185: | ||

:'''Gurr''' is the leading supporter currently of ''Wise Man'' as ''John a Kent''. At least since 1987 he has been renaming the Henslowe play ''The Wise '''Men''' of West Chester'' and indexing it accordingly (''Playgoing in Shakespeare's London'', 140, 152, and 307; see also ''Shakespeare's Opposites'', 317). In ''Shakespeare's Opposities'' he offers a new argument that concerns the book-keeper (or scribe) commonly known as Hand C, whose hand appears in various notations including "prompt-directions" (St. Clare Byrne, vii). According to Gurr, Hand C "belonged" to the Admiral's company in the sense that he was "a loyal worker for Alleyn through more than a decade" (106, n.27). The apparent inference is that Hand C's hand confirms the Admiral's ownership of ''John a Kent'' and thereby strengthens the case that ''Wise Man'' and the Munday play are the same. | :'''Gurr''' is the leading supporter currently of ''Wise Man'' as ''John a Kent''. At least since 1987 he has been renaming the Henslowe play ''The Wise '''Men''' of West Chester'' and indexing it accordingly (''Playgoing in Shakespeare's London'', 140, 152, and 307; see also ''Shakespeare's Opposites'', 317). In ''Shakespeare's Opposities'' he offers a new argument that concerns the book-keeper (or scribe) commonly known as Hand C, whose hand appears in various notations including "prompt-directions" (St. Clare Byrne, vii). According to Gurr, Hand C "belonged" to the Admiral's company in the sense that he was "a loyal worker for Alleyn through more than a decade" (106, n.27). The apparent inference is that Hand C's hand confirms the Admiral's ownership of ''John a Kent'' and thereby strengthens the case that ''Wise Man'' and the Munday play are the same. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

:'''Knutson''' argues for the discrete identity of ''Wise Man''. She is primarily resisting the urge among scholars "on slender evidence or intuition" to identify plays with similar subjects or leading characters as the same or as versions of one another (3). She argues that the habit of adult playing companies to duplicate the successful offerings of their competitors with similar offerings of their own was "a regular feature of competition among the professional companies" (4). She also raises a question about the title of ''Wise Man'': namely, if the Admiral's players had Munday's play in repertory, why did Henslowe ignore the popularity of John a Kent as a folk figure by choosing a title that made the company's wise man anonymous? ( | :'''Knutson''' argues for the discrete identity of ''Wise Man''. She is primarily resisting the urge among scholars "on slender evidence or intuition" to identify plays with similar subjects or leading characters as the same or as versions of one another (3). She argues that the habit of adult playing companies to duplicate the successful offerings of their competitors with similar offerings of their own was "a regular feature of competition among the professional companies" (4). She also raises a question about the title of ''Wise Man'': namely, if the Admiral's players had Munday's play in repertory, why did Henslowe ignore the popularity of John a Kent as a folk figure by choosing a title that made the company's wise man anonymous? (5). For John a Kent as a folk hero, see Ashton, "Jack a Kent"; and Collier, ''John a Kent'' (xxii-xxv). | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

===Date=== | ===Date=== | ||

The date of ''The Wise Man of West Chester'' is not in dispute; however, the date of the manuscript of ''John a Kent'' has been read as 1590, 1595, and 1596. All scholars who address the issue of date agree that it is the manuscript only, not the play itself, to which the date applies. | |||

'''Shapiro''' briefly cooled speculation on the link between the two plays by rereading the date | :'''Fleay''' gave the date of Munday's manuscript as 1595, emphasizing that the date was not necessarily "the date of production". '''Greg''' initially accepted that date but subsequently decided that "it is quite certainly ' … Decembris 1596'" ("Autograph," 89). | ||

<br> | |||

:'''Shapiro''' briefly cooled speculation on the link between the two plays by rereading the date on the manuscript of ''John a Kent'' as 1590. This date gladdened the hearts of those intent on a competition among such magician plays ''c''. 1590 as ''Doctor Faustus'' and ''Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay'', but it necessarily loosened the relationship of the Munday manuscript as in some way current with the debut of ''The Wise Man of West Chester'' on the stage at the Rose. | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

{| cellpadding="5" border="0" class="wikitable" | {| cellpadding="5" border="0" class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 200: | Line 202: | ||

|} | |} | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

'''Ioppolo''' has | :'''Ioppolo''' recently has stated that the Munday date is "1595" (101). '''Gurr''' cites Ioppolo on the date (''Shakespeare's Opposites'', 106). | ||

<br> | |||

:'''Jackson''' (as Shapiro, above) is primarily interested in the date of Munday's manuscript because of its implications for the date of ''Sir Thomas More''. He reviews the dating history of ''John a Kent'' and reverts to "the old ''terminus ad quem'' of December 1596" ([http://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/15-3/jackdate.htm ¶8]). Relatively indifferent to the relationship of ''Wise Man'' and Munday's play, Jackson considers it "possible ... that the Admiral's Men's play was merely influenced in some way by ''John a Kent'' or vice versa" ([http://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/15-3/jackdate.htm ¶9]). | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

===Company Commerce=== | ===Company Commerce=== | ||

Various scholars have used the identification of ''Wise Man'' as a way to discuss commercial aspects of the theatrical marketplace. | |||

:'''Ashton''' saw ''John a Kent'' as separate from ''Wise Man'' at least in part because he believed Munday's play belonged in the repertory of Shakespeare's Shakespeare's company (which he called "Strange's Company"): "Munday was ... an experienced man of the theater [; and possibly in 1594] he was engaged to write for Strange's Company and … his first effort for them was ''John a Kent'', designed to compete with one of the most popular plays [i.e, ''Wise Man''] being presented by the companies under Henslowe's management" ("Date," 230). | |||

<br> | |||

:'''Gurr''', seeing ''Wise Man'' and ''John a Kent'' as the same play, defines the personality of the Admiral's players by their "disguise" plays at the Rose in 1594 and following. He argues that an early exemplar of that disguise dramaturgy was ''Wise Man'' a.k.a. ''John a Kent''. | |||

<br> | |||

:'''Knutson''' sees ''Wise Man'' as an exemplar of the principle of repertorial competition through duplication within the repertory of the Admiral's players (3-4). She notes that in 1594 ''Wise Man'' shared the stage with the revival of Christopher Marlowe's ''Doctor Faustus''; and, perhaps by coincidence but perhaps also by a marketing strategy of duplicating one's successful offerings, the Admiral's players purchased ''Wise Man'' in advance of a revival of Marlowe's play. She sees an additional parallel in the property of a wooden leg, which the text of ''Doctor Faustus'' requires in both its A and B versions (7-8). Acknowledging the lengthy and financially successful run of ''Wise Man'', she observes that the play demonstrates that "journeyman plays of the period were outstanding commercial properties" (9). | |||

<br> | |||

: | |||

:'''Syme''', taking ''Wise Man'' at face value as a discrete play, refers to it often in his argument that plays not by Marlowe, Peele, or Kyd were the bread-and-butter of commerce at the Rose. He uses the play also to challenge popular scholarly assumptions that the most popular plays in a company's repertory were likely to be published. | :'''Syme''', taking ''Wise Man'' at face value as a discrete play, refers to it often in his argument that plays not by Marlowe, Peele, or Kyd were the bread-and-butter of commerce at the Rose. He uses the play also to challenge popular scholarly assumptions that the most popular plays in a company's repertory were likely to be published. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

==For What It's Worth== | ==For What It's Worth== | ||

Greg thought that the existence of "Kentes woden leage" in the inventory taken by Henslowe in March 1598 (Foakes, 320) reinforced the argument that ''Wise Man'' was ''John a Kent'' masquerading under another title (II.172). He solved the problem of there not being a need for such a wooden leg in the Munday manuscript by suggesting the latter was a revision that edited out the episode with the leg. Other than the assumption that the "wise man" of ''Wise Man'' must be in some sense "Kent," there is nothing to link that property with the anonymous play. | Greg thought that the existence of "Kentes woden leage" in the inventory taken by Henslowe in March 1598 (Foakes, 320) reinforced the argument that ''Wise Man'' was ''John a Kent'' masquerading under another title (II.172). He solved the problem of there not being a need for such a wooden leg in the Munday manuscript by suggesting the latter was a revision that edited out the episode with the leg. Other than the assumption that the "wise man" of ''Wise Man'' must be in some sense "Kent," there is nothing to link that property with the anonymous play. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[[category:all]][[category:Admiral's]][[category:Henslowe's records]] | [[category:all]][[category:Admiral's]][[category:Henslowe's records]] | ||

| Line 228: | Line 229: | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Ashton, J. W. "The Date of ''John A Kent and John A Cumber''." ''Philological Quarterly'' 8.3 (1929): 225-32.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Ashton, J. W. "The Date of ''John A Kent and John A Cumber''." ''Philological Quarterly'' 8.3 (1929): 225-32.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — —. "Jack A. Kent: The Evolution of a Folk Figure." ''The Journal of American Folklore'' 47.186 (1933):362-68.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — —. "Jack A. Kent: The Evolution of a Folk Figure." ''The Journal of American Folklore'' 47.186 (1933): 362-68.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Collier, John Payne, ed. ''The Diary of Philip Henslowe, from 1591 to 1609''. London: Shakespeare Society, 1845.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Collier, John Payne, ed. ''The Diary of Philip Henslowe, from 1591 to 1609''. London: Shakespeare Society, 1845.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — —, ed. ''John a Kent and John a Cumber; A Comedy, By Anthony Munday''. London: Shakespeare Society, 1851.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — —, ed. ''John a Kent and John a Cumber; A Comedy, By Anthony Munday''. London: Shakespeare Society, 1851.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Greg, W. W. "Autograph Plays by Anthony Munday." ''The Modern Language Review'' 8.1 (1913): 89-90.</div> | |||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Gurr, Andrew. ''Playgoing in Shakespeare's London''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Gurr, Andrew. ''Playgoing in Shakespeare's London''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — — | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">— — —. ''Shakespeare's Opposites: The Admiral's Company 1594-1625''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Ioppolo, Grace. ''Dramatists and their Manuscripts in the Age of Shakespeare, Jonson, Middleton and Heywood: Authorship, Authority and the Playhouse''. New York: Routledge, 2006.</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Ioppolo, Grace. ''Dramatists and their Manuscripts in the Age of Shakespeare, Jonson, Middleton and Heywood: Authorship, Authority and the Playhouse''. New York: Routledge, 2006.</div> | ||

<div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Jackson, MacDonald P. "Deciphering a Date and Determining a Date: Anthony Munday's ''John a Kent and John a Cumber'' and the Original Version of ''Sir Thomas More''." ''Early Modern Literary Studies'' 15.3 (2011). [http://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/15-3/jackdate.htm ''EMLS'']</div> | <div style="padding-left: 2em; text-indent: -2em">Jackson, MacDonald P. "Deciphering a Date and Determining a Date: Anthony Munday's ''John a Kent and John a Cumber'' and the Original Version of ''Sir Thomas More''." ''Early Modern Literary Studies'' 15.3 (2011). [http://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/15-3/jackdate.htm ''EMLS'']</div> | ||

| Line 243: | Line 245: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[[category:Martin Slater]] | [[category:Martin Slater]][[category:''Sir Thomas More'']][[category:folk characters]][[category:Folger]][[category:Huntington]] | ||

Site created and maintained by [[Roslyn L. Knutson]], Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated | Site created and maintained by [[Roslyn L. Knutson]], Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated 3 February 2012. | ||

Revision as of 16:48, 3 February 2012

Historical Records

Henslowe's Diary

F.10v (Greg I.20)

| ye 2 of desember 1594 | ................ | ne | ..... | Rd at the wise man of chester | ................ | xxxiijs |

| ye 6 of desember 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at wiseman of weschester | ................ | xxxiiijs |

F. 11 (Greg I.21)

| ye 29 of desember 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wissman of weschester | ................ | iijli ijs |

| ye 16 of Jenewarye 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wiseman of weaschester | ................ | iijli |

| ye 23 of Jenewary 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wiseman of wescheaster | ................ | iijli vjs |

| ye 4 of febreary 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wysman of weschester | ................ | iijli iiijs |

| ye 12 of febreary 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at wisman of weschester | ................ | liijs |

F.11v (Greg I.22)

| ye 19 of febrey 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at wisman of weschester | ................ | xxxxvjs |

| ye 28 of febreary 1594 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman of weschester | ................ | xxxixs |

| ye 25 of Aprrell 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wissman | ................ | xxxixs |

| ye 26 of Aprrell 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisseman of weschester | ................ | iijli |

| ye 6 of may 1596 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at wiseman | ................ | xxxxs |

| ye 15 of may 1596 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at wisse man of weschester | ................ | xxxxiiijs |

F.12v (Greg I.24)

| ye 26 of maye 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at weschester | ................ | xxxjs |

| ye 4 of June 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman of weschester | ................ | xxijs |

| ye 11 of June 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wissman of weschester | ................ | xxxxvijs |

| ye 26 of aguste 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman of wescheaster | ................ | xxxixs |

| ye 9 of septmber 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wise man | ................ | xxxxiiijs |

F.13 (Greg I.25)

| ye 29 of septmber 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wiseman | ................ | xvs |

| ye 6 of october 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman | ................ | xvijs |

| ye 19 of october 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman | ................ | xvijs |

| — mr pd— | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at weschester | ................ | xxs |

F.14 (Greg I.27)

| ye 29 of desember 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman of weschester | ................ | xxijs |

| ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wissman of weschester | ................ | xviijs |

F.14v (Greg I.28)

| ye 4 of febreary 1595 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wissman of weschester | ................ | xxijs |

F.15v (Greg I.30)

| ye 17 of aprrell 1596 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman of weschester | ................ | xxxs |

| ye 30 of aprrell 1596 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at wisman | ................ | xs |

F.21v (Greg I.42)

| ye 8 of June 1596 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at the wisman of weschester | ................ | xxs |

| ye 7 of July 1596 | ................ | ..... | ..... | Rd at wisman of weschester | ................ | xvjs |

F.27 (Greg I.53)

| [July 1597] | ..... | 8 | .................... | tt at wismane of weschester | ............... | 01— | 00— | 01-00-03 |

F.27v (Greg I.54)

| [July 1597] | ..... | 12 | .................... | tt at wismane of weschester | ............... | 00— | 18— | 00-01-00 |

- (marginal note: "marten slather went for the company of my lord admeralles men the 18 of July 1597")

| [July 1597] | ..... | 18 | .................... | tt at wisman | ............... | 01— | 10— | 00-00-00 |

F.93v (Greg I.148)

- pd at the apoyntment of the 19 of septmber

- 1601 for the playe of the wysman of weschester

- vnto my sonne E Alleyn the some of ............... xxxxs

Theatrical Provenance

The Wise Man of West Chester was performed at the Rose playhouse by the Admiral's players beginning on 2 December 1594; its initial entry carries Philip Henslowe's enigmatic "ne." Its purchase in 1601 makes it second among the nine playbooks sold by Edward Alleyn to the company in the early years of the Fortune playhouse.

Probable Genre(s)

Magician play; Pseudo-History (Harbage)

Possible Narrative and Dramatic Sources or Analogues

None known.

References to the Play

None known.

Critical Commentary

The presiding critical question about The Wise Man of West Chester is whether its title is merely a variant of the extant John a Kent and John a Cumber by Anthony Munday. If so, Wise Man is not lost. Scholarly discussion of this question focuses on three issues: similar subject matter, dates, and commerce.

Similar Subject Matter

From the time Dulwich College put Henslowe's diary into the hands of scholars, theater historians have tried to match titles in Henslowe's records with extant plays on the basis of similar titles and/or subject matter. That not always has been the case with Wise Man. Malone, who first saw Henslowe's manuscript, did not identify Wise Man with John a Kent, but he probably did not know that John a Kent existed. Incidentally, Malone misread Henslowe's title as "the wise men of chester" (Malone, 3.304); subsequent editions of the diary by Collier, Greg, and Foakes have corrected the reading. Collier noted that Wise Man "was a new play" in his 1845 edition of the diary (Collier, 45), but he too probably did not know John a Kent then. However, in 1851 he published the first edition of John a Kent, exploring thoroughly its provenance, dramatist, and subject matter, yet he did not make a connection to Henslowe's Wise Man.

File:WisemanHD.png Henslowe's diary, f. 10v (Henslowe-Alleyn)

- Fleay appears to be the first to specify a link between the two plays in A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama, 1559-1642 (1891). He entered Wise Man in his list of anonymous plays, noting the purchase of its script by the Admiral's players on 19 September 1601 (Fleay, 2.303); for further commentary, he referred the reader to the entry for John a Kent and John a Cumber. In that entry, Fleay stated, "I have no doubt that it [John a Kent] is the same as The Wiseman of West Chester produced by the Admiral's men at the Rose 2nd Dec. 1594" (Fleay, 114). He gave no reason for his lack of doubt.

- Greg thought Fleay was "almost certainly right" in making the identification (Greg, II.172). Greg made the first plausible link between Wise Man and John a Kent by assigning an item in Henslowe's 1598 inventory, "Kentes woden leage," to Wise Man (presumably on the assumption that "West Chester" and/or "wise man" = "Kent"). Inconveniently for this thesis, the manuscript of John a Kent has no need for a wooden leg. Therefore Greg suggested that the manuscript might be a revision with the episode of the wooden leg edited out.

- Despite the authority of Fleay and Greg, opinion did not harden into fact. St. Clare Byrne, editor of the Malone Society Reprint of John a Kent and John a Cumber, acknowledged the scholarly interest in linking Munday's play with The Wise Man of West Chester as well as Randal Earl of Chester. She thought the relationship of the plays, through serial revision, was "by no means impossible" but saw "no secure basis for speculation" (x).

- Beginning in 1929, Ashton published a series of articles disputing the link between Wise Man and John A Kent. In the first of those, he asserted that "there is not a shred of evidence that John a Kent and the Wiseman are identical" (225). He granted the link of each play with magic and the landscape of West Chester, but noted the greater prominence in Munday's play of Welsh connections.

- Gurr is the leading supporter currently of Wise Man as John a Kent. At least since 1987 he has been renaming the Henslowe play The Wise Men of West Chester and indexing it accordingly (Playgoing in Shakespeare's London, 140, 152, and 307; see also Shakespeare's Opposites, 317). In Shakespeare's Opposities he offers a new argument that concerns the book-keeper (or scribe) commonly known as Hand C, whose hand appears in various notations including "prompt-directions" (St. Clare Byrne, vii). According to Gurr, Hand C "belonged" to the Admiral's company in the sense that he was "a loyal worker for Alleyn through more than a decade" (106, n.27). The apparent inference is that Hand C's hand confirms the Admiral's ownership of John a Kent and thereby strengthens the case that Wise Man and the Munday play are the same.

- Knutson argues for the discrete identity of Wise Man. She is primarily resisting the urge among scholars "on slender evidence or intuition" to identify plays with similar subjects or leading characters as the same or as versions of one another (3). She argues that the habit of adult playing companies to duplicate the successful offerings of their competitors with similar offerings of their own was "a regular feature of competition among the professional companies" (4). She also raises a question about the title of Wise Man: namely, if the Admiral's players had Munday's play in repertory, why did Henslowe ignore the popularity of John a Kent as a folk figure by choosing a title that made the company's wise man anonymous? (5). For John a Kent as a folk hero, see Ashton, "Jack a Kent"; and Collier, John a Kent (xxii-xxv).

Date

The date of The Wise Man of West Chester is not in dispute; however, the date of the manuscript of John a Kent has been read as 1590, 1595, and 1596. All scholars who address the issue of date agree that it is the manuscript only, not the play itself, to which the date applies.

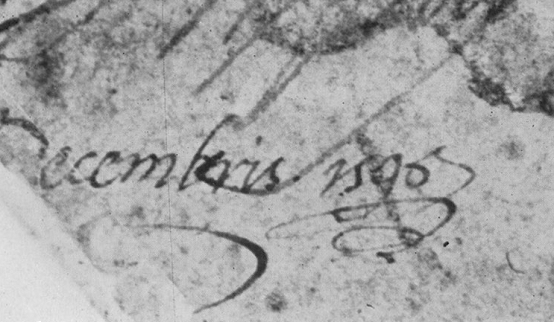

- Fleay gave the date of Munday's manuscript as 1595, emphasizing that the date was not necessarily "the date of production". Greg initially accepted that date but subsequently decided that "it is quite certainly ' … Decembris 1596'" ("Autograph," 89).

- Shapiro briefly cooled speculation on the link between the two plays by rereading the date on the manuscript of John a Kent as 1590. This date gladdened the hearts of those intent on a competition among such magician plays c. 1590 as Doctor Faustus and Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, but it necessarily loosened the relationship of the Munday manuscript as in some way current with the debut of The Wise Man of West Chester on the stage at the Rose.

The date on the manuscript of John a Kent ((Fig. 1, Jackson))

- Ioppolo recently has stated that the Munday date is "1595" (101). Gurr cites Ioppolo on the date (Shakespeare's Opposites, 106).

- Jackson (as Shapiro, above) is primarily interested in the date of Munday's manuscript because of its implications for the date of Sir Thomas More. He reviews the dating history of John a Kent and reverts to "the old terminus ad quem of December 1596" (¶8). Relatively indifferent to the relationship of Wise Man and Munday's play, Jackson considers it "possible ... that the Admiral's Men's play was merely influenced in some way by John a Kent or vice versa" (¶9).

Company Commerce

Various scholars have used the identification of Wise Man as a way to discuss commercial aspects of the theatrical marketplace.

- Ashton saw John a Kent as separate from Wise Man at least in part because he believed Munday's play belonged in the repertory of Shakespeare's Shakespeare's company (which he called "Strange's Company"): "Munday was ... an experienced man of the theater [; and possibly in 1594] he was engaged to write for Strange's Company and … his first effort for them was John a Kent, designed to compete with one of the most popular plays [i.e, Wise Man] being presented by the companies under Henslowe's management" ("Date," 230).

- Gurr, seeing Wise Man and John a Kent as the same play, defines the personality of the Admiral's players by their "disguise" plays at the Rose in 1594 and following. He argues that an early exemplar of that disguise dramaturgy was Wise Man a.k.a. John a Kent.

- Knutson sees Wise Man as an exemplar of the principle of repertorial competition through duplication within the repertory of the Admiral's players (3-4). She notes that in 1594 Wise Man shared the stage with the revival of Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus; and, perhaps by coincidence but perhaps also by a marketing strategy of duplicating one's successful offerings, the Admiral's players purchased Wise Man in advance of a revival of Marlowe's play. She sees an additional parallel in the property of a wooden leg, which the text of Doctor Faustus requires in both its A and B versions (7-8). Acknowledging the lengthy and financially successful run of Wise Man, she observes that the play demonstrates that "journeyman plays of the period were outstanding commercial properties" (9).

- Syme, taking Wise Man at face value as a discrete play, refers to it often in his argument that plays not by Marlowe, Peele, or Kyd were the bread-and-butter of commerce at the Rose. He uses the play also to challenge popular scholarly assumptions that the most popular plays in a company's repertory were likely to be published.

For What It's Worth

Greg thought that the existence of "Kentes woden leage" in the inventory taken by Henslowe in March 1598 (Foakes, 320) reinforced the argument that Wise Man was John a Kent masquerading under another title (II.172). He solved the problem of there not being a need for such a wooden leg in the Munday manuscript by suggesting the latter was a revision that edited out the episode with the leg. Other than the assumption that the "wise man" of Wise Man must be in some sense "Kent," there is nothing to link that property with the anonymous play.

Works Cited

Site created and maintained by Roslyn L. Knutson, Professor Emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock; updated 3 February 2012.